Africa is not a monolith, but a continent of striking contrasts and interconnected possibilities. It encompasses everything from mineral-rich highlands and expansive agricultural zones to fast-growing tech ecosystems and globally sought-after tourism hotspots. Its geography stretches across 30mn square kilometres, housing vibrant megacities, sophisticated financial centres, strategic port networks, and millions of rural communities that support both local economies and global supply chains. This complexity defies the reductive narratives that often dominate external viewpoints. Africa’s economic and social realities are as layered as its cultural and ecological diversity. Yet, despite its scale and strategic relevance, the continent remains widely misunderstood and underappreciated, particularly in investment circles. This is due, in part, to outdated perceptions, structural data limitations, and an overreliance on broad generalisations.

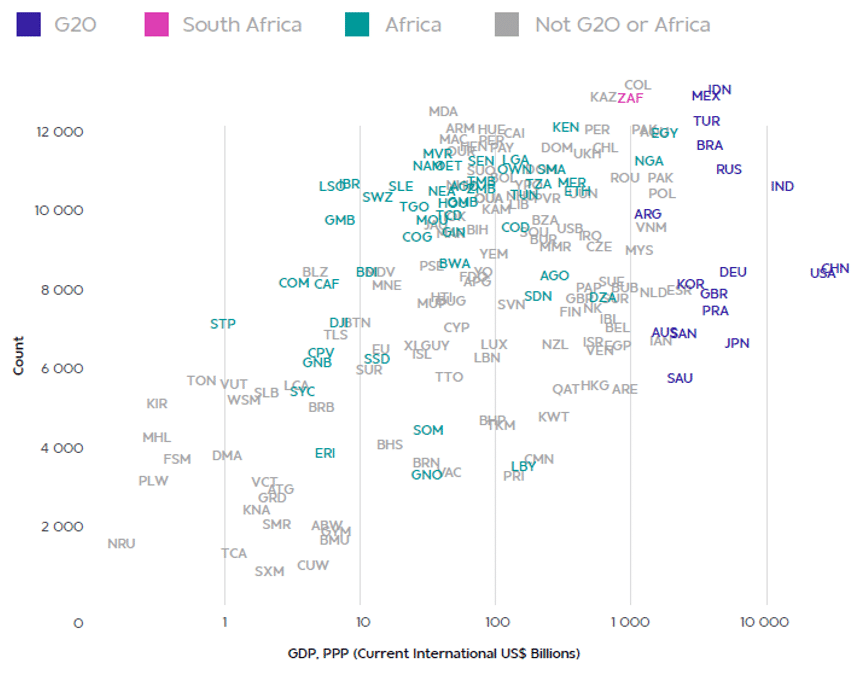

Incomplete and inconsistent data coverage remains a major challenge, affecting everything from public health responses to investment decisions. This data gap extends to economic assessments. Investors, policymakers, business leaders, and scholars frequently encounter opaque or incomplete information when evaluating African markets. A large portion of Africa’s economy remains informal, meaning that economic activity is often unrecorded or difficult to track using traditional methods. For example, in 2018, McKinsey & Co. could identify only 338 African companies with annual revenues above US$1bn, while the estimated number of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) exceeded 80mn.

Moreover, unreliable reporting and corruption, exacerbated by conflict zones in parts of the continent, further complicate data collection and economic evaluation. Even large international databases reflect these gaps. The United Nations National Accounts database, for example, had received fewer than half of the expected GDP data points from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries for the 1991–2004 period, with full annual data missing entirely for 15 countries.

Figure 1: Number of indicators available from the World Bank

Source: Codera Analytics, RMB

Nonetheless, this picture is beginning to change. As Africa becomes more digitally integrated and data infrastructure improves, analysts now have access to more reliable and timely information than ever before. These advancements are critical for shaping informed policy, guiding strategic investments, and correcting outdated narratives about Africa’s economic potential.

As we shift towards the midpoint of 2025, macroeconomic signals from across the continent reflect cautious optimism. Many African countries are beginning to ease monetary policy after a prolonged period of high inflation and elevated interest rates. Declining inflation, stabilised currencies, subdued domestic demand, and favourable base effects largely support this policy shift. That being said, disinflation remains uneven. Some countries continue to grapple with elevated food and energy prices, subsidy rollbacks, and currency depreciation. Despite these headwinds, African policymakers are increasingly focused on striking a balance between fostering economic growth, addressing pressing social needs, and maintaining financial stability. Encouragingly, several governments are building fiscal and external buffers, and fiscal consolidation efforts are already contributing to more sustainable debt ratios. These macroeconomic adjustments are creating a more stable and predictable environment for investment and long-term planning.

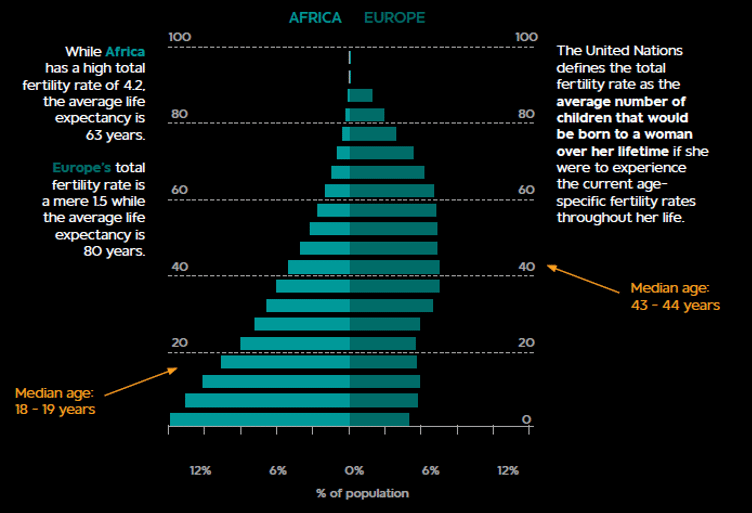

One of the most compelling reasons to pay closer attention to Africa is its demographic trajectory. In 1900, Africa’s population was approximately 140mn—just 9% of the world’s total. Today, it stands at over 1.4bn or 18% of the global population, and by 2050, it is projected to reach 2.5bn, roughly one-quarter of humanity. Unlike many high-income nations facing demographic decline, Africa has a rapidly growing and youthful population. A rising share of this population will be of working age over the coming decades, offering the potential for a significant demographic dividend. If properly harnessed, this expanding workforce could fuel sustained economic growth and innovation. Yet, this dividend is not guaranteed. It depends on strategic investment in education, health, infrastructure, and job creation. Without these, the potential demographic advantage could morph into a source of instability. The stakes are high, but so too is the opportunity.

Figure 2: Population pyramid for Africa vs Europe

Source: RMB

Africa’s natural resource wealth also positions it as a critical player in the global economy. The continent is home to around 30% of the world’s critical mineral reserves and nearly two-thirds of its remaining uncultivated arable land. Yet paradoxically, Africa remains a net food importer. Offshore, three of the world’s four most productive marine ecosystems—the Canary, Benguela, and Somali Currents—hug Africa’s coastline, offering vast potential for blue economy development.

The global shift toward electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy technologies adds further strategic importance to Africa’s mineral endowment. For example, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Tanzania collectively hold over 20% of global graphite reserves—vital for EV battery production. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) alone produces about 70% of the world’s cobalt, another essential mineral for clean energy systems. However, these resources can either catalyse development or perpetuate the so-called “resource curse.” Norway’s use of oil revenues to build a sovereign wealth fund valued at over US$290,000 per citizen illustrates how governance and policy, not just resource abundance, determine economic outcomes. Angola, with comparable oil reserves, has followed a markedly different path. Africa’s potential lies not just in what it has, but in how it stewards those assets.

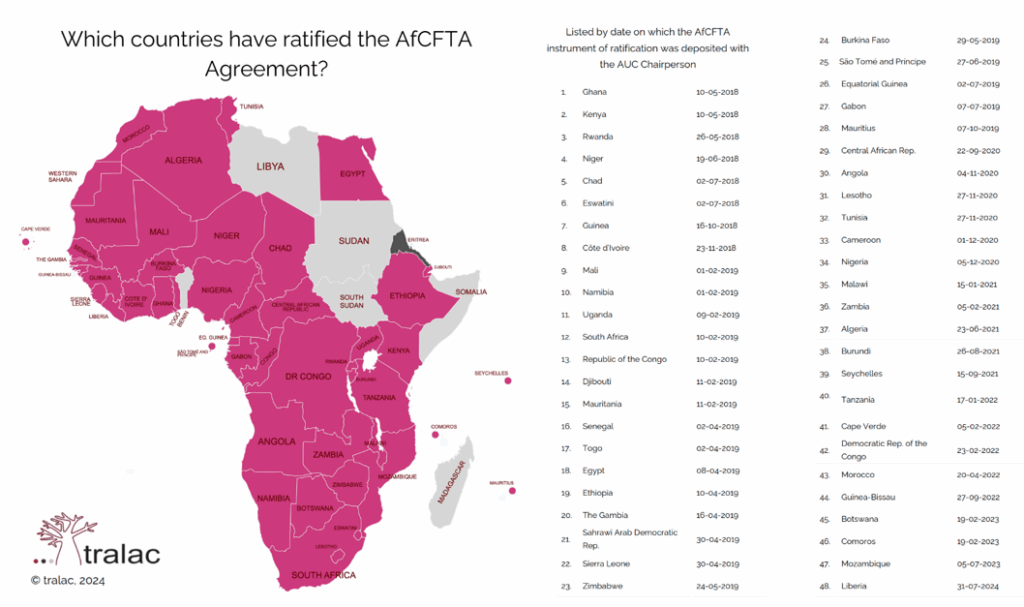

Another area with transformative promise is intra-African trade. Currently, only about 15% of Africa’s trade is within the continent, far below Europe’s 67%. Trade volumes among African countries have barely grown over the past decade, rising from US$98bn in 2013 to just US$102bn in 2022. Furthermore, trade is concentrated in a handful of countries—South Africa (SA) alone accounts for nearly one-third of all intra-African trade, followed distantly by the DRC, Nigeria, and Egypt.

Unlocking intra-African trade could be a game-changer. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a flagship initiative under the African Union’s Agenda 2063, aims to do just that. The AfCFTA seeks to create a unified market for goods and services across the continent, reduce tariffs and non-tariff barriers, and promote investment, innovation, and mobility. If fully implemented, the World Bank estimates the agreement could boost regional income by 7%, lift 30mn people out of extreme poverty, and significantly accelerate wage growth by 2035.

With 48 of 54 signatories having ratified the agreement as of August 2024, AfCFTA is poised to become the world’s largest free trade zone by number of participating countries. Its success will depend on resolving key implementation hurdles such as tariff concessions, rules of origin, and the dismantling of non-tariff barriers. Customs reforms, improved border logistics, and harmonised regulatory frameworks are essential.

Figure 3: Countries that have ratified the AfCFTA agreement as at August 2024

Source: Tralac

In a world increasingly characterised by geopolitical fragmentation, supply chain realignment, and demographic ageing in major economies, Africa offers a rare and powerful combination of growth potential, resource depth, youthful human capital, and regional ambition. For forward-looking investors, business leaders, and development partners, the question is no longer whether Africa matters but how best to engage with its evolving, increasingly central role in the global economy.

As global dynamics shift (geopolitically, economically, and demographically), it is more critical than ever to engage with Africa on its own terms, recognising its vast heterogeneity and untapped economic promise. Doing so is not just a moral or intellectual imperative- it is a pragmatic one for those looking to understand where the next wave of global growth and innovation is likely to emerge.