In the tempest of economic uncertainty, South Africa (SA) stands as a seemingly resilient protagonist, with the country’s sovereign credit ratings continuing to hold firm despite an increasingly difficult fiscal environment. Sovereign credit ratings are essentially assessments provided by credit rating agencies to gauge the creditworthiness of a country’s government and its ability to meet financial obligations, particularly debt repayments. As such, these ratings serve as indicators for investors and financial markets to assess the level of risk associated with lending money to a particular government. The major credit rating agencies, such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P Global), and Fitch, assign grades or scores to sovereign nations based on various economic, financial, and political factors.

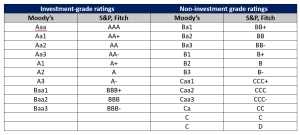

These ratings typically consist of letter grades or alphanumeric codes, ranging from high to low, with corresponding implications for risk. The highest ratings (e.g., AAA, Aaa) indicate a lower perceived risk of credit default, while lower ratings suggest higher risk. Sovereigns with Baa3/BBB- or higher ratings are considered investment grade. Sovereigns with Ba1/BB+ or lower ratings are regarded as non-investment grade (often called junk status). In addition to their investment grade, a rating agency can publish what they think the future looks like for a country’s debt. The outlook can be negative or positive. The factors influencing sovereign credit ratings include a country’s economic growth, fiscal policies, political stability, external debt levels, and overall economic resilience. These ratings are essential for governments to attract foreign investment, negotiate favourable borrowing terms, and manage their economic policies effectively.

Figure 1: Credit rating categories

Source: Moody’s, Fitch, S&P, Anchor

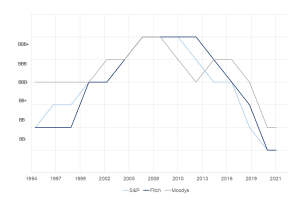

SA has seen a significant decrease in its credit quality from 2012 to 2022 due to various persistent issues, including high levels of public debt, political uncertainties, and structural economic challenges that have contributed to a complex fiscal landscape. The country’s struggle with low economic growth rates, unemployment, and inequality further compounds these difficulties. External factors, including complex global economic conditions and commodity price volatility, have added an additional layer of unpredictability. During the aforementioned period, SA’s credit rating fell from a BBB+ rating to a BB- rating. This translates to a drop from being on the brink of having high-grade credit quality to falling into speculative grade, i.e., junk status. Since then, SA has languished at the same rating levels.

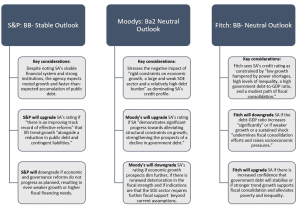

Whilst junk status is by no means a credit rating that any sovereign desires, it can be construed as somewhat of a positive that our ratings have not worsened further into junk territory – despite an increasingly difficult fiscal environment. While economic growth has not been forthcoming and concerns about SA’s growing debt burden remain rife, the key global rating agencies have noted that the country’s economic reform efforts thus far (such as the substantial investments in power generation and renewable energy) are expected to help, in part, support economic growth over the medium-term thus providing some level of buffer.

Figure 2: A summary of the sovereign credit rating (foreign currency) assessments of the major rating agencies at SA’s last formal rating reviews

Source: Moody’s, Fitch, S&P, Anchor

Figure 3: SA sovereign credit rating history

Source: Anchor, Reuters

Nonetheless, SA’s precarious fiscal situation has again come under the spotlight with the tabling of the 2023 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) on 1 November. As largely expected, FY23/FY24 revenues are forecast by the National Treasury (NT) to be around R56.8bn lower than projected in Budget 2023. This is primarily because of lower commodity prices, weaker global growth, increased loadshedding and the various logistical constraints that have weighed heavily on mining sector corporate tax collections. The budget deficit is now expected to come in at 4.9% of GDP for FY23/FY24, with debt projected to stabilise at 77.7% of GDP in FY25/FY26, compared to 73.6% in the 2023 Budget. It is worth pointing out, however, that said fiscal slippage does not yet equate to further credit rating downgrades – indeed, in the first formal credit rating review since the MTBPS, on 17 November, S&P affirmed its rating for SA (maintaining a stable outlook). Nonetheless, our sense is that the various key rating agencies will keenly await the Budget next year.

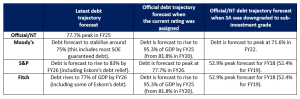

The table below compares the three major rating agencies’ latest forecasts for the SA government’s debt-GDP trajectory to the official forecasts at the time of their last downgrade and when they downgraded SA to sub-investment grade. It is worth highlighting that for Fitch and Moody’s, the trajectory is significantly lower (nearly 20 ppts) than when SA’s current rating was assigned. It is higher than when S&P assigned its current rating but still lower than S&P’s latest debt forecast (when the rating was preserved).

Figure 4: The latest debt-GDP forecasts vs debt forecast at junk status downgrade

Source: Moody’s, Fitch, S&P, Anchor

At the end of the day, addressing SA’s structural economic constraints is imperative for enhancing its credit rating outlook. Persistent challenges such as high unemployment, economic inequality, and slow GDP growth contribute to an intricate web of issues that affect the country’s creditworthiness. To attract investment and demonstrate fiscal responsibility, SA must prioritise structural reforms, including improvements in labour market dynamics, regulatory frameworks, and public sector efficiency. A concerted effort to address these constraints can lead to increased economic resilience, fostering a more favourable environment for sustainable growth. By demonstrating a commitment to comprehensive and effective economic reforms, SA can enhance its credit rating outlook, making it more appealing to investors and facilitating access to international capital at favourable terms.