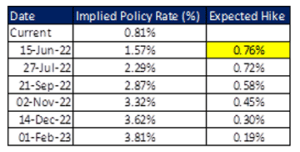

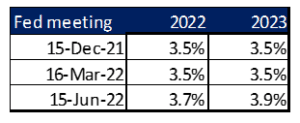

The US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met on 14-15 June to decide on the way forward for US monetary policy. The meeting followed the release of worse-than-expected US inflation data for May. Before the latest US inflation data (released on 10 June), interest rate markets were anticipating that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) would use its remaining 5 meetings in 2022 to raise rates by c. 2% – after the release of the inflation data, expectations shifted, adding another c. 0.85% of hikes over the next 5 meetings (i.e., a total of 2.85% in hikes over the next 5 meetings).

At Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s previous post-FOMC press conference (on 4 May 2022), he responded to a question about the possibility of hiking rates by 0.75% at the June meeting that the committee “weren’t actively considering 0.75% hikes”. However, 6 weeks later, in the lead-up to the most recent meeting, investors were convinced that there would not only be a hike of 0.75% at the June meeting but another one of a similar size at its subsequent meeting in July (followed by a couple of 0.5% rate hikes at the subsequent two meetings).

Figure 1: Investor expectations going into the June FOMC meeting

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

For context, throughout the past 50-odd years (going back to January 1971), the Fed has hiked rates 135 times and c. 80% of those hikes have been 0.5% or less. You have to go back to November 1994 to find a rate hike above 0.5% at any single Fed meeting (in that instance it was a 0.75% rate hike) and before that, the only hikes over 0.5% came before 1985. So, back-to-back 0.75% hikes are a pretty big deal!

The urgency this time around was a function of a few things:

- It is hard to find a time in modern Fed history when policy hikes have lagged the pick-up in inflation by as much (the Fed gave itself this wiggle room in a fairly recent amendment to its mandate in August 2020 from “keeping inflation close to, but below 2%” to “keeping inflation at 2%, on average” – the nuance being that the latter allowed the Fed to run inflation above 2% for a while if it had been below 2% for a while).

- Inflation is at its highest level in 40 years.

- US rates are coming off an extremely low level (0%), meaning the Fed’s ability to reverse course and loosen monetary policy in the event of an economic meltdown is limited.

For many of us, the prospect of Fed rates at 4% seems almost inconceivable, given that we have had rates anchored at 0% for most of the past 14 years. Since December 2008, until the Fed hiked rates in March this year, we have had:

- Rates at 0% for c. 70% of the time.

- Rates never above 2.25%.

- 9 interest rate hikes (all at 0.25%) spread over 3 years (and 24 Fed meetings).

- Average US core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation of 1.7%, while headline CPI averaged 2.1%.

- Average US unemployment of 6.5%.

- Average US GDP growth of 1.6%.

However, the c. 14 years pre-GFC (global financial crisis) was a very different environment. The period from January 1994 to December 2007 had:

- Fed fund rates average 4.2% (a maximum of 6.5%, and a minimum of 1%).

- Average core US PCE inflation of 1.9% (and a maximum of 2.7%).

- Average US headline CPI of 2.6%.

- Average US unemployment of 5.1%.

- Average US GDP growth of 3.3%.

So, we do not have to go digging too deep into the history books to find a period of decent economic growth, stable inflation, and Fed rates that averaged above 4%. It is just hard to imagine that world right now, and certainly the transition back towards there has thus far been a pretty painful one!

Figure 2: Fed rates have rarely been much above 0% since the GFC, but 4%-plus was more the norm in the 14 years pre-GFC

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

At its meeting last week, the Fed met investor expectations with a 0.75% interest rate hike, essentially doubling the rate to 1.5%. There was no change in the Fed’s guidance to winding down the balance sheet, which started at the beginning of June at a rate of c. US$50bn/month and will ramp up to US$95bn/month by September.

We also got two other sets of information from the latest Fed meeting:

- Updated economic forecasts from the 18 Fed members (and the teams of economists they have working for them), which are released quarterly (at every second Fed meeting) and include details on the following:

The anticipated path that the Fed rate is likely to take, and here we note the following:

- For 2022, median expectations are for the rate to get to c. 3.4% by year-end (slightly behind market expectations of c. 3.6%).

- For 2023, median expectations are for the rate to get to c. 8% by year-end (i.e., continued hiking in 2023, which is at odds with market expectations that the Fed will need to start cutting rates in 2023, by c. 0.4%).

- For 2024, median expectations are for the rate to get to c. 4% by year-end (some rate cuts).

- Longer-term, most Fed members believe that a neutral rate (i.e., where monetary policy is neither supportive nor restrictive) should be 25%-2.5% (i.e., the current rate at 1.5% is still supportive!).

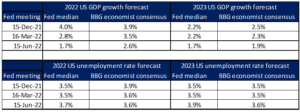

The anticipated path of economic activity, and here Fed members have become significantly more pessimistic over the past 6 months on the US’ economic prospects for 2022 and 2023:

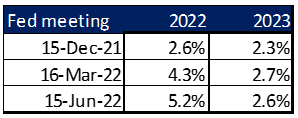

- 2022 inflation expectations have doubled:

Figure 3: Fed’s median US PCE inflation forecasts

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

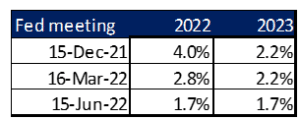

- 2022 Economic growth expectations have more than halved:

Figure 4: Fed’s median US GDP growth forecasts

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

- Unemployment will increase slightly in 2022 and again in 2023 (on this statistic it is very hard to find a period of increasing unemployment that was not swiftly followed by a recession).

Figure 5: Fed’s median US unemployment rate forecasts

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

- The Fed has become more pessimistic than Bloomberg consensus economist forecasts on economic activity over the past 6 months. Economists are still expecting the US economy to grow at 2.6% this year (the Fed expects 1.7% growth) and consensus economists are not yet anticipating an increase in the US unemployment rate (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: US Fed median GDP and unemployment forecasts vs Bloomberg consensus economists’ forecasts

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

- Some of Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s responses to questions posed by the media in the press conference are highlighted below:

- “We have to have price stability, we really do, if we don’t have price stability, the economy cannot work the way it is supposed to.”

- Wages are not principally responsible for the inflation we are seeing.

- It will take some time to get inflation back down.

- It is still possible to achieve a “soft-landing” (i.e., slow enough economic growth to get inflation under control, but not so much as to cause a recession), but it is not going to be easy “many factors that we do not control are going to play a significant role” including the war in Ukraine and supply-chain issues.

- We have experienced an extraordinary series of shocks. The Ukraine war, for example, could have effects “for years”. So, inflation is behaving differently.

- This is a highly uncertain environment – extraordinarily uncertain. If we see data going in a different direction, then policy will respond.

- A 75% move is “unusually large”, and such a move will not be common.

Market reaction

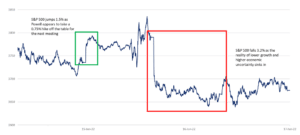

- With the market already priced for back-to-back 0.75% hikes, investors were largely sanguine about the initial hike announcement, but markets bounced strongly at question time when Powell suggested that another 0.75% at the Fed’s next meeting was not a done deal (a 0.75% move is “unusually large” and such a move will not be common), leaving the S&P 500 up 1.5% on the day (15 June 2022).

- But it was the moves on Thursday (16 June), the day after the meeting, that were the most eye-opening, with the S&P 500 falling by 3.2% on the day.

Figure 7: S&P 500 Index performance in the wake of the FOMC meeting

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

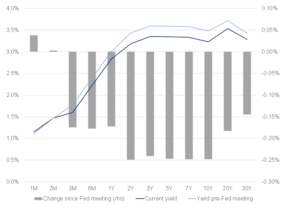

- In interest rate markets, investors are still expecting the Fed funds rate to end the year at 3.6% (largely unchanged from before the June meeting).

- US 10-year government bond yields have softened slightly (from 3.4% pre-meeting to 3.2%), perhaps discounting a slightly higher probability of a US recession.

Figure 8: US government bond yields dropped after the FOMC meeting

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

Conclusion

- The Fed seems to acknowledge that it will need to inflict some economic damage to get inflation under control, but that it will also require a healthy dose of good fortune on anything beyond its control (the war in Ukraine, supply chains, economic reopening) to achieve that without causing a US recession.

- Having fallen behind the curve in getting on top of inflation, the Fed is now looking to catch up and seems willing to err on the side of too much tightening (and the associated damage to US economic activity).

- It will be months before we see the bulk of the impact of the Fed’s current action on economic activity, so it is unlikely that we will know how successful the Fed’s current course of action is until much later this year, at best. In the interim, we are likely to see uncertainty (and the associated financial market volatility) persist.

- Financial markets seem priced for some level of uncertainty, but are not yet discounting a dire outcome:

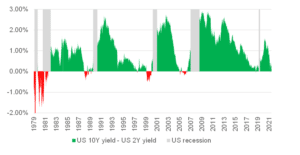

- The US yield curve is showing some signs of inversion beyond the 3Y point, but the traditional recession indicators (10Y–2Y/10Y–6M) are not yet flagging a recession:

Figure 9: The US government bond yield curve has not inverted yet

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

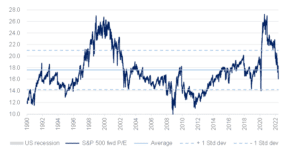

- S&P 500 valuations are now around 9% below their 30-year average, but still well above previous lows.

Figure 10: S&P 500 forward valuation metrics are slightly below the long-term average

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

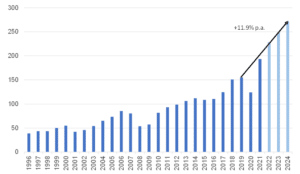

- Ratings are based on earnings that are still expected to grow fairly strongly for the next few years.

Figure 11: S&P 500 earnings are still forecast to grow strongly over the next few years despite slowing economic growth expectations

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg