As 3Q24 unfolded, global interest rates finally entered the long-awaited cutting cycle, signalling a significant shift in monetary policy for major economies like the US, eurozone, and UK. This has fed through to SA as well. After an extended period of aggressive rate hikes aimed at curbing inflation in the post-COVID-19 period, major central banks are pivoting towards easing financial conditions to support growth (and the labour market) in the face of moderating inflation and slowing economic activity. This moderation in inflation, particularly in DMs like the US, is driven by slowing employment and wage growth, along with stabilised energy prices. This has fuelled expectations that headline inflation may return to long-term targets by 2025.

However, persistent inflationary pressures in the services sector and rising maritime freight costs present ongoing risks to core inflation, complicating central banks’ monetary policy strategies. Additionally, geopolitical tensions and lingering supply chain disruptions threaten to derail the disinflationary momentum. In SA, where inflationary pressures and economic challenges are more pronounced, interest rate cuts will aim to provide relief amid sluggish growth. Therefore, as we transition into this new, less restrictive monetary policy environment, the outlook will be a crucial determinant for investors as 4Q24 progresses. The critical question is how low will rates go?

US: Is the Fed the hare of central banks?

When considering the US Fed through the lens of the tortoise and the hare analogy, it appears that the Fed embodies the hare’s role among central banks. Speculation had been rising that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) might dash out of the starting blocks with a bang – entering an easing cycle with a larger interest rate reduction than the usual 25-bp shifts. This was confirmed during the Fed’s latest Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting on 18 September, where it surprised consensus among economists by announcing a 50-bp reduction in the federal funds target range to 4.75%-5.00%.

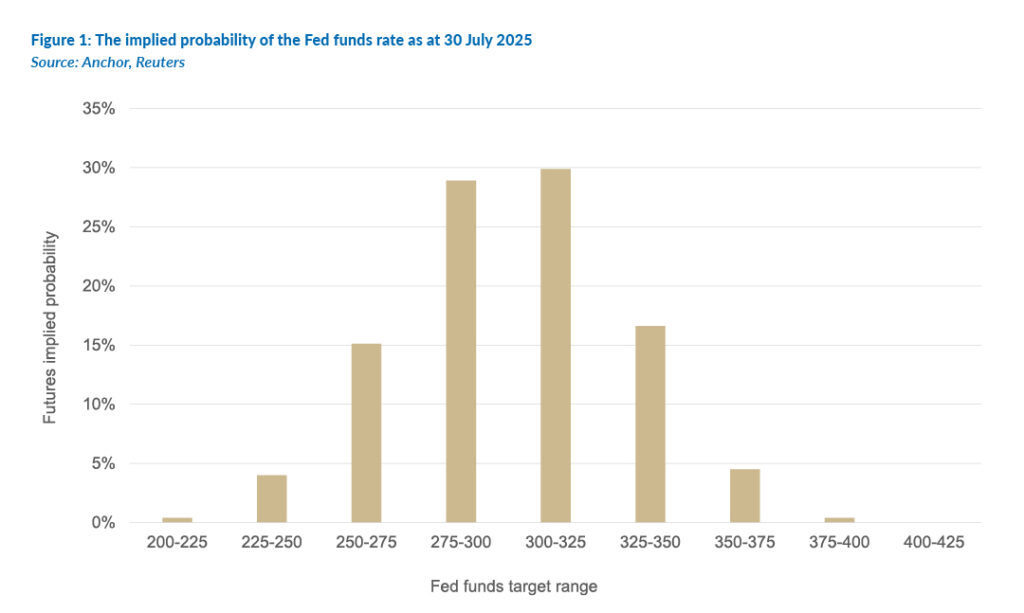

The MPC indicated this was not a “one and done” decision, as every member anticipates further rate cuts over the next year, according to the Fed’s updated dot plot, which reflects their future interest rate expectations. The emphasis of the meeting was seemingly more on said dot plot rather than the interest rate cut itself. The Fed estimates the long-term neutral interest rate to be just under 3%, consistent with previous communications, implying approximately 1.75% to 2.00% in potential cuts. Looking at the futures market, we can see a range of outcomes for the terminal federal funds rate (using the 30 July 2025 expected Fed meeting as the terminal level). While some market participants are trading on an implied probability of rates dipping into the low 2% range by mid-2025, most expectations (59%) centre on 2.75%-3.25%.

Notably, Fed governors have suggested that the journey to the neutral rate may occur faster than expected. Overall, in a sense, the meeting served as a lesson in risk management. The Fed does not foresee a sharp economic shock that would necessitate a loose policy stance. Yet, there is growing concern that maintaining current restrictive rates could hinder its employment mandate. Consequently, the FOMC used the 50-bp cut to signal its intention to reach a neutral policy level (where interest rates neither impede nor stimulate the US economy) more quickly. Notably, the median Fed member does not see the need to lower rates below the neutral level into an accommodative setting. Thus, while the Fed’s destination for interest rates is unchanged, it is accelerating the pace of cuts to reach that destination sooner. This could bode well for risk assets, as the Fed currently appears unconcerned about a US recession. Continued economic growth in the US will likely support equity markets, and it seems the “Powell put” is back, indicating the Fed has both the capacity and willingness to support US equities with further cuts if needed.

Eurozone: Walking a tightrope

In line with unanimous expectations, the ECB Governing Council decided at its September policy meeting to lower the key deposit rate by 25 bps to 3.50%. This marks the second step in its easing cycle, which began in June. As previously announced in March, the rate corridor was also adjusted, with both the main refinancing rate and the marginal lending rate lowered by 60 bps to 3.65% and 3.90%, respectively. These adjustments are intended to align with the normalisation of the ECB’s balance sheet and to guide short-term market rates as excess liquidity decreases. Consequently, this decision is more technical than a shift in the overall policy stance. ECB President Christine Lagarde emphasised that stability in the inflation outlook has given the ECB Governing Council greater confidence that inflation is moving towards the target, allowing for a reduction in policy restrictiveness.

Recent developments suggest that the ECB is not considering significantly changing its policy stance. The Council remains focused on data dependence rather than relying on individual data points as it navigates its monetary policy path. For now, it appears the ECB prefers to pursue gradual reductions in the degree of monetary policy restrictiveness, likely indicating 25-bp cuts during quarterly ECB staff projection meetings until the neutral rate is approached (currently fluctuating between a range of 2% and 2.5%).

Financial markets, however, are pricing in more aggressive cuts, anticipating the possibility of more than 25 bps of declines by year-end. We believe this scenario is unlikely. Where we align more closely with market sentiment is the potential for more than four policy rate cuts next year. However, growth and labour market data would need to disappoint the ECB’s forecasts again in order for this to materialise. The outlook remains uncertain; with the 2024 Paris Olympic Games boost fading, a weaker trajectory at the beginning of 2025 is certainly possible. If this occurs, the return to neutral may progress quicker than anticipated.

UK: Steady as she goes

In contrast to most DMs, the UK’s interest rate trajectory is an outlier after the Bank of England’s (BOE) latest rate decision. In the same month that saw the US, ECB, and SA cut rates, the BOE held rates steady at 5%. Once again, the decision was not unanimous, with one member advocating for an additional 25-bp reduction. This cautious decision reflected that the BOE is not in as fortunate a position as the US Fed regarding inflation. The latest August UK CPI printed at 2.2% – above the BoE’s target of 2%, with risks to the upside mounting. Whilst Inflation has fallen significantly since it hit 11.1% in October 2022 (the highest rate in 40 years), some parts of the UK economy, like the services sector, are still seeing more significant price rises.

More importantly, core inflation (which excludes the more volatile food and energy prices and serves as a critical indicator of underlying price pressures) remains sticky at 3.6%. A noteworthy takeaway from the September BOE meeting minutes highlighted that “for most members, in the absence of material developments, a gradual approach to removing policy restraint would be warranted.” This sentiment aligns closely with the market’s current expectation that the next rate cut is scheduled for November, followed by a steady path toward achieving a ‘neutral’ policy stance. Overall, the UK’s current economic landscape does not indicate an urgent need to rush toward this goal; instead, it supports a more measured approach.

When assessing the UK interest rate outlook, it is vital to consider the pace of quantitative tightening (QT). In its annual announcement, the BOE decided to lower its holdings of UK government bonds, known as gilts, by GBP100bn (US$133bn) over the next 12 months through a combination of active sales and the maturation of bonds. This decision aligns with the previous period, despite some expectations for accelerating the programme. The BOE’s balance sheet expanded significantly during the pandemic as it aimed to stimulate the economy, but it reversed course and initiated QT in February 2022.

Currently, the BOE is incurring losses on its QT programme, which taxpayers effectively subsidise since bonds are sold at lower prices than their original purchase costs. Despite this, BOE Governor Andrew Bailey argues that conducting QT is necessary now to create room for future quantitative easing (QE) or other monetary operations. This approach highlights the delicate balancing act the central bank must perform as it navigates economic recovery while managing its balance sheet effectively.

SA: If the US Fed is the hare of central banks, then the SARB is certainly the tortoise

Unlike the accelerating Fed, the SARB sees no point in rushing rates to lower levels, and instead, it believes that a gradual, data-driven approach is the most appropriate. Slow and steady will win the race for the SARB – the tortoise approach indeed. Against a steadily moderating inflationary backdrop, as expected, the SARB’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to lower the repo policy rate by 25 bps to 8% p.a. at its 19 September meeting, with the prime lending rate now sitting at 11.5%. In deliberating the policy stance, the MPC weighed three options – leaving rates unchanged, a 25-bp cut, and a more aggressive 50-bp cut. Ultimately, the committee agreed on a 25-bp reduction, concluding that a slightly less restrictive stance aligned with its goal of achieving sustainably lower inflation over the medium term.

This decision reinforced our long-held view that the MPC will avoid a sharp 50-bp cut, as the SARB typically favours gradual reductions to maintain market stability and predictability. This cautious approach reflects the SARB’s commitment to managing expectations and avoiding sudden market shocks. The central bank can adjust based on evolving economic conditions by adopting a data-dependent, incremental strategy. This method minimises the risks of large, rapid cuts, such as heightened market volatility or misaligned signals. It also ensures smoother transitions in financial markets, allowing for a more measured and adaptive response to inflationary pressures and economic performance.

Looking ahead, one key point from the latest SARB MPC statement is that its forecast sees rates moving towards neutral next year, stabilising slightly above 7%. This confirms our base case of 100-125 bps of cuts in this cycle. It is worth noting that the SARB’s Quarterly Projection Model (QPM) previously saw the repo rate ending at 7.25% but now signals a further 25-bp cut in 2025/2026. This will take the repo rate to a steady 7%, which aligns with our stated base case. Regarding market reaction, the specific timing or structure of these rate cuts seems relatively unimportant. Assuming the full magnitude of the reductions is ultimately delivered, markets are likely to respond in a relatively neutral manner, similar to the reaction seen shortly after the MPC announcement. This suggests that investors are more focused on the overall trajectory of monetary policy rather than the nuances of individual rate decisions.

As highlighted in Figure 2 below, we note a terminal expected rate of just below 7% (implying some market participants see rates dipping below 7% to 6.75% – this split is approximately 50-50). From the inferred forward rate agreement (FRA) data, we also highlight that market pricing expects, as we do, the gradual cutting cycle to persist, with no single meeting expected to deliver a greater than 25-bp cut. Given SARB MPC messaging on this topic, we are confident that the only deviations from this would be in the event of drastic changes to the underlying inflation, growth, or employment data metrics (with their relative importance in that order).

Conclusion

The direction of global central bank policy rates is downwards. The two key questions then are the rate of that decrease and the level to which central banks are willing to cut to stimulate economic growth. We foresee the pace of SA rate cuts being stable at 25 bps at a time, with a terminal rate likely to be 6.75%-7% (resulting in a prime rate of 10.25%-10.5%). The Fed is a more open-ended question, with a high probability of further 50-bp rate cuts and a likely terminal rate in the region of 2.75%-3.25%. With these movements, we will likely see a much more rapid deployment of global capital (with rates in the US nearly half their peak). This, in turn, should spark material global growth upticks in the outer years (2026 onwards). We also note that the expected comparative trajectories of rate cuts (approximately 200 bps for the Fed vs c. 125 bps for the SARB MPC) should support the rand and SA assets in general.