Inflation is certainly the topic du jour for global investors with the most recent US inflation data doing nothing to assuage investor concerns as October’s headline inflation print of 6.2% YoY was the largest jump in US prices since November 1990. In this note, we look at the current elevated level of inflation and the possible impact of this on global bond returns.

In terms of the impact of inflation on developed market (DM) bonds, most DM bonds are fixed-rate bonds (i.e., the coupon income they pay is set at the issuance of the bond), which means that higher inflation tends to impact these bonds in the following ways:

- As the inflation rate increases, the real (above-inflation) income that investors will earn to maturity on these bonds shrink and the capital value that is returned at maturity will also be worth less in real terms.

- If central banks perceive the higher inflation to be systemic or persistent then they potentially need to respond by raising their policy rates faster and/or higher than expected. As policy rates increase faster/higher than expected, the attractiveness of the fixed coupons on existing bonds decreases relative to prospective future income possibilities.

- Investors will respond to the prospect of relatively less attractive income on fixed-rate bonds already in issue by selling these bonds, driving the price down and causing capital losses for existing investors in those bonds. As the price of these fixed-rate bonds drop, the coupons become relatively more attractive (i.e., yields go higher), improving the real yields and the relative attractiveness of the fixed coupons.

In a perfect world, the yield on a bond would reflect the market’s best estimate of the average rates from now until the bond’s maturity. However, in practice the supply/demand mismatch also plays a role so, for example, quantitative easing ([QE] or where a country’s central bank buys bonds to increase the money supply) will add a source of demand that is completely insensitive to price. At the current quantum of global QE, that is enough to overwhelm any fundamental value for bonds, based on future expected rates. Heightened investor anxiety also typically increases the demand for perceived safe assets such as DM bonds, another example of a potential source of valuation-insensitive demand. Changes in the supply of bonds also need to be considered. As governments reduce the amount of fiscal support they provide to economies with the pandemic effects fading, they will issue relatively fewer bonds as their funding requirements reduce. So, in addition to forecasts on the future path of inflation and central bank rates, bond investors must also consider future supply/demand imbalances.

We note that global DM yields tend to be somewhat interlinked because DM currency pairs are not particularly volatile, so if US bond yields get significantly higher than e.g., euro bond yields, investors will shift their assets out of euro-denominated bonds and into US dollar-denominated bonds to benefit from the additional yield pickup. This will, in turn, restore some global equilibrium (i.e., euro yields will rise, and US dollar yields will fall). So, we need to consider US inflation, central bank activity, and supply/demand imbalances, as well as those forces in other DMs.

While inflation is fundamental to the value of bonds, it is not necessarily as simple as saying that higher US inflation will result in capital losses for bonds. We must also consider higher US inflation in the context of all the other factors discussed above. Below we provide our view on some of those factors:

- While we think the period of “transitory” higher inflation could linger longer than is comfortable, we do not believe US inflation will remain persistently high over a multi-year period for many reasons, including the following:

- Supply chains will respond to bottlenecks with efficiency improvements, which will, in turn, make it cheaper to move goods around the globe in the future (and will be deflationary longer term).

- Historical structural shifts in consumption trends in DMs away from spending on goods and towards spending on services will resume once the effects of the pandemic fade, thus providing a headwind to the current, above-average demand for goods (which will also be deflationary over the longer term).

- Technology is a deflationary force, and the pace of technological innovation is, if anything, accelerating (this will again be deflationary over the longer term).

- Demographic trends in the world’s biggest consumer economies (Europe, Japan, China, and the US) are bad for consumption growth (fertility rates are declining and thereby placing pressure on population growth, which has been a major tailwind for consumption historically i.e., more consumers=more consumption). This will also be a deflationary factor longer term.

- Deflationary forces in Europe and Japan, in particular, should assist in keeping those regions’ rates anchored close to 0%, thus acting as a drag on the potential for US rates to drift significantly higher.

- QE has become a permanent aspect of DM monetary policy as we saw in late 2019 (before the impact of the pandemic), when the US Federal Reserve (Fed) was forced to reverse course on shrinking its balance sheet as market reaction showed how reliant normal market functioning had become on that type of monetary policy. Thus, we expect a degree of price-insensitive demand for bonds from QE to remain a meaningful factor going forward (not only in the US but particularly in Japan and Europe).

- Issuance of DM government bonds will slow (possibly by as much as 20% in the US) reducing the supply of DM bonds available to investors.

Having said all of the above, we note that it is not our base-case scenario that negative real yields will last indefinitely and we expect yields to drift higher over the course of the next 12 months. Basically, in our view, we should see inflation and rates move towards each other (with inflation doing most of the work!). In practice, what this means is that US 10-year government bond yields are at about 1.6% currently. However, if we see these 10-year rates drifting towards 1.9%, that 0.3% move higher in yield will have the following impact on an illustrative bond investment:

A 0.3% [change in rates] x 9.3 years [duration of the current US 10Y government bond] = a 2.8% capital loss.

Capital losses occur in direct proportion to the interest rate move, so in our example of a 0.3% rise in rates resulting in a 2.8% capital loss, if that 0.3% rate rise happens in one week, the capital loss will also happen in one week. While the aforementioned calculation is a good rule of thumb when determining the extent of capital losses (or gains) on a bond, there are many factors impacting the degree of capital loss (or gain) a bond investor could experience. Corporate bonds (which generally have higher yields because of an embedded credit spread) will have a relatively lower duration, making them slightly less sensitive to interest rate movements, as will bonds with shorter maturities. Bonds with embedded optionality allowing the issuer to redeem them earlier will also behave slightly differently. The changing shape of the yield curve (i.e., if short-term yields change at a different quantum relative to longer-term yields) also impacts bonds differently.

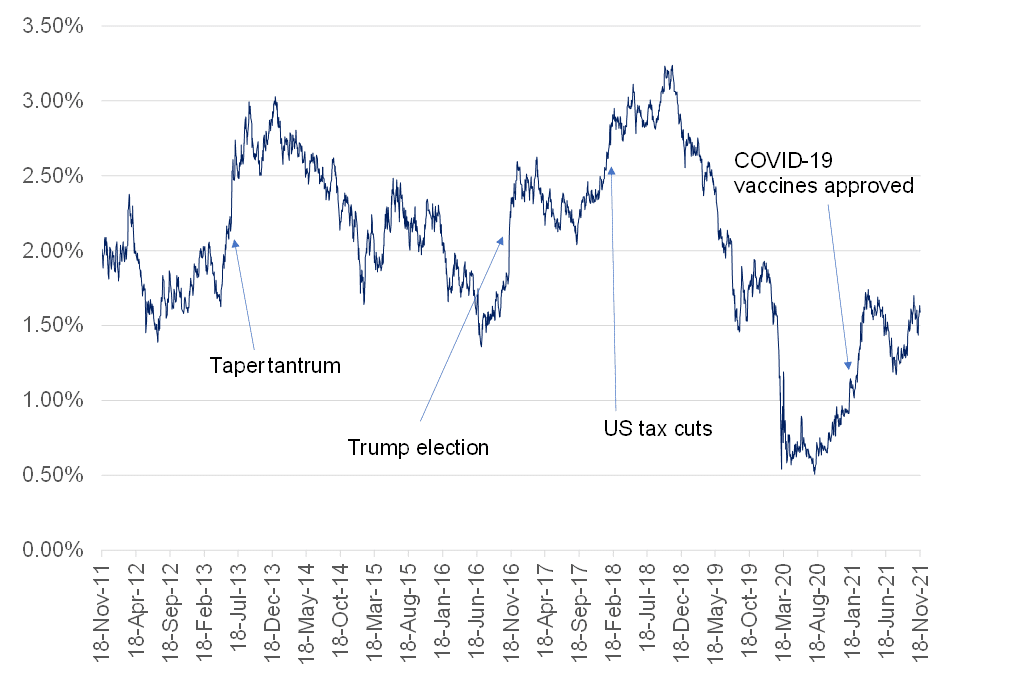

It is not our base case that we will see yields move higher in a very short period of time, but yield moves, particularly in long-dated yields, often happen in jumps around significant events rather than gradually. Some of the significant events that we have seen over the past decade or so that have resulted in big jumps in US long-term yields include:

- The 2013 taper tantrum.

- The surprise election of Donald Trump as US president in November 2016.

- 2018’s US tax cuts announcement.

- Earlier this year when it became clear that COVID-19 vaccinations were effective in reducing infections, thereby resulting in a normalising of US mobility.

Figure 1: US 10-year bond yields tend to re-price in sharp jumps around significant, unexpected events

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

As investors, the dilemma we have now is that the opportunity cost of waiting in cash, for fear of potentially experiencing capital losses in bonds as yields drift higher, is high, with investors earning no yield on US dollar cash. The longer you sit in cash the more income you forgo trying to avoid potential capital losses. Investors should rather consider structuring their asset allocation in a way that allows them the possibility of earning an inflation-beating return by combining investments that will deliver them the income and capital security they need (like bonds), but with an allocation to assets that will benefit from higher rates (e.g., US bank earnings tend to benefit from higher rates). An experienced financial advisor or investment manager can also structure a global fixed income portfolio in a way that reduces its vulnerability to inflation surprises.