The AfCFTA and Africa’s fresh produce trade

For many years, the African continent’s leaders have been locked in political discussions surrounding the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). AfCFTA is an ambitious trade pact to form the world’s largest free trade area by creating a single market for goods and services for almost 1.3bn people across Africa, thereby deepening Africa’s economic integration. The trade area could have a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of around US$3.4trn, but achieving its full potential depends on significant policy reforms and trade facilitation measures across African signatory nations. Furthermore, the implementation of the flagship project has been slowed down by the global repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war on Ukraine and persistent armed insurgencies across the continent. Nonetheless, the AfCFTA aims to reduce tariffs among member states and covers policy areas such as trade facilitation and services, as well as regulatory measures such as sanitary standards and technical barriers to trade. The agreement was initially brokered by the African Union (AU) and was signed by 44 of its 55 member states in Kigali, Rwanda, on 21 March 2018. The only country that has still not signed the agreement is Eritrea, which has a largely closed economy.

Why does African agricultural trade need the AfCFTA?

Trade integration across Africa has long been limited by outdated border and transport infrastructure, further exacerbated by a patchwork of differing regulations across dozens of markets. Furthermore, governments have often erected trade barriers to defend their markets from the regional competition, making it more expensive for countries to trade with near neighbours than countries much further afield.

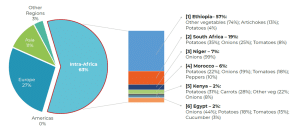

By definition, the fresh produce cluster consists of fruit, vegetables and flowers. Africa’s share of the global fresh produce trade is 6%, with Africa’s fresh produce exports following a similar pattern as the rest of the world, i.e., fruit-dominated. Vegetables are traded more within the continent, whilst flower exports are low compared to fruit and vegetables. More than 60% of Africa’s fresh produce exports are destined for Europe and Asia. The European Union (EU) is the primary market for African fresh produce, with the Netherlands being the leading importer accounting for 14% of total imports.

In comparison, sources of African fresh produce imports are diversified relative to markets. North America and Europe are the leading regional suppliers of fresh produce to the African continent. Nonetheless, Africa was a net exporter of fresh produce over the past five years. If we consider the biggest importing markets into Africa, 35% is derived from intra-African trade when it comes to fresh fruit imports. Regarding fresh vegetable imports, a whopping 63% comes from intra-African trade, with South Africa (SA) being a prominent player in the fruit and vegetable import trade.

Figure 1: Fresh fruit imports in Africa – average value 2017-2021: US$624mn

Source: Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP)

Figure 2: Fresh vegetable imports in Africa – average value 2017-2021: US$955mn

Source: BFAP

Comments:

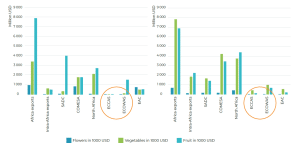

Despite these already prominent levels of intra-Africa trade in the fresh produce market, high import duties and non-tariff measures (NTMs) remain significant barriers to intra-Africa trade. Thus, reducing tariffs and NTMs can unlock further trade opportunities in a market ripe with opportunity. Regional trade blocks in the north and south of the African continent dominate the current fresh produce trade. However, there are pockets of potential in other regions.

Figure 3: Intra-regional fresh produce trade, Africa fresh produce exports (Lhs) and imports (Rhs)

Source: BFAP

What are the predicted economic benefits of the AfCFTA?

The economic benefits of the AfCFTA extend far beyond the fresh produce trade and Africa’s agricultural sector. A 2020 World Bank report estimated that by 2035, real income gains from full implementation of the agreement could be 7%, or nearly US$450bn. By 2035, the volume of total exports will increase by almost 29% relative to business as usual. Intra-continental exports would increase by more than 81%, while exports to non-African countries would rise by 19%. The World Bank further predicts that the agreement could contribute to lifting an additional 30mn people out of extreme poverty and 68mn people from moderate poverty.

Yet the impact across countries will not be uniform. The World Bank says that at the very high end, countries like Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe could see income gains p.a. of 14% each. At the low end, some countries (such as Madagascar, Malawi, and Mozambique) would see real income gains of only around 2% p.a. In a follow-up report published in June 2022, the Bank listed benefits from the increase of foreign direct investment (FDI) expected to accrue from the agreement.

- Under an “AfCFTA FDI broad scenario”, it predicts that Africa may record an increase of 111% in FDI by 2035, further boosting real income gains in Africa to about 8% in 2035.

- Under an “AfCFTA FDI deep scenario”, it examines the additional gains that could result from expanding the agreement from trade in goods and services to harmonising policies on investment, competition, e-commerce, and intellectual property rights. Under this scenario, it predicts an increase in FDI of 159% by 2035 and income gains of up to 9% by 2035.

Other potential benefits of the AfCFTA highlighted by the June 2022 report include the following:

- Higher-paid, better-quality jobs, with women seeing the most significant wage gains.

- Wage increases of 11.2% for women and 9.8% for men by 2035, albeit with regional variations depending on the industries that expand the most in specific countries.

- Under deep integration, a 32% rise in Africa’s exports to the rest of the world by 2035, while intra-African exports would grow by 109%, led by manufactured goods.

In its Economic Development in Africa Report 2021, the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) said that “the total untapped export potential of intra-African trade is around US$21.9bn, equivalent to 43% of intra-African exports”. Furthermore, more than one-third of that export potential is explained by frictions, namely, static untapped export potential, which implies that US$8.6bn in trade could be realised by engaging actively in efforts to identify and address market frictions currently present in African trade.

How will the AfCFTA work with existing regional trade areas?

According to an analysis by the World Bank, in the policy areas already covered by subregional preferential trade areas (PTAs), such as the Common Market for East and South Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the South African Development Community (SADC), the AfCFTA will offer a common regulatory framework, reducing market fragmentation created by different sets of rules. Second, the AfCFTA will be an opportunity to regulate policy areas important for economic integration that are often regulated in trade agreements but have not been covered in most of Africa’s PTAs, which the Bank says “tend to be shallow”.

Challenges to the success of the AfCFTA

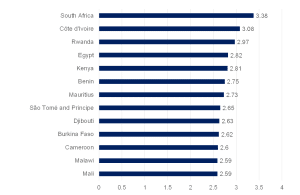

There are many challenges currently present across the continent that could dampen the overall success of the AfCFTA. The chief and foremost relate to the generally poor logistical infrastructure across the continent. The Logistical Performance Index (LPI), developed by the World Bank, represents a measure of the efficiency of the customs clearance process, quality of trade- and transport-related infrastructure, ease of arranging competitively priced shipments, quality of logistics services, ability to track and trace consignments, and frequency. The LPI uses a scale of 1-5, and in 2018 only three African countries scored above the global average of 2.87.

Figure 4: Top African countries on the LPI scale

Source: World Bank, Anchor Capital

Final Commentary:

Furthermore, demand for fresh produce is sensitive to income, i.e., high-income groups account for a large consumption share for most fruits. Thus, the agreement’s implementation must be accompanied by economic growth, increased incomes, and socio-economic upliftment to meet its objectives. These conditions apply to fresh produce trade, as two-thirds of African countries are considered least developed countries (LDCs). As such, economic growth and opportunity for further urbanisation increase the potential for more fresh produce demand.

Overall, the AfCFTA was signed with the primary objective of increasing intra-Africa trade beyond the scope of the fresh produce trade. Whilst the African continent has made progress since establishing the AfCFTA, the agreement still needs to be implemented, most likely in the same way as the EU trade agreements, but with more ambition and a longer-term vision. For the African continent to make the most of the opportunity the AfCFTA provides, NTMs and other trade barriers must be reduced substantially, with economic growth and rising incomes at the centre of unlocking opportunities as key determinants of trade. Furthermore, investment in logistics and infrastructure is critical to capitalise on Africa’s trade potential, particularly regarding the perishability characteristics of the fresh produce trade.

Read more about South Africa’s agricultural conditions here.

At Anchor, our clients come first. Our dedicated Anchor team of investment professionals are experts in devising investment strategies and generating financial wealth for our clients by offering a broad range of local and global investment solutions and structures to build your financial portfolio. These investment solutions also include asset management, access to hedge funds, personal share portfolios, unit trusts, and pension fund products. In addition, our skillset provides our clients with access to various local and global investment solutions. Please provide your contact details here, and one of our trusted financial advisors will contact you.