The conclusion of the week-long 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CCP) on Sunday (23 October) saw the much-anticipated unveiling of the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) members – essentially the seven most powerful men in China.

The congress involved 2,000 CCP delegates, and its intention is predominantly to elect leadership, with last year’s National Party Conference (NCP) already setting out the policies for the party over the next five years (Five-Year Plan [2021-2025]) – see our report entitled Making sense of China’s regulatory crackdown, dated 10 August 2021.

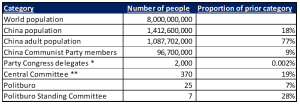

To put the congress delegates (and China’s population in general) in context, Figure 1 below summarises the filtration process that gets us to the number of Politburo and Standing Committee members.

Figure 1: The filtration process for the Politburo and Standing Committee members

Source: Anchor

*Provincial leaders, top military officials, farmers, and minority representatives. **200 full members and 170 alternates.

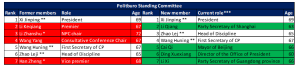

In the table in Figure 2, we summarise the changes at the top of the Politburo.

Figure 2: The 20th National Congress of the CCP changes to top party leadership

Source: Anchor

*Members not eligible for re-election because of age (> 67). **Members re-elected. ***The official roles of new members will only be announced in March 2023.

The changes in the membership of the PSC can be grouped as follows:

- Members who have kept their positions:

- Wang Huning – an academic and ideolog. He is believed to be the writer of most of the CCP’s ideological concepts, including the “Xi Jinping Thought” – described as “socialism with Chinese characteristics” that party members are required to study and use as guiding principles for their actions.

- Zhao Leji – head of party discipline and leader of the anti-corruption crackdown, which was a key tenant of Xi’s early leadership (and, perhaps for the cynical, helped Xi remove corrupt factions that opposed him or threatened control).

- Members retiring for age reasons (> 67 years):

- Li Zhanshu (72).

- Hang Zheng (68).

- Moderate members pushed out by Xi:

- Li Keqiang (67) – the current premier, who will see his term as a premier end in March 2023 (when Xi removed the age and term limits for his presidency, he did not do the same for the premier’s office). Li was happy to challenge some of Xi’s policies (including his zero-COVID policy) but preferred a more consensus-style leadership. He was former President Hu Jintao’s favoured candidate to take over from him when Xi became president.

- Wang Yang (67) – represented a more liberal and less authoritarian leadership style.

- Loyalists brought in by Xi:

- Li Qiang (63) – He is the current party secretary of Shanghai and has now been elevated to the party’s second most powerful man. He is arguably relatively inexperienced for the position. However, he seems to have been rewarded for his loyalty to Xi’s zero-COVID policy when he oversaw the harsh COVID-19 lockdowns in Shanghai earlier this year. The lockdowns decimated economic activity and left Shanghai residents locked in their homes for weeks, in many cases without enough food.

- Cai Qi (66) – The Beijing mayor previously worked for Xi in the Fujian and Zhejiang provinces. He earned favour for the successful hosting of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games during the pandemic.

- Ding Xuexiang (60) – He became Xi’s secretary in 2007 and has essentially acted as Xi’s chief of staff since 2014. He is one of Xi’s most trusted aides but is, arguably, fairly inexperienced for the position.

- Li Xi (66) – He is also a Xi loyalist with close ties to Xi’s family. He has enthusiastically supported Xi’s call for more strict enforcement of party discipline.

The abovementioned changes have left Xi surrounded by loyalists, supportive of his ideologies and generally willing to take a “the end justifies the means” approach to implementing policies.

We will likely have to wait until China’s Central Economic Work Conference in December to better understand what these appointments mean for economic policy over the short- to medium-term. Official parliamentary positions will likely only be known in March 2023, when China’s Parliament convenes.

Below we highlight the other notable outcomes of the 20th National Congress of the CCP. These include:

1) Revisions to the party charter (basically the CCP’s constitution) included the following:

- Defining Xi as the “Core of the Party” and cementing his ideas as the party’s guiding principles.

- Recognising the party as the “supreme political leadership force”.

- Promoting “Chinese-style modernisation”.

- Gradually achieving “common prosperity”.

- Developing “fighting spirit”, strengthening fighting ability.

- Upping the ante on Taiwan to “firmly oppose and contain Taiwanese independence” and “advance the “one country, two systems” model.

- Requiring political loyalty in the military.

All of the charter’s revisions seem aimed at entrenching Xi’s absolute power over the party, ingraining the party’s absolute power in defining the principles for living life in China and taking a more authoritarian approach to enforcing those things.

- The removal of Former Chinese President Hu Jintao from the closing session of the congress.

- Former President Hu Jintao was Xi’s predecessor, ruling from 2002–2012 and is currently 79.

- Hu oversaw a prosperous period for the Chinese economy, characterised by increasing liberalisation and opening up the Chinese economy. However, it was also a period during which corruption appeared to thrive.

- Hu was removed from the closing session of the congress in a very public display as it occurred shortly after the media were allowed into the final part of the session. He appeared confused about what was happening and somewhat reluctant to leave.

- While there was no official comment on the event at the time, the official line is that he felt ill and needed to be helped out.

- Sceptics point to the timing (as the media was let in) as a well-choreographed display of power in removing the former leader who has preferred a more liberal and inclusive form of governance and who was believed to have been close to members who have looked to speak out against some of Xi’s policies (like Li Keqiang).

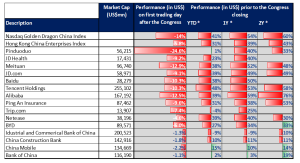

Monday’s (24 October) market reaction to the outcomes of the CCP congress has shown how uncomfortable investors are with these changes, with Monday’s collapse happening after many of the foreign-listed Chinese companies had already seen their share prices halve over the past year.

Figure 3: The performance of foreign-listed Chinese companies and indices

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

*Performance up to 22 October (the last trading day before the Congress closed).

The changes feel particularly uncomfortable when the world is already dealing with the fallout from the actions of another authoritarian leader, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and the consequences that this has had, not only on global security but also food and energy prices. As global investors, it is hard to ignore the opportunities presented by the world’s second-largest economy, but what is clear is that the ability to deploy capital in China is increasingly fraught with complexity. The challenge will be to decide whether we are nearing the trough of an extraordinarily painful regulatory cycle or whether China is now structurally less investable for public market investors. The reality is likely between those extremes and will vary by sector depending on how well the companies’ objectives align with the CCP’s strategic priorities. For investors able to successfully navigate this complexity, the rewards are likely to be meaningful.