In this article, we examine the case for avoiding excessive concentration in US equities (not putting all your eggs in the US basket), thereby highlighting the risks of relying too heavily on a single market (over-concentration). We focus on three important considerations: current valuations, implied returns from those valuations, and prospective earnings growth rates. Together, these factors support a more diversified and measured allocation approach.

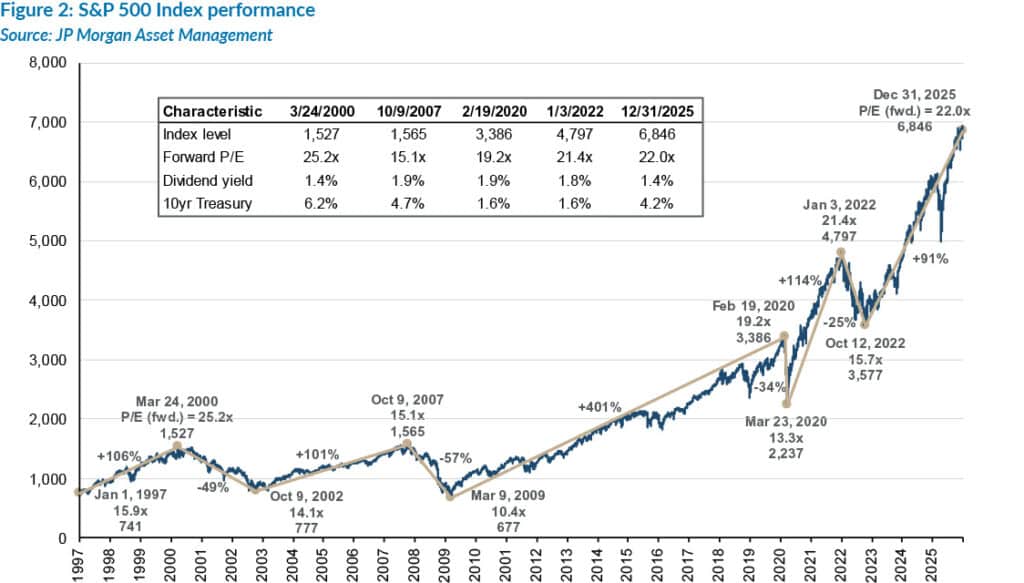

We begin with valuations. US equity market valuations are at historic highs. The S&P 500’s current forward price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple of c. 22x has only been this high on two other occasions in the past thirty years. Those were the late 1990s, as the dot-com bubble gathered steam, and the 2020-2021 COVID-19 bull market. As shown in Figure 2, both periods were followed by meaningful market corrections. From 2000 to 2002, the S&P 500 declined by 49% peak-to-trough, and the index fell by a much-faster 25% over just ten months in 2022.

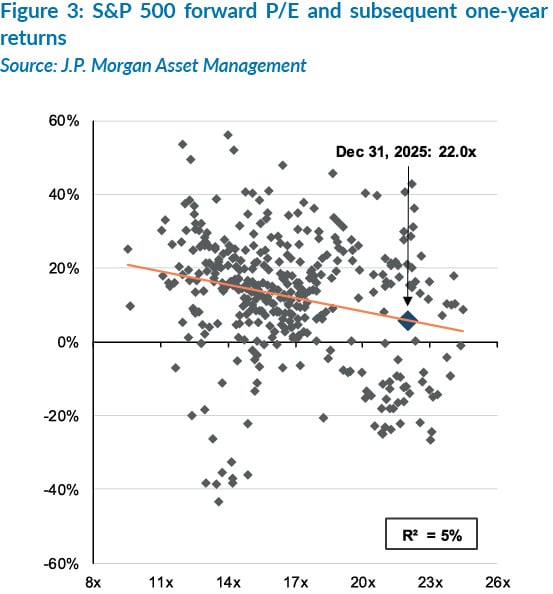

To be clear, high valuations are not reliable predictors of poor subsequent returns over the short term. As Figure 3 shows, subsequent one-year returns from similar valuation levels have ranged widely, from gains of c. 20% to losses of c. 40%. In other words, starting valuations, measured by the P/E multiple in this instance, offer little insight as an indicator of returns over the subsequent one year.

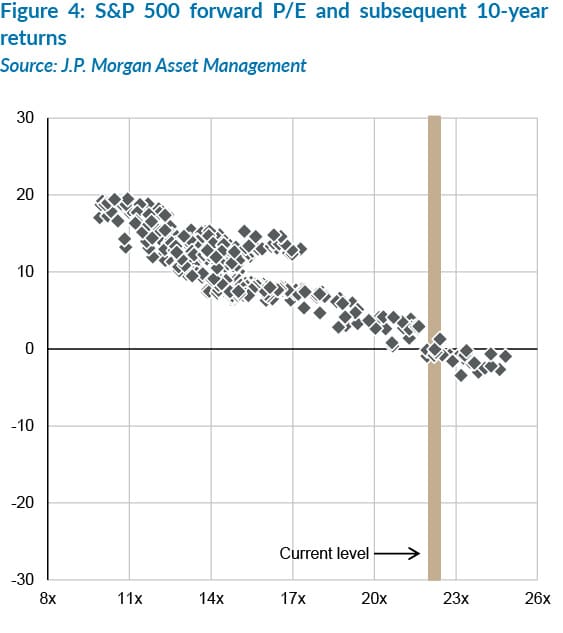

For ten-year subsequent returns, however, valuations become far more informative and are meaningfully more reliable predictors of subsequent returns. As illustrated in Figure 4, when forward P/E multiples have been at current levels in the past, subsequent S&P 500 ten-year returns have been very muted. In many instances, subsequent ten-year annualised returns have generally been negative or flat. So, historical data suggest that US returns over the ensuing ten years are likely to be uninspiring at an index level. However, this does not necessarily imply that all US stocks will deliver such muted returns over the period. Instead, it suggests that index-level (such as the S&P 500) returns for US equities are likely to be modest over the next decade, even if select companies continue to generate robust returns.

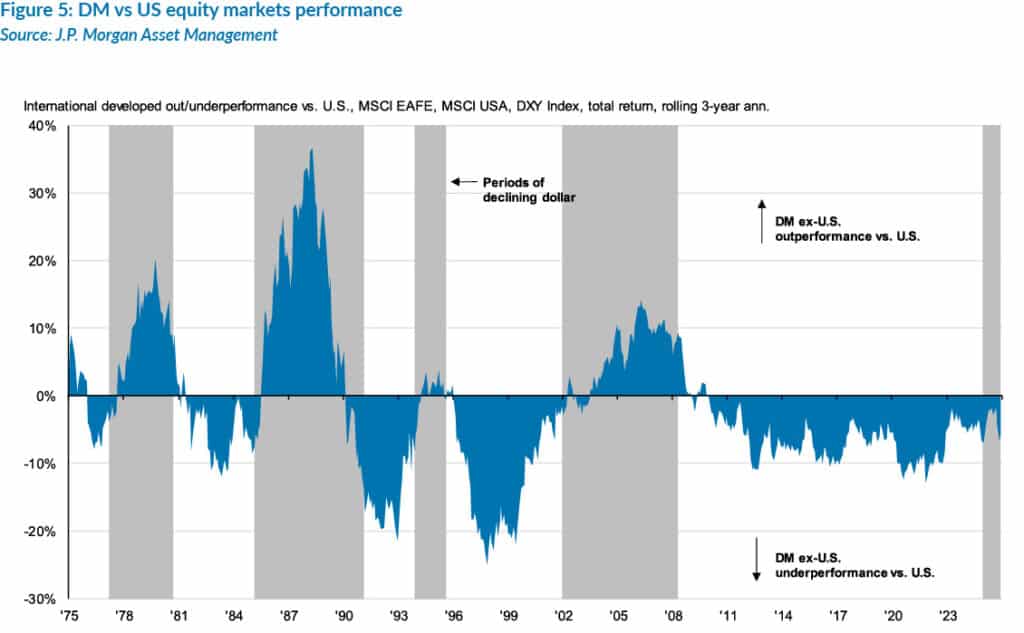

We next turn to earnings growth rates, which have been a critical driver of US equity markets’ outperformance over the past fifteen years. As illustrated in Figure 5, US returns have outperformed those of developed markets (DMs) ex-US meaningfully since c. 2010. Higher US earnings growth has been a major driver of that outperformance, with US earnings up nearly fivefold since 2010. US technology leadership over the past fifteen years across mobile, cloud, enterprise software and artificial intelligence (AI) has led to an explosion in earnings growth (Figure 6). By contrast, earnings growth in the rest of the world over the same timeframe was far more muted, failing even to double.

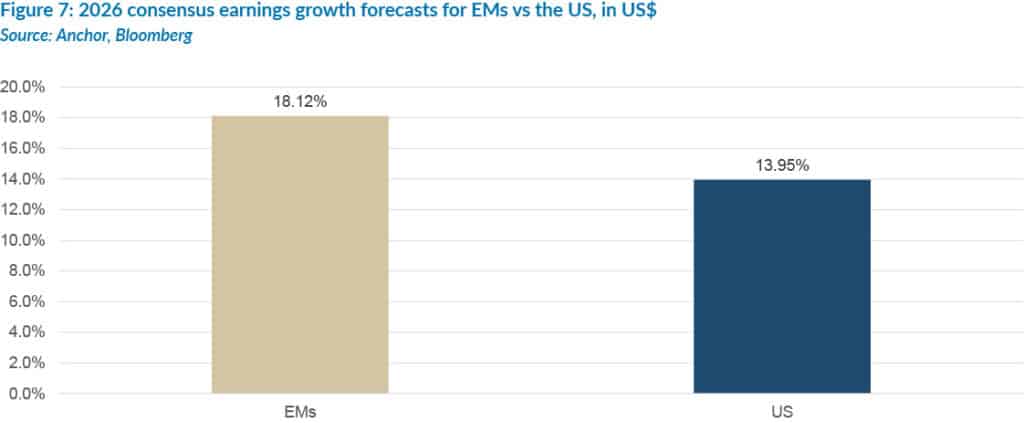

Interestingly, we may now be seeing that gap in relative earnings growth narrowing. Earnings expectations in emerging markets (EMs) have begun to improve, with consensus forecasts pointing to 18.1% earnings growth for EMs vs 14.0% for the US in 2026 (Figure 7). Whether this represents a cyclical rebound or a more structural shift remains to be seen. For now, it is one sign of a potentially improving investment opportunity set in EMs.

*Dots represent monthly data points since 1988 (earliest available). The forward P/E ratio is the price to 12-month forward earnings, calculated using IBES earnings estimates. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current and future results.

The US has earned its outperformance vs the rest of the world since 2010, as the world came out of the global financial crisis (GFC). Strong earnings growth, driven by technology leadership, was the main driver of that outperformance. The starting point of a 14x forward P/E in 2010 also created a powerful environment for earnings expansion and a multiple re-rating over the subsequent fifteen years. Today’s backdrop is different. Elevated valuations, muted long-term return prospects at an index level, and a potentially improving earnings outlook in other regions justify investors not going all in on the US.

This is not a call to avoid the US market. It remains home to many world-class businesses, and attractive stock-specific opportunities are likely to emerge both now and over the next few years. Instead, we argue that investors should not focus solely on the US. At this point in the cycle, a more diversified global allocation appears prudent as US index-level returns are likely to be modest over the next ten years. Exclusive reliance on US equities increases concentration risk, especially when long-term return expectations appear constrained. Anything is possible in the short term, as Figure 3 demonstrates, but the balance of evidence suggests that investors should avoid placing all their eggs in the US basket. Developed markets ex-US and EMs also deserve consideration.