Over the past two years, central banks have raised interest rates significantly in an attempt to manage post-pandemic inflation. The central thesis was that these rate hikes would slow down economic activity by increasing borrowing costs, thus dampening consumer spending and investments. Despite these expectations, the global economy has demonstrated remarkable resilience, with significant slowdowns observed only in certain regions.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the varied responses to higher interest rates stem partly from the distinct differences in housing and mortgage market structures across countries. The housing market is a crucial conduit through which monetary policy influences economic activity, with mortgages (or home loans), one of the largest household liabilities, playing a significant role. Therefore, understanding the characteristics of housing and mortgage markets is key to explaining why rising interest rates affect some economies more than others.

The role of housing and mortgage characteristics in monetary policy transmission

In most economies, real estate serves as both a primary form of household wealth and a significant source of employment and investment. Given the centrality of housing to many national economies, the characteristics of mortgage markets play a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness of monetary policy. Mortgages are particularly sensitive to interest rate changes, as higher rates typically translate to increased mortgage payments, thereby affecting household budgets and consumption patterns. However, these effects differ significantly across countries based on two main factors: the prevalence of fixed-rate vs variable-rate mortgages and the ratio of household debt to GDP.

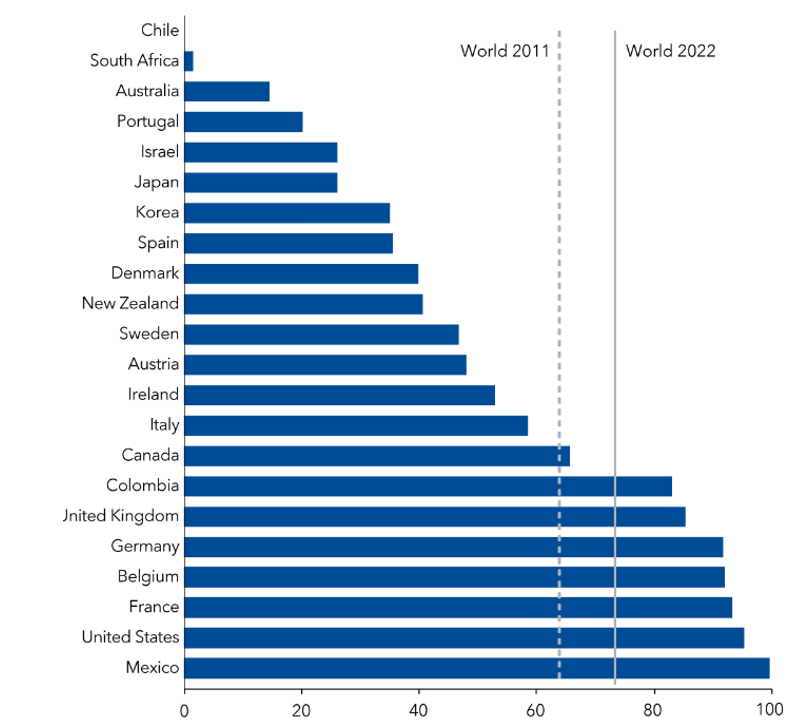

For instance, in countries like South Africa (SA), where a high proportion of households have variable-rate mortgages and fixed-rate mortgages are nearly non-existent, the impact of rate hikes is felt more immediately. As interest rates rise, mortgage payments adjust accordingly, putting immediate financial strain on these households. In contrast, in the US and Mexico, where over 95% of mortgages are fixed-rate, households with mortgages are largely shielded from immediate rate hikes, meaning their monthly payments remain stable despite central bank actions. This buffering effect reduces the sensitivity of these economies to monetary tightening, as fewer households experience increased financial strain in the short term.

Figure 1: Country-level share of fixed-rate mortgages

Source: IMF

*% of country-level stock mortgaged, 4Q22

The Impact of debt levels and housing supply constraints

Higher interest rates also exert a stronger effect in countries where mortgages represent a larger share of household debt and where household debt is high relative to GDP. In these situations, larger segments of the population are affected by rising rates, particularly when mortgage debt is substantial compared to the value of the homes. This heightened exposure makes these economies more susceptible to monetary tightening effects as more households adjust their consumption in response to increased mortgage payments.

Moreover, housing supply constraints amplify the influence of interest rates. When the housing supply is restricted, lower interest rates can spur demand without a corresponding increase in housing availability, driving up home prices and making property ownership a means of wealth accumulation. For homeowners, increased property values enhance their net worth, which may lead to increased spending, especially if they can use their homes as collateral. Conversely, where home prices have recently been overvalued, a sudden rate increase can trigger sharp declines in home values, leading to falling household wealth, foreclosures, and, ultimately, declines in consumption and economic activity.

Evolving housing and mortgage markets since the GFC and COVID-19

Mortgage and housing markets have evolved considerably in recent years, influenced by the global financial crisis (GFC) and the COVID-19 pandemic. At the outset of the latest rate-hiking cycle, mortgage interest payments were at historically low levels, and mortgage terms were often longer and more likely to be fixed-rate. Additionally, the pandemic spurred migration from urban areas to regions with fewer housing supply restrictions, altering housing demand patterns.

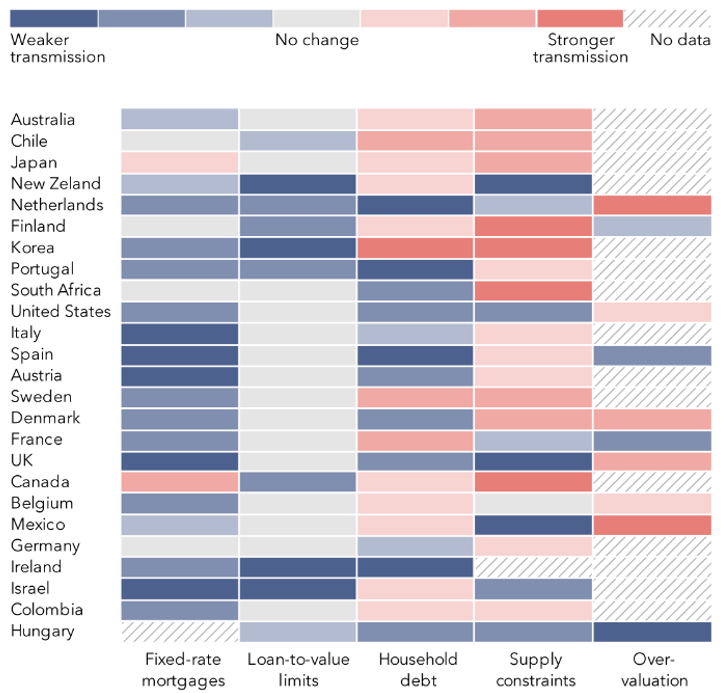

As a result, the housing market’s role in transmitting monetary policy appears to have weakened or been delayed in certain countries, allowing some economies to maintain steady growth despite higher rates. In nations like Canada and Japan, however, changes such as a declining share of fixed-rate mortgages, rising debt levels, and constrained housing supplies have strengthened the transmission of monetary policy through the housing sector. In contrast, in countries such as Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, and the US, factors such as longer fixed-rate mortgage terms and lower debt levels have weakened the impact of monetary policy on the housing market.

In Figure 2 below, we highlight the IMF’s findings regarding shifts in housing and mortgage characteristics, which have led to a weakening of monetary policy transmission in some countries (blue) and a strengthening in others (red).

Figure 2: Housing channels- IMF findings

Source: IMF

Monetary policy implications and the risk of overtightening

The varied impact of monetary policy across countries underscores the importance of a nuanced, country-specific approach to economic policy. In countries with strong housing channels, close monitoring of housing market trends and household debt can provide early warning signs of financial strain, allowing central banks to adjust their policies before significant damage occurs. On the other hand, in economies with weaker housing transmission, central banks may find it beneficial to act more decisively at the first signs of overheating to curb inflation.

Today, most central banks have made progress toward their inflation targets. However, the lagged effects of fixed-rate mortgages, particularly those with short fixation periods, could make monetary policy transmission suddenly more effective as these rates reset. For heavily indebted households, this transition could lead to rapid declines in consumption and economic hardship. Therefore, while tightening monetary policy has been widely used to manage inflation, keeping rates high for an extended period could risk overtightening, harming household welfare and economic stability.

Overall, differences in mortgage structures, debt levels, and housing supply constraints lead to diverse impacts of higher interest rates on national economies. Countries with a high proportion of variable-rate mortgages, high household debt, and constrained housing supply are more immediately affected by rate hikes. In contrast, nations with high fixed-rate mortgage shares, more balanced debt levels, and less restrictive housing markets experience milder impacts, often with delayed economic effects. For policymakers, this underscores the importance of tailoring monetary policy to national economic conditions. In a globally connected economy, these nuanced approaches can ensure that efforts to combat inflation do not lead to unintended economic consequences, such as increased unemployment or reduced consumer spending.