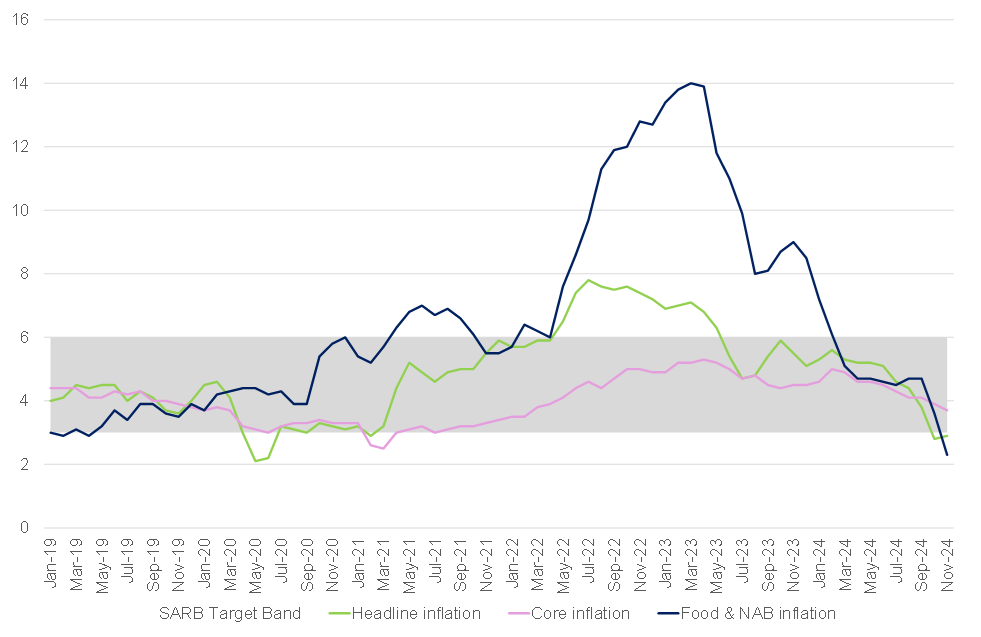

November inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), came in at 2.9% YoY, up slightly from October’s 2.8% YoY print but remaining below the South African Reserve Bank’s (SARB) target range of 3%-6%. The central bank cut its main lending rate for the second consecutive meeting last month, following October’s inflation reading, which marked the first time since February 2021 that inflation fell below the target range. A slower pace of deceleration in fuel inflation primarily drove the modest uptick in headline consumer prices in November. This upward pressure was partially offset by a notable decline in the inflation rate for food and non-alcoholic beverages, which has been a key driver of household expenses in recent months.

Core inflation, which excludes the more volatile components of food and energy to capture underlying inflationary pressures better, eased to 3.7% YoY in November from 3.9% in October. This decline in core inflation reflects subdued economic demand dynamics shaped by the prolonged impact of contractionary monetary policy. Additionally, limited exchange rate pass-through effects and restrained consumer spending further tempered inflationary pressures. Retailers also appear to be absorbing increased utility costs — including electricity and water — rather than passing these on to consumers. This suggests a challenging environment for businesses and highlights the financial pressures many households are currently experiencing.

Figure 1: SA inflation, YoY % change

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

Annual inflation for food and non-alcoholic beverages (NAB) continued its sharp decline in November, easing to 2.3% from 3.6% in October. This represents the lowest inflation rate for the category in nearly 14 years – last seen in December 2010 when it stood at 1.6%. Notably, eight out of the 11 food and NAB subcategories registered slower inflation rates, including key staples such as vegetables, milk, eggs, and cheese, as well as hot beverages, bread and cereals, cold beverages, meat, sugar, sweets and desserts, and the miscellaneous “other” food group. While fish prices held steady with no change in inflation, two categories—oils and fats and fruit—saw steeper price increases, underscoring some lingering pressures in specific segments of the food basket. The annual inflation rate for bread and cereals, a major household staple, moderated further, cooling to its lowest level in nearly three years. Critical items such as brown bread, white bread, maize meal, cold cereals, pasta, and rice all recorded lower inflation rates. However, inflation picked up for select items, including samp and hot cereals, reflecting some variance within the group.

Meanwhile, milk, eggs, and cheese inflation fell to its lowest rate in nearly five-and-a-half years. A standout development was the shift in egg prices, which moved into deflationary territory in November, dropping to -3.7%. This marks a dramatic turnaround from November 2023, when egg inflation reached a staggering 39.9%, severely straining household budgets. The decline in bread and cereal inflation reflects the waning impact of El Niño weather patterns, which had previously disrupted grain supplies and increased feed costs, indirectly driving up meat prices. Similarly, the easing of earlier weather-related disruptions in the vegetable category, notably the black frost that affected tomatoes and potatoes earlier this year, has contributed to the broad-based moderation in food inflation. These developments underscore an encouraging trend of price relief for SA households, particularly as food inflation has been a persistent driver of financial strain throughout much of 2024. However, localised pressures in specific categories highlight the continued need for vigilance in monitoring food price trends.

Figure 2: Food and beverage products that recorded the most significant annual and monthly price increases in November

Source: Stats SA

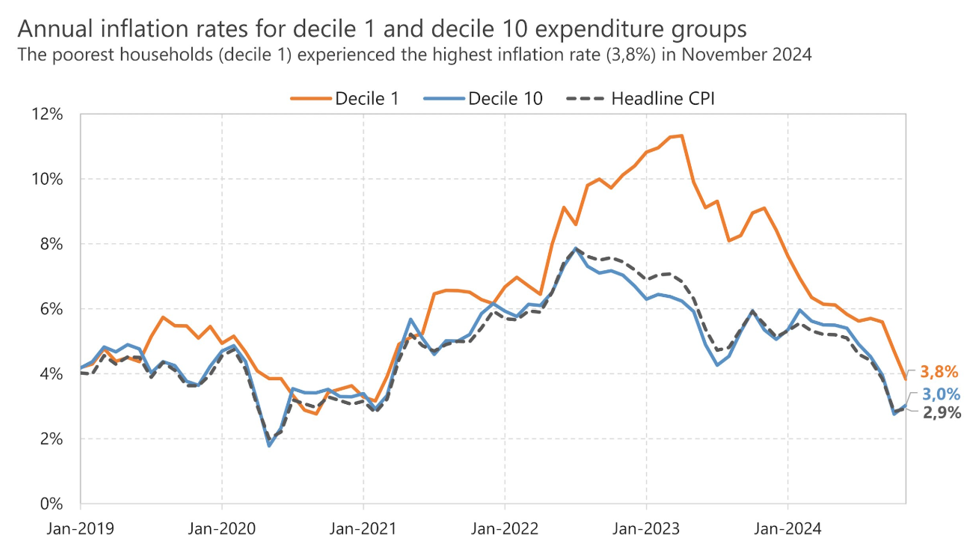

An intriguing aspect of SA’s inflation dynamics is how Stats SA calculates inflation rates across ten distinct expenditure categories, shedding light on the varying impacts of inflation on different socio-economic groups. These categories offer a nuanced view of how inflation affects households based on income and spending patterns. Since January 2022, the poorest households (decile 1) have consistently borne the brunt of inflationary pressures. Inflation for this group peaked at a staggering 11.3% in April 2023, primarily driven by sharp increases in the prices of essential goods such as food and energy, constituting a significant portion of their expenditure. While the inflation rate for these households has eased significantly to 3.8% in November 2024, it remains the highest among all expenditure categories, underscoring the disproportionate vulnerability of low-income households to price shocks.

In contrast, the wealthiest households (decile 10) experienced a more moderate inflationary impact, with an annual rate of 3.0% in November 2024. This is marginally above the headline inflation rate but significantly lower than the rates experienced by the poorest households. Higher-income groups tend to spend a smaller proportion of their budgets on necessities like food and energy and more on discretionary items, which often exhibit less price volatility. The disparity in inflation experiences highlights the unequal burden of rising prices across socio-economic groups. Even a modest rise in inflation can significantly erode purchasing power for poorer households, given their limited financial buffers and reliance on essentials. Conversely, wealthier households are better positioned to absorb cost increases, benefitting from diversified spending patterns and greater financial resilience.

Figure 3: Annual inflation rates for different income groups

Source: Stats SA

The latest CPI reading, which remained below the 3% threshold, took the broader market by surprise. While the data underscores the persistent softness in inflationary pressures, it is unlikely to prompt the SARB to adopt deeper or more aggressive interest rate cuts despite ongoing pressure from the market to do so. Although the subdued inflation print keeps real interest rates firmly in restrictive territory — a condition that might traditionally argue for more substantial monetary policy easing — the SARB’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has repeatedly emphasised a cautious approach. This preference for a measured easing cycle reflects its commitment to mitigating potential risks, including volatility in the rand, which is particularly sensitive to shifts in investor sentiment.

Global economic policy uncertainties and heightened geopolitical tensions remain critical upside risks to inflation. These factors could exert pressure on oil prices, translating into higher fuel costs domestically. Similarly, risks to food prices persist, driven by concerns over poor harvests, locally and in key global agricultural markets, potentially stemming from adverse weather events such as El Niño. Given these dynamics, we believe the SARB will likely maintain its current trajectory of gradual rate reductions, opting for 25-bp cuts at a time. This incremental approach allows the central bank to navigate the balancing act between supporting economic growth and guarding against inflationary shocks.

The SARB has indicated that it views such cautious adjustments as the path toward achieving a neutral interest rate — a level that neither stimulates nor restrains economic activity. In our view, the prime lending rate, currently at 11.25%, is expected to decline to 10.50% by June 2025. This forecast reflects the SARB’s deliberate policy stance to ensure a sustainable alignment between inflation and growth while addressing potential external risks and domestic vulnerabilities.