South Africa’s current state

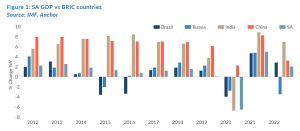

No one will disagree that SA currently finds itself in a deep state of internal economic lethargy as a country. Over the last decade, the economy has only grown by a mere 1% average, significantly lower than the 3.4% average of its BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China) counterparts. Moreover, for 2023, SA’s economic growth is expected to slow to below a meagre 1% as it continues to face a growing number of domestic headwinds. Notwithstanding the various global crises that manifested over the last few years or so, SA’s failure to advance its growth prospects despite the country’s diversified economic structure, deep financial markets, cutting-edge business capability and strength of institutions speaks to the inherent structural weakness present – in turn manifesting in chronically high levels of inequality and persistent unemployment.

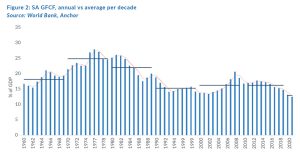

As a result, investment in SA’s economy is unsurprisingly faltering, with gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) dropping well short of the aspirational ratio of 30% of GDP set out in the National Development Plan of 2009 (SA’s key economic policy directive). A historic low of 13% of GDP was recorded in 2021 – as illustrated by Figure 2 below. Whilst the steady decline in GFCF can be partly ascribed to a minimal savings rate across the general SA populace, it can also be attributed to diminishing levels of expected return. This, in turn, adversely affects investment considerations for both local and international corporates. If a country’s investment climate (matched with its policy environment and economic conditions) is perceived to be overly restrictive, then future returns are called into question, hobbling expansion or new investment. Capital outlays are therefore driven by survival rather than a fundamental belief in growth opportunities, as has been the case for the past two years, thereby limiting the overall contribution of GFCF to the expenditure side of the local economy. For the economy to attract significant new investment (be it by domestic or offshore firms), the country will need to address, among others, electricity supply, transportation, and ports. Intuitively, if the cost of doing business is reduced, then investment and growth will follow.

The Cost of the failing infrastructure

However, calculating the economic cost of SA’s failing infrastructure (let alone trying to address it sustainably) is no easy task – particularly regarding the current electricity crisis and our failing rail infrastructure. Conventional wisdom states that ‘loadshedding is destroying the economy,’ but how much is it genuinely costing? Is it even possible to put a number on it? Depending on which methodology or numerical inputs you consider, the cost of the rolling blackouts in 2022 ranges anywhere from R70bn (Eskom’s estimates) to R560bn (The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research [CSIR] estimates). Factoring in all the secondary effects of loadshedding, the actual number is more than R3trn. While the ‘raw cost’ of loadshedding is naturally high due to the direct interruption of production etc., its multiplier effect across the greater economy is devastating, and its secondary effects are difficult to quantify. To calculate the true cost of SA’s chronic power failures over the past 15 years or so, one must consider the following:

- The many local businesses that have failed and closed, resulting in lost jobs.

- Families made destitute as a result of said business closures.

- The rising cost of managing and restoring the national power supply.

- Loss of investor, local consumer and business confidence.

- The loss of valuable skills to the economy as emigration rises due to a lack of confidence, which, in turn, has long-term detrimental effects on entrepreneurship, job creation and investment flows.

- The downgrading of SA from an investment grade sovereign risk rating to junk status by leading credit rating agencies due to the power crisis and various other policy failures.

- The loss of confidence in government and various institutional structures and the stress that, in turn, is placed on the socio-political environment and greater democratic disposition of the country.

This list is by no means exhaustive. There are plenty of other secondary effects to consider. What the above points do illustrate, however, is that arriving at the actual numerical cost of SA’s energy crisis is nearly impossible. Whilst the energy crisis is the current overwhelming constraint to economic activity in SA, similar concerns are also being expressed over rails, ports, and water. SA’s failing rail infrastructure poses particularly unique challenges in itself, which are exacerbated by the rail industry’s intrinsic ties to the energy supply sector. The local rail network covers over 30,000km, including two of the world’s premier heavy-haul lines – the Sishen-Saldanha Iron Ore Export line with an annual nameplate capacity of 60mn tonnes p.a. (MTPA), as well as the North Corridor (also known as the Coal Line) to Richards Bay with a nameplate capacity of 81 MTPA.

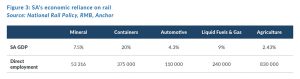

In recent years, Transnet, and its major subsidiary and freight rail operator, Transnet Freight Rail (TFR), have been subject to orchestrated corruption, which has impeded the state-owned enterprises’ (SOEs) ability to perform their commercial undertakings. Furthermore, the ability to execute a turnaround in the entity is increasingly undermined by the decision-makers within the entity itself and greater government. Further compounding the issue are poor operating standards, inefficient service delivery, a deterioration in the quality of infrastructure (due to theft, vandalism, and an inadequate maintenance regime), and recalled rolling stock contracts with international locomotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) resulting in the inability of the SOE to receive spares for its increasingly idle locomotive fleet. This has resulted in a large number of Transnet’s 1,900 locomotives being left standing. Overall, this has resulted in Transnet’s performance on some of its key strategic lines (such as the Richards Bay Coal Terminal) declining by 50% throughput to an estimated 43 MTPA in the current financial year (Figure 3) at the expense of the customers and economy that rely on these rail services to get SA’s output to international markets. The figure allocated to this decline solely on the Coal Export line is R1bn per day for Transnet’s 2022/2023 financial year.

This decline is felt across many sectors within SA’s greater economy, such as grain, where more grain is currently moved via conveyor belt than rail network. As a result of poor service levels from Transnet over the years, the industries that were fortunate enough to move their freight to road transport have done so. The only sectors left that utilise SA’s rail network are those that do not have a choice due to the nature of the payload and volume (i.e., mining, timber, bulk liquids, automotive manufacturers etc.). Ironically, these industries are some of the country’s biggest employers and economic contributors (such as Ford South Africa, which makes up 1.5% of SA’s GDP). As such, one cannot underestimate or disregard the importance of the rail industry to the SA economy, particularly in these current times of economic lethargy. As indicated by Figure 3 below, roughly 44% of SA’s GDP directly relies on rail. In turn, 1.6mn South Africans are directly employed by these industries with up to c. 7.3mn dependants.

The light at the end of the tunnel

However, it is not all doom and gloom. SA can pull itself out of its current economic inertia by sustainably addressing its failing infrastructure. Suppose one considers the current electricity crisis in particular. In that case, Vietnam offers a compelling case study of a country that is steadily enacting market reforms in a heavily state-led environment (much like SA), with the realisation that without a consistent energy supply, a country will never be able to sustainably meet the demands of a growing economy – something the SA government is only seemingly starting to realise. Vietnam has one of the most energy-intensive economies in the world. Since 2010, electricity consumption has increased by about 10% p.a. This is attributed to strong economic growth, increasing industrialisation, universal electrification, and modernisation. As a result, installed electrical capacity grew ten-fold, from 5GW in 2000 to 55GW in 2020, and Vietnamese citizens with access to electricity increased from 14% in 1993 to 99% in 2020.

Central to Vietnam’s steady progress in introducing legal and regulatory reforms to gradually open the electricity market to competition without adversely affecting supply (as is similarly required in SA) is a functional, vertically integrated, state-owned Vietnam Electricity (EVN) which is mildly profitable, and a political class (while not corruption-free) that understands the vast energy supply required to power the future growth of that country’s economy. The Vietnam government’s careful and considered approach is clearly working. Compare this to a country like the Dominican Republic, where far-reaching, market-orientated reform was enacted in an unsupportive political environment and a turbulent macroeconomic context that eventually led to the renationalisation of its power utilities.

At the end of the day, privatised utilities operate at higher levels of efficiency while adopting better governance and management practices. However, transitioning to that requires broad political agreement and careful and considered reforms – Vietnam demonstrates this. SA has the potential to follow a similar pathway to the likes of Vietnam in ensuring the security of energy supply while attaining the twenty-first-century climate change targets of weaning the energy sector off coal and other so-called “dirty” inputs. Such a transition to greener energy supplies represents the quickest path out of loadshedding and a once-in-a-generation opportunity to place SA on a high (and green) growth and development pathway.

The same can be said for challenges centred around SA’s failing rail infrastructure. The first signs of a turn in our rail industry will not be a change in the fortunes of a mining house on a different continent but rather the potential for job security in SA’s manufacturing sector with the further potential of SA’s export base. It will mean the decision of both local and international companies to invest in and expand their production facilities – it will mean market entrants rather than exits. The effect will be expansive across SA’s economy, which means investment and job creation. But a country’s economic prosperity is underpinned by firm confidence, rising levels of productivity and constructive physical and human capital investment. It is the foundation for SA to sustainably increase potential growth and narrow the income divide.

At Anchor, our clients come first. Our dedicated Anchor team of investment professionals are experts in devising investment strategies and generating financial wealth for our clients by offering a broad range of local and global investment solutions and structures to build your financial portfolio. These investment solutions also include asset management, access to hedge funds, personal share portfolios, unit trusts, and pension fund products. In addition, our skillset provides our clients with access to various local and global investment solutions. Please provide your contact details here, and one of our trusted financial advisors will contact you.