Sovereign debt defaults have become a hot economic topic lately due to a confluence of global and regional factors. High debt levels accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic are straining many economies, especially as rising interest rates (driven by central banks combatting inflation) have made debt servicing more expensive, particularly for nations with foreign-denominated obligations. Inflation, fuelled by supply chain disruptions, volatile commodity prices, and geopolitical tensions like Russia’s war on Ukraine, has further compounded economic pressures. In many countries, sharp currency depreciations have made it even costlier to repay external debt, heightening the risk of default. Additionally, the impact of climate change and natural disasters has hit vulnerable economies hard. At the same time, China’s growing role as a lender through ambitious plans like the US$1trn Belt and Road Initiative ([BRI], also referred to as the One Belt One Road or the New Silk Road, essentially a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013 to improve connectivity between China, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa) has added complexity to debt sustainability. Countries like Sri Lanka, Argentina, and Zambia have already sought International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts or debt restructuring, amplifying concerns about global financial stability and the potential ripple effects of widespread defaults.

In July, Ukraine narrowly avoided defaulting on US$20bn in loans by reaching a tentative agreement with private creditors. Over the past two years, the country has paused interest payments on its international debt due to the heavy financial strain of the war, with the suspension set to end on 1 August 2024. Without this new restructuring deal, Ukraine’s default would have ranked among the ten largest in modern history. The country last defaulted in 2015 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

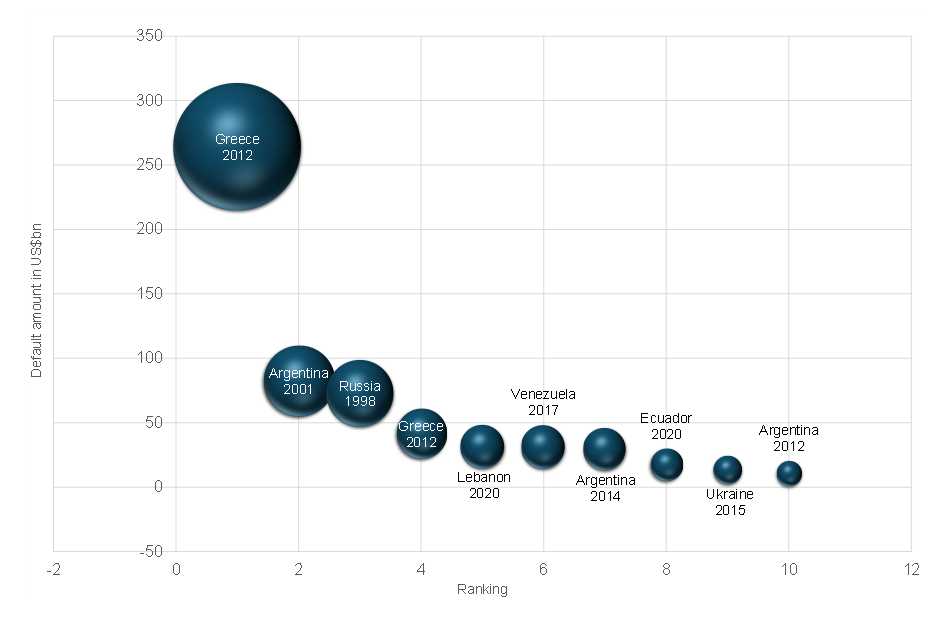

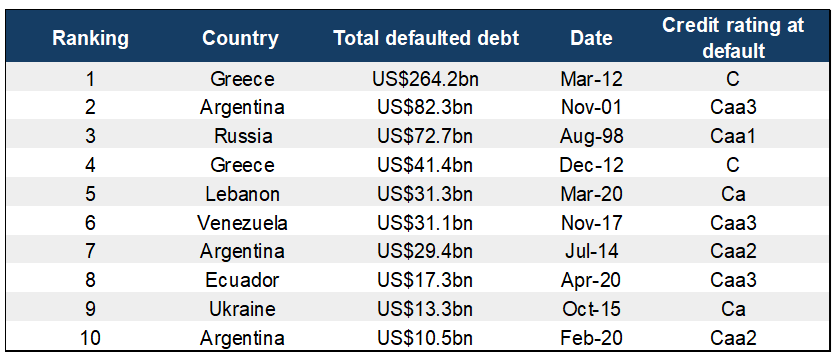

The largest recorded default occurred in 2012 when Greece failed to repay US$264.2bn amid a prolonged recession. Greece defaulted again just nine months later, marking the fourth-largest default ever. Before the crisis, Greece had run large deficits despite being one of Europe’s fastest-growing economies. In 2009, the newly elected prime minister revealed that the country was US$410bn in debt—far more than previously estimated. The second-largest default occurred in Argentina in 2001, when the government failed to pay interest on US$82.3bn in foreign debt. Argentina has defaulted several times since gaining independence in 1816 and is currently the largest debtor to the IMF despite being Latin America’s third-largest economy. Russia’s 1998 default on US$72.7bn ranks next, coinciding with a currency crisis that wiped out over two-thirds of the rouble’s value in just weeks. That year, other countries like Venezuela, Pakistan, and Ukraine also defaulted, driven by instability following the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Similar waves of defaults occurred in 2020 when the global pandemic and plummeting oil prices led to seven sovereign defaults. Among the most significant were Lebanon, Ecuador, and Argentina, grappling with deepening fiscal crises.

Figure 1: Top-10 sovereign debt default between 1983 and 2022

Source: Anchor, Moody’s

Figure 2: Top-10 sovereign defaults and the country’s respective credit rating at the time of default between 1983 and 2022

Source: Anchor, Moody’s

Sovereign debt defaults occur when a country fails to meet its debt obligations, either by missing payments on interest or being unable to repay the principal amount borrowed. While these defaults primarily affect the defaulting nation, the consequences often extend far beyond national borders, impacting the global economy due to the interconnectedness of international markets. As such, understanding the causes of sovereign defaults, the domestic fallout, and the broader global impact is essential for policymakers, investors, and international organisations alike. The causes of sovereign debt defaults vary but often stem from a combination of excessive borrowing, economic mismanagement, currency depreciation, external economic shocks, and political instability. Excessive borrowing is a key factor, as many governments accumulate large debt to finance public spending or infrastructure projects. However, when debt levels outpace a country’s economic growth, the debt becomes unsustainable. This issue is often compounded by poor economic policies, such as inefficient spending and a failure to generate sufficient revenues. Financial mismanagement, including corruption or wasteful government spending, exacerbates the country’s debt burden and reduces its ability to meet its obligations.

Another common cause of defaults is currency depreciation, particularly for countries that borrow in foreign currencies. A significant drop in the value of the local currency increases the real value of foreign-denominated debt, making repayment much more challenging. External economic shocks, such as sudden declines in the prices of key exports like oil or agricultural products, also strain a country’s ability to service its debt. For countries heavily reliant on commodity exports, a collapse in global prices can drastically reduce national revenues, pushing them closer to default. Political instability can further undermine a country’s financial health. When governments face internal unrest or regime changes, economic policies may become unpredictable or poorly managed, leading to a loss of investor confidence and, ultimately, default.

The consequences for the defaulting country are often severe, with a confluence of economic, social and political ramifications. One of the immediate impacts is the loss of access to international credit markets. Following a default, investors are typically reluctant to lend to the defaulting nation or demand much higher interest rates to compensate for the perceived risk. This loss of market access makes it difficult for the country to borrow funds for essential development projects, infrastructure, or economic recovery efforts. The inability to secure loans exacerbates the country’s financial troubles and deepens its economic contraction. Economic recession is another significant consequence of sovereign defaults. When a government defaults, its ability to stimulate the economy through spending is sharply curtailed, leading to lower economic activity, rising unemployment, and reduced consumer confidence. This contraction often creates a vicious cycle, with falling revenues making it even harder to repay debts.

The devaluation of the national currency that often accompanies a default frequently leads to skyrocketing inflation. The prices of imported goods rise rapidly, eroding purchasing power and further lowering living standards for the population. High inflation, coupled with unemployment, disproportionately impacts lower-income households, worsening poverty and inequality. To stabilise the economy and regain the confidence of international lenders, defaulting countries frequently implement austerity measures. These policies, which involve cutting public spending, raising taxes, and reducing deficits, are often conditions imposed by international financial institutions like the IMF. While austerity can help restore fiscal discipline, it usually worsens short-term economic conditions, reducing demand and investment. The social consequences of austerity are profound, frequently leading to widespread discontent, protests, and political instability. In countries like Greece and Argentina, austerity measures sparked mass demonstrations and significant political upheaval.

While the national consequences of sovereign debt defaults are severe, the global economic impact is equally significant. Sovereign defaults create instability in international financial markets. Investors who hold the defaulting country’s bonds suffer losses, and this can lead to a broader reassessment of risk in global markets. Fear of contagion often spreads to other countries with similar economic vulnerabilities, causing investors to pull out of those markets as well. For example, during the eurozone debt crisis, Greece’s default raised concerns about the fiscal health of other European countries, like Portugal, Spain, and Italy. This fear drove up borrowing costs across the region and threatened to destabilise the entire eurozone. Sovereign defaults can also disrupt global trade flows. When a country defaults, its currency typically depreciates, making imports far more expensive and reducing purchasing power. This leads to a sharp drop in demand for imported goods, affecting the countries that export to the defaulting nation. At the same time, the defaulting country may struggle to afford essential imports, causing supply chain disruptions that ripple through the global economy. As an example, if a major oil-exporting country defaults, global commodity prices can be affected, disrupting both markets and trade.

The global banking sector is particularly vulnerable to sovereign defaults, as international banks often hold large amounts of government bonds. A default can lead to significant losses for these banks, reducing liquidity and constraining their lending ability. The 1998 Russian default, for example, led to massive losses for global banks and hedge funds, nearly triggering a global financial crisis. In such cases, the effects of sovereign defaults can spread far beyond the borders of the defaulting nation, threatening the stability of the international financial system.

International institutions, particularly the IMF and the World Bank, often intervene in sovereign defaults to stabilise the situation and prevent the crisis from spreading. These institutions provide financial assistance to the defaulting country, but such aid typically comes with stringent conditions, including implementing economic reforms. While these interventions are designed to restore stability, they can sometimes prolong the economic hardship in the defaulting country by imposing austerity measures that exacerbate recessionary conditions. Sovereign defaults also have broader implications for global confidence and can trigger contagion risks. When one country defaults, investors may become wary of lending to other nations with similar economic challenges. This heightened sense of risk leads to higher borrowing costs, especially for emerging markets (EMs) that rely heavily on international capital. In extreme cases, a major default can erode confidence in entire regions or global markets, as seen during the eurozone crisis.

Ultimately, sovereign debt defaults arise from a complex combination of excessive borrowing, poor economic management, external shocks, and political instability. While the consequences are most severe for the defaulting country -leading to recession, inflation, loss of market access, and social unrest – the global economic impact can be equally profound. Financial markets, international trade, and global banking systems all feel the effects of a sovereign default, often requiring multilateral intervention to manage the fallout. As global economies become increasingly interdependent, the repercussions of sovereign defaults will continue to pose significant risks to national and international economic stability. However, in situations where debt is truly unsustainable, it is worth bearing in mind that a default may provide an opportunity for longer-term recovery and stabilisation, especially if handled carefully through negotiations with creditors and international organisations.