When unpacking such a big topic it’s helpful to start from first principles. In this case, the most fundamental question is: “Why do companies exist?” Otherwise stated, “What is their purpose?” The standard answer for several decades, at least in Anglo-Saxon countries, has been “to maximise shareholder value”. More recently, ‘stakeholders’ have taken precedence over ‘shareholders’.

Understanding companies’ reason for being leads to the next question: “What makes a good company?” Finally, stepping from the conceptual to the practical, we then ask, “What makes a good stock?” Noting of course the truism that good companies don’t always make good stocks!

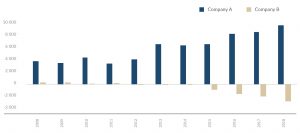

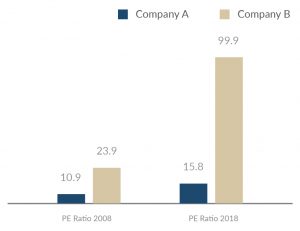

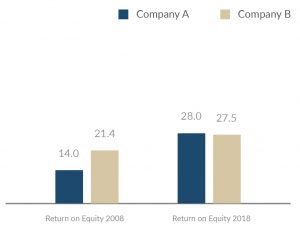

We compare the metrics of two real companies using data from 2008 to 2018. As you consider the charts below, ask yourself: 1) which was the better company; and 2) which was the better stock?

Figure 1: Free cash flow ($mn)

Source: Anchor

Figure 2: PE Ratios

Source: Anchor

Figure 3: Return on equity

Source: Anchor

It turns out that Company A created substantial value – its market capitalisation increased an impressive $121.2bn over the decade, with the share compounding at 14.5% p.a. (excluding dividends). Company B delivered slightly less value in aggregate, growing its market capitalisation by $115bn. And yet Company B’s stock was a massive outperformer, compounding at over 52% p.a.

Company A and Company B are The Walt Disney Co. (Disney) and Netflix, respectively. What is particularly remarkable, is that Netflix’s market capitalisation increased from $1.8bn to $117bn over the period. The acorn became an oak tree.

How did this happen?

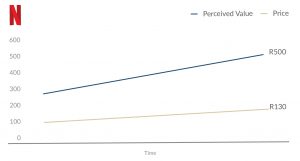

We believe that Netflix’s founder and CEO, Reed Hastings, understands a fundamental truth: companies exist to deliver value to customers and the best companies deliver more value than they capture. Netflix’s share price has grown rapidly as a bi-product of the external value the company has created.

South African subscribers to Netflix currently pay around R130 per month. We suspect that many subscribers perceive the value to be as high as R500 per month. The gap between the perceived value of the service and the price is one way of thinking about the aggregate value Netflix is ‘giving away’ to consumers.

Figure 4: Netflix offers compelling value to consumers

Source: Anchor

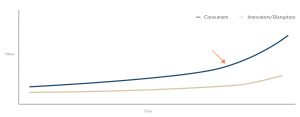

Netflix is used to illustrate a broader point. Other major innovators and disruptors (Amazon, Alibaba, Google etc.) have operated on the same principle over the past decade. The red arrow in Figure 5 denotes the impact of the internet, which facilitated the delivery of value to consumers on an unprecedented scale.

Figure 5: Internet disruptors have generated substantial value for consumers and shareholders

Source: Anchor

By contrast, many legacy brand owners have rested on their laurels for too long and no longer offer consumers a compelling value proposition. This dynamic has been most prevalent in the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods space, where Kraft Heinz recently fell an astonishing 27% in a single day after writing off over $15bn in goodwill relating to its Kraft and Oscar Mayer brands. Kraft Heinz has shed roughly $60bn in market capitalisation in the past 18 months – a stunning fall from grace for what was previously considered a high-quality, defensive business.

The Kraft Heinz episode reveals the flaws in the “shareholder value maximisation” ideology. While the ‘3G Model’ of slashing costs to boost margins and shareholder returns enjoyed initial success, it has ultimately resulted in long-term value destruction.

The term ‘moat’ has been used to describe a firm’s source of competitive advantage. Many legacy brands no longer qualify as moats, possessing neither the ability to drive purchasing decisions nor pricing power. This does not discredit the moat as a conceptual model. The core principles remain unchanged, but the manifestations and applications thereof constantly evolve.

The Disney-Netflix comparison provides an important insight into the relationship between moats and share price performance. The absolute size of the moat is less important than the direction in which it is moving. It is hard to argue against Disney being a better company over the past decade, given its prodigious cash flows and attractive returns on capital. However, while Disney has been a partial casualty of the fraying cable bundle, Netflix has rapidly built an impressive moat in video streaming.

The direction of Disney and Netflix’s moats over the next decade is a source of intense debate and analysis within Anchor (Disclosure: we hold both shares on behalf of clients in different mandates). Based on the framework we’ve established above, it stands to reason that the company that delivers the greatest aggregate consumer value will build the deepest moat and generate the highest market returns.

In the short term, none of this matters. The share prices of Disney and Netflix are hostage to the latest newsflow on trade wars, Trump, Brexit, interest rates … the list is endless. It is only in the fullness of time – often a decade or more – in which their steady efforts translate into outsized returns. Only by gaining a deep fundamental understanding of the “Why” and the “How” – why companies exist and how they deliver value – are we able to endure the vicissitudes of the market and participate in their long-term returns. This is what really matters in equity investing.