The mid-March expulsion of SA’s ambassador to the US, Ebrahim Rasool, marks a new flashpoint in the already complicated and often contentious relationship between Washington and Pretoria. Rasool’s recent public remarks criticising the Trump administration ignited this diplomatic fallout, highlighting the fragility of the already strained US-SA ties. Historically, the relationship between the two nations has been shaped by fundamental policy disagreements, often rooted in more profound ideological and geopolitical divergences. While cooperation has persisted (particularly in trade, investment, and development assistance), these tensions have repeatedly placed the two countries on opposite sides of key global issues.

With the growing diplomatic strain and potential economic repercussions, the critical question is whether this episode will cause a lasting rupture or serve as a catalyst for recalibrating their strategic engagement. At the core of this relationship are three key channels linking SA to the US: trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio flows, and US foreign aid. Understanding these economic ties is essential to assessing the broader implications of the current standoff.

Channel 1: Trade at a crossroads – assessing SA’s economic exposure

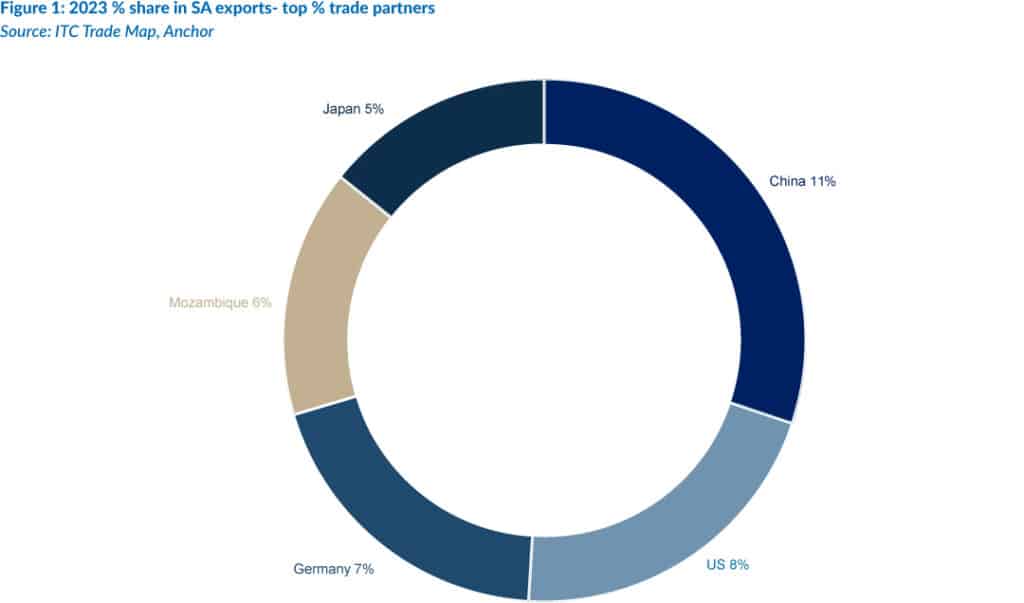

Trade is a critical pillar of SA’s relationship with the US, and while the US is a key export destination, SA’s exposure is broadly in line with other BRICS economies. SA exports to the US account for 9% of total exports, a meaningful figure that mirrors Brazil and China’s trade dynamics. India, in contrast, faces a higher degree of risk from potential tariff threats, while Russia, due to sanctions, has minimal trade engagement with the US. However, beyond the share of exports, the true measure of economic vulnerability lies in how dependent a country’s overall economy is on trade with the US.

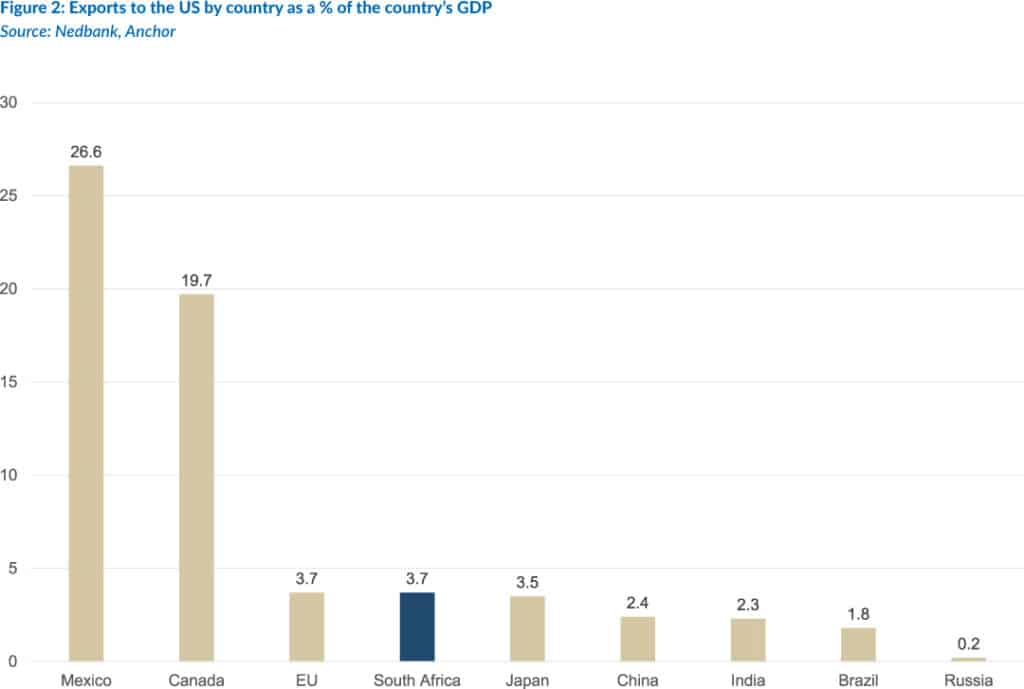

In this context, the percentage of a nation’s GDP tied to US exports is crucial in assessing potential economic shocks. For example, Mexico’s exports to the US represent a staggering 26% of its GDP, making it highly exposed to any trade disruptions. In contrast, SA’s exports to the US account for just 3.7% of its GDP, a level comparable to the EU. While this suggests that SA is more vulnerable than other BRICS members, its exposure remains moderate. Ultimately, unless trade with the US were to collapse entirely—a highly unlikely scenario—the economic impact on SA would be significant but not catastrophic.

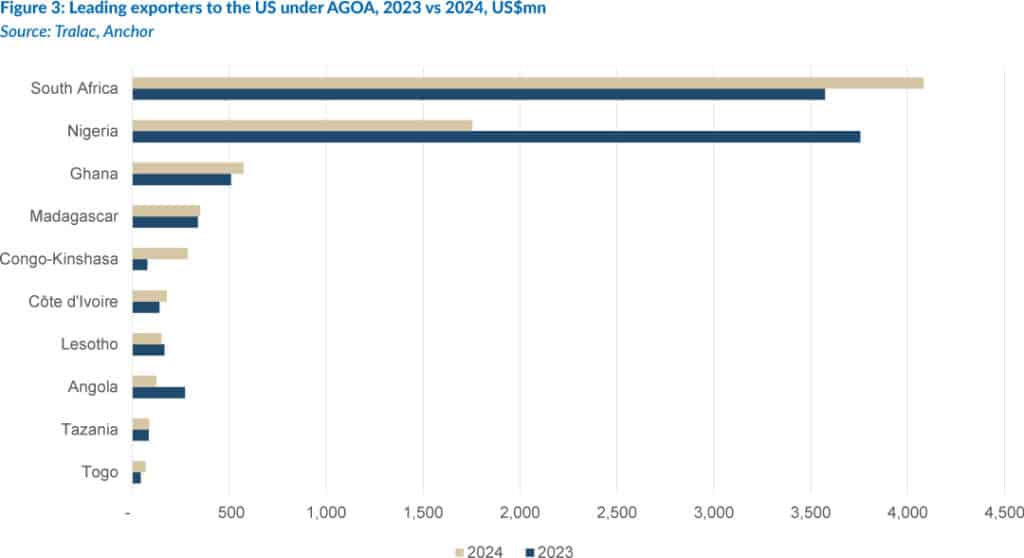

A key factor in SA’s trade relationship with the US is the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a landmark piece of US legislation enacted in 2000 to enhance economic ties with Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). AGOA grants eligible African nations preferential, duty-free access to the US market, supporting economic growth, job creation, and poverty reduction. While AGOA is a cornerstone of African trade policy, its overall significance to the US economy is relatively small. As of 2023, imports under AGOA accounted for just 0.3% of total US imports. Even if the US were to impose a 25% tariff on all AGOA imports, the estimated revenue gain of US$2.5bn would represent a mere 0.2% of total US government revenue.

For African nations, however, AGOA plays a much more critical role. On average, one-third of all exports from AGOA countries to the US are conducted under the agreement, and for SA, this share stands at 25%. In 2023, SA was the second-largest AGOA exporter behind Nigeria and the leading exporter of non-crude oil products. Its AGOA-eligible exports, valued at US$3.6bn, span a diverse range of goods, including vehicles, yachts, precious jewellery, chemicals, and citrus fruit.

However, AGOA’s true impact extends beyond GDP metrics; a significant contribution lies in employment. Studies by SA’s Department of Public Works estimate that AGOA has created approximately 350,000 direct and 1.3mn indirect jobs across SSA. SA accounts for 62,395 of these jobs—equivalent to 0.4% of the country’s employed population.

Trade tensions have escalated further beyond just SA’s borders, following US President Donald Trump’s announcement of sweeping new worldwide tariffs on goods imported into the US. As of 5 April, a universal 10% tariff was implemented, with a second, more severe round of reciprocal tariffs scheduled for 9 April. However, less than 24 hours later, these were paused for 90 days to allow for further negotiations. Simultaneously, the administration raised tariffs on Chinese goods to 125% in response to China’s earlier move to impose 84% tariffs on US imports. While Trump maintained a broad 10% tariff on all US imports, the decision to pause the reciprocal tariffs reflected a degree of caution, likely aimed at avoiding a sharp blow to market sentiment. Although this reprieve may offer some support to markets, the escalating tit-for-tat trade war—marked by the US increasing tariffs on Chinese goods to 125% and China retaliating with 84% tariffs—continues to pose a risk, keeping global markets on edge. Regardless of the schematics of when these tariffs will formally be enforced (and at what eventual level), some important schematics are worth considering.

Once implemented, some goods will be exempt, with these exclusions particularly relevant to SA as they include platinum group metals (PGMs) and gold. Autos, auto parts, aluminium, and steel will also be exempt from the reciprocal tariffs, though these remain under significant strain due to existing Section 232 duties of 25%. The White House has published an extensive exemption list, including semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, copper, lumber, and energy products. However, several of these items are subject to separate investigations, leaving room for future trade action. Notably, the new tariffs apply solely to goods and not services. These measures will be stacked on top of the US’s most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariffs, which have already seen a 25% rise in duties on cars, steel, and aluminium.

Economically, tariffs tend to distort trade flows by pushing production away from the most efficient sources. In the current context, the immediate concerns centre on volatility, policy uncertainty, inflationary pressures and potential drag on GDP growth. While exporters, wholesalers, and retailers may absorb some of the increased costs—and export rerouting could soften inflationary effects—a notable rise in inflation is still expected. Higher prices will reduce real incomes and suppress consumer spending, potentially slowing the US economy. In the medium term, this could feed into wage inflation as workers seek to maintain their purchasing power.

For SA, the new trade regime poses significant challenges. Although the country exports a diverse range of products to the US, these are highly concentrated in a few sectors. According to US Census Bureau data, precious metals and stones accounted for 57% of SA’s exports to the US in 2024. These have primarily entered duty-free under AGOA, and most will remain exempt—except diamonds and jewellery.

Exports of vehicles, aluminium, and steel will continue to be subject to 25% tariffs under Section 232. At the same time, pharmaceuticals and various other goods on the exemption list comprise a relatively small share of total exports. Nevertheless, assuming no change in trade patterns would likely overstate the effective tariff burden, as many SA exporters could find themselves priced out of the US market under the new rules. The 30% US import tariff presents a significant obstacle to SA’s trade balance and broader economic trajectory, with profound implications for key industries, the national budget, and fiscal planning.

Channel 2: Investment and influence – the role of FDI

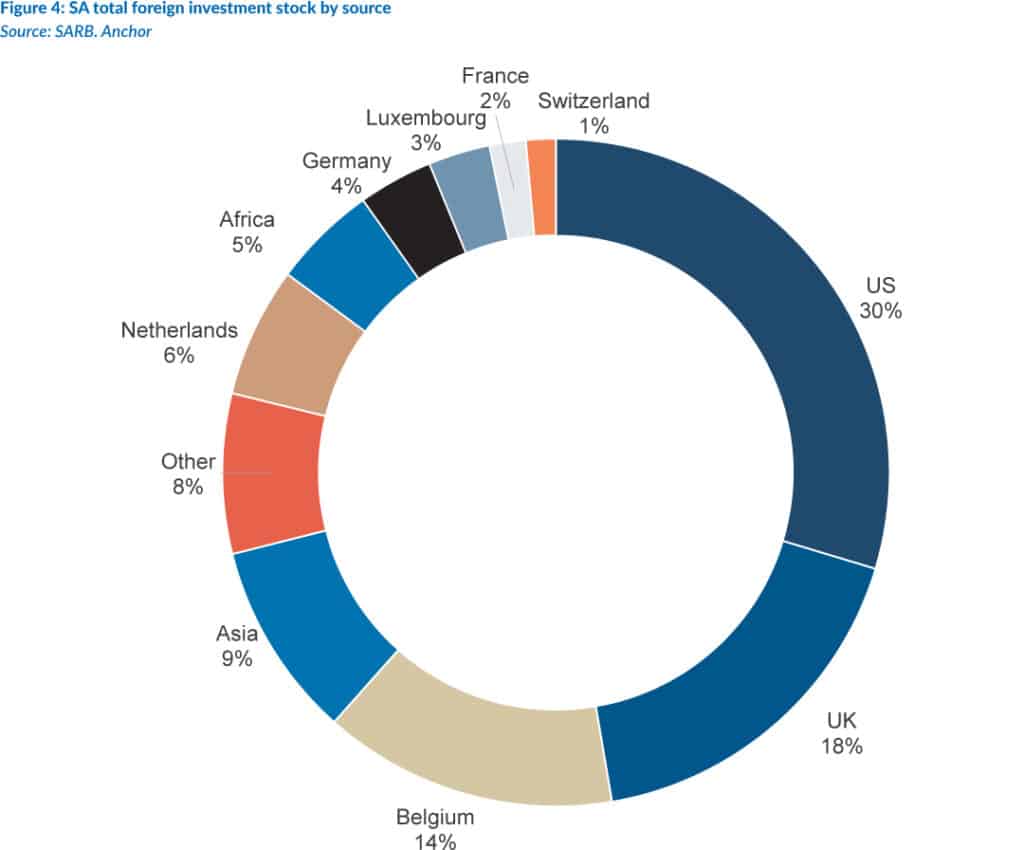

While trade tariffs currently appear to be the more favoured tool of the Trump administration to exert pressure on trading partners, the US role as a major investor in SA presents an even greater potential point of leverage. Beyond trade, US financial flows into South Africa are critical in shaping the country’s economic stability, capital markets, and investor sentiment. An analysis of foreign investment patterns reveals that while SA’s largest stock of FDI comes from the UK, the Netherlands, and Belgium (collectively surpassing R1.1trn in 2023), these figures are overshadowed by the scale of US portfolio investments. Total US portfolio holdings in domestic stocks, bonds, and funds reached R1.7trn, making the US the single largest investor in the country.

When factoring in derivatives and other financial instruments, US investment in SA stood at nearly R2trn in 2023, equivalent to 29% of SA’s GDP. This places the US ahead of all other countries, with the UK following in second place with R1.17trn in total investment. US direct investment in SA is concentrated in key sectors, including manufacturing, finance and insurance, and mining. Meanwhile, portfolio investments reflect US institutional and retail holdings in SA-listed equities and fixed-income instruments. This deep financial entanglement means that any deterioration in diplomatic relations—especially if accompanied by punitive trade measures—could have significant spillover effects on SA financial markets.

Channel 3: Aid and uncertainty

According to data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), SA received just over US$1bn in total foreign aid and assistance in 2022, with nearly half of this funding coming from the US. The bulk of US aid was directed toward HIV/AIDS treatment through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Other major donors included France (US$343mn), the Global Fund (US$152mn), and the UK (US$28mn). On his first day in office, Trump imposed a 90-day freeze on foreign development aid, which was later extended to include a complete suspension of US assistance to SA—including the US$6.5bn p.a. allocated to PEPFAR. The abrupt halt in funding has already had a significant impact on SA’s healthcare system, particularly in the treatment of HIV/AIDS.

PEPFAR previously accounted for 17% of SA’s US$400mn annual HIV budget and played a crucial role in providing life-saving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to 5.5mn people. The sudden withdrawal of this support has severely strained health services, leaving many patients without access to essential medication. Experts warn that the disruption in HIV treatment could have catastrophic long-term consequences, with some estimates suggesting that the aid freeze could result in over 500,000 deaths in SA over the next decade. Beyond the immediate health crisis, suspending US assistance could weaken SA’s broader public health infrastructure, increase pressure on domestic health budgets, and exacerbate socio-economic challenges. The loss of funding threatens not only individual lives but also the country’s progress in combatting the HIV/AIDS epidemic, potentially reversing years of gains in prevention and treatment efforts.

The expulsion of Rasool marks a significant escalation in the increasingly strained US–SA relationship, highlighting the tangible economic and institutional risks at stake. While dramatic rhetoric and confrontational policies have become hallmarks of the Trump administration, the decision to expel a diplomat remains serious, underscoring the depth of the current diplomatic rift.

This latest action must be seen in the broader context of sustained US pressure on SA since Trump’s return to office—including allegations around land confiscation and support for Iran’s nuclear programme, the withdrawal of US$1bn in Just Energy Transition Plan (JETP) funding, and persistent social media attacks from senior US officials and influential voices such as Elon Musk. The US’s recent imposition of sweeping global tariffs has delivered a direct economic blow to SA. Recent IMF modelling suggests a 0.35 ppt hit to the country’s GDP growth this year due to the new tariffs. As a result, Anchor’s projected growth has been revised lower to just 1.3%—before accounting for any possible fallout from SA’s increasingly fractious politics within the GNU. The 30% US import tariff now represents a major obstacle to SA’s trade balance and economic trajectory, with exporters facing the risk of being priced out of the US market.

These developments underscore that Washington’s threats are not merely symbolic but are already translating into significant economic consequences for SA. The immediate risks include rising inflation, reduced real incomes, and a potential slowdown in GDP growth, compounded by a highly concentrated export profile and an already strained fiscal environment.

With the increasingly fraught global trade environment and the possibility of targeted sanctions on SA entities or individuals looming, the stakes are higher than ever. The US remains a key trading partner, investor, and aid contributor. Any further deterioration in this relationship could reverberate through SA’s financial markets, stifle economic growth, and disrupt critical public health programmes. As tensions deepen, SA must carefully navigate this challenging diplomatic landscape—balancing its strategic interests while working to mitigate the growing economic fallout.