Reflecting on the South African equity market’s performance over the last few years, one rather unsettling observation has been the unusually large number of blue-chip companies that have recorded dramatic price declines over a short space of time.

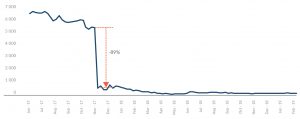

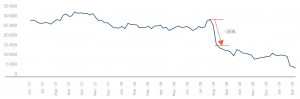

Steinhoff and Aspen, which suffered share price declines of 89% and 35%, respectively, over a few days, spring to mind. However, there were others too: Mediclinic, EOH etc.

Figure 1: Steinhoff share price (ZAc)

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 2: Aspen share price (ZAc)

Source: Bloomberg

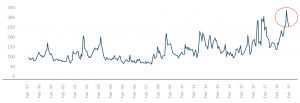

The reasons for these precipitous falls varied, but there was one constant – the damage these companies did to their investors’ wealth. Given one’s inability to predict these types of events ahead of time, as well as the tax consequences which accompany trading, are there ways to mitigate such risks? Indeed, with global economic uncertainty at the highest levels in 20 years, it would seem an opportune time to take a practical look at some protection strategies available to an investor.

Figure 3: Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index

Source: Baker, Bloom & Davis

Before identifying some of the specific derivative strategies that could be employed, we summarise certain broad principles to keep in mind. The concept of hedging should be compared to insurance. Typically, you wouldn’t insure your car only when you thought you were most likely to have an accident – the timing of accidents is unpredictable (as is the timing of market corrections). So, if you’re unwilling/ unable to accept the risk of being personally liable for the cost of car repairs if/ when accidents happen, then you need to accept the ongoing cost of car insurance, which will ultimately result in you paying more than you will claim over the long term.

Options, much like car insurance, are priced in a way that the underwriters are generally going to make money over time (and as such the purchasers/ hedgers are going to lose money over time – in option lingo, realised volatility is always lower than implied volatility through time).

Similarly, with investment hedging, you need to accept that the chances of you being able to time when you need portfolio insurance/ hedges are pretty slim and, as such, you will need to decide whether you are willing to accept that you will incur occasional market losses and, if not, then you will need to accept a lower long-term return in order to mitigate against occasional losses. This can be done either by having a more conservative asset allocation (i.e. less of your portfolio exposed to large potential losses) or by having a permanent hedging strategy in place. As an aside, when people are most worried about market losses, the cost of insuring against those losses is the highest.

Index and single-stock futures contracts

Strategy: Sell FTSE/ JSE Top-40 Index futures contracts up to the value of the local portfolio. The way these futures work is as follows:

The price of a FTSE/ JSE Top-40 Index future is R10 per index point. Thus, at a Top-40 index level of 49,000, each future would give an investor R490,000 (49,000 x R10) of market exposure.

One is required to post a margin in cash. This varies but, on index futures, it is 8%-10% as a rule of thumb.

Pros

This is a relatively cheap way in which to hedge. Brokerage on futures contracts is low (around R10 per contract).

Since the hedge requires you to sell a futures contract, you are ‘short’ the future. One earns interest (adjusted for expected dividends) over the period.

Cons

It is likely the weighting of shares in the portfolio will not match the index. Therefore, the hedge is an imperfect one. A material move in the price of a share, which has a weight in the portfolio that is very different to that stock’s weight in the index, will mean the hedge proves ineffective.

Should the market rise, this will result in a loss on the futures position. This will mean the benefit of a rising market is largely foregone.

The requirement to post margin, would require the portfolio to hold a cash position that may be higher than it would otherwise choose to hold.

As a possible alternative to index futures, it is viable to use single-stock futures to hedge individual stock positions in the portfolio. This could give a more accurate hedge. However, the margin requirement on single-stock futures is higher for a share that is in the top-60 on the JSE in terms of market capitalisation, the margin can be 10%-15%, depending on the volatility and liquidity of the share (the margin rises for smaller shares if single-stock futures are available at all).

Index or single-stock options?

Strategy: Buy a put option on the FTSE JSE Top-40 Index. In return for the payment of a premium, the buyer of a put option profits if the index falls below the strike price. The size of the premium paid is mainly a function of (1) the strike price relative to the current index level (the further below the current index level the strike price is, the cheaper the option); (2) volatility ( the more volatile the index is the higher the premium); and (3) time (the longer the option term, the higher the premium).

Pros

Outside of the premium paid, you do not forgo all upside should the market rally.

Cons

The premium represents a hard cost, which will be a drag on the portfolio performance in those instances where the market rallies or does not fall sufficiently for the option to be in the money (in the case of the purchase of an out of the money put).

As with index futures, the fact that the underlying portfolio does not match the index means that this is an imperfect hedge. As with futures, though, a more accurate hedge could be achieved by using single-stock options.

Options have a finite life and, on expiry, must be renewed with the payment of a further premium. If one assumes that markets rise over the long term, it is likely that the cost of maintaining a perpetual hedge against losses would more than erode returns.

Unlike a dynamic stop-loss, which one can adjust upwards as the market rises, the fixed strike price of an option means that, if the market rallies, what started out as an at-the-money hedge becomes increasingly out of the money. This means that subsequent market pullbacks are not hedged, unless the fall is to a level below the strike.

Currently, the premium payable on a put option that expires in 4 months’ time and has a strike at the current level of the index (an at-the-money option) is about 4%. This premium will differ at each point a new option is purchased, depending on the market conditions at the time, but this implies a cost of roughly 12% for full-year downside protection. There are ways to bring down this cost, which essentially involves the investor accepting some level of downside risk or being prepared to forego upside beyond a certain level. This is achieved either by purchasing an out-of-the-money put, or by purchasing an option structure (comprised of several different options that, when combined, provide a different payoff profile).

The technicalities of option structures are beyond the scope of this article, but to give a few examples of option structures that bring the cost of hedging down by the investor taking on more of the risk, we highlight the following:

A “collar” – the investor gets protection should the index/ stock decline in value, but also foregoes the upside beyond a certain level should the index/ stock rise over the term of the structure.

A “bear spread” – the investor is protected from a decline in the index/ stock, but only to a certain level, beyond which the investor carries the risk of further downside.

Tax considerations

There is no specific derivative tax legislation in SA that applies to the equity derivatives discussed above. Furthermore, there is no specific case law dealing with the tax treatment of derivative transactions like this either. As a result, the ordinary principles of South African tax law will apply to payments made or received.

Derivative positions are generally entered to serve one of the following purposes: (i) for speculative reasons, as part of a profit-making scheme; (ii) with the intention of earning a return – i.e. as a capital investment; or (iii) to hedge an underlying asset/ obligation, which may be a revenue or a capital asset.

In this instance, the use of an equity derivative (single-stock or index futures and options) is to hedge shares which are held as capital assets (or deemed a capital treatment because of the three-year, safe-haven rules). Although there is no case law precedent in this regard, it appears to be generally accepted that, where a derivative transaction is entered into with the purpose of hedging the value of a capital asset, any amount derived from that transaction should be of a capital nature.

To the extent possible, there should be a match between the nature, extent and duration of the derivative and the nature, extent and duration of the risk (equity) which is being hedged. If the equity derivative is not a perfect hedge but has a sufficiently close link to the underlying equities, it should follow the capital nature of the underlying. However, there can be many commercial (non-tax) reasons as to why a perfect hedge cannot be obtained, so as long as there is a link to the underlying, which can be demonstrated, the equity derivative can be treated as capital.

The disposal of equities that have been held for less than three years, and the fact that the South African Revenue Service (SARS) is able to apply discretion based on the pattern of trading activity, creates the risk that these transactions are deemed to be of a ‘trading’ nature and are taxed as such. So, would the use of derivatives for hedging purposes influence the decision made by SARS in these instances? Provided the intention for acquiring the equities (despite not being held for three years or longer) is to earn returns on the equity, an equity derivative concluded to hedge its risk should not taint the capital nature of the equities.

In conclusion then…

For investors who have a truly long-term investment horizon and can resist panicking in market downturns, trusting that the broadly rising tide of equity markets over time will consign these declines to barely discernable blips on the chart, the costs of hedging appear prohibitive to maintain on a perpetual basis. However, there may be many specific situations where considering some protection makes sense – a near-term need for cash or a particularly large position in an individual stock about to report results, for example. In these cases, there are solutions out there which may be worth considering. Furthermore, with considered risk sharing, the cost of these hedging solutions can be significantly reduced.