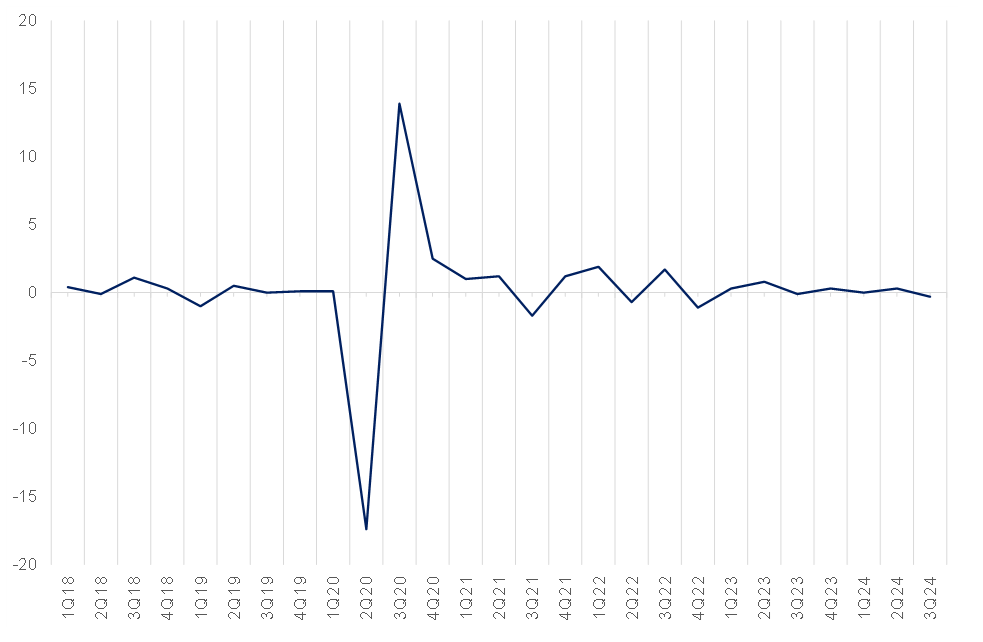

Despite an improvement in economic sentiment following the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU), South Africa’s (SA) economy unexpectedly contracted in 3Q24. Gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 0.3% QoQ, starkly contrasting the revised growth of 0.3% recorded in 2Q24. This downturn underscores persistent challenges within the country’s economic landscape. The contraction was primarily driven by a significant agricultural sector slowdown, which emerged as the main drag on production (supply side). Additionally, other key sectors, including transport, trade, and government services, also contributed to the economic decline. On the expenditure (demand) side, the economy faced setbacks due to declining imports, exports, and government consumption, reflecting broader weaknesses in domestic and external demand.

The implication of this weak third-quarter performance for SA’s overall economic outlook is of particular concern. The subdued GDP data casts doubt on the South African Reserve Bank’s (SARB) modest full-year growth projection of 1.1% for 2024. While there is hope for accelerated growth in the final quarter (4Q24), the current trajectory suggests that meeting the target will be challenging. This underscores the urgent need for robust interventions to address structural issues and boost economic resilience.

Figure 1: SA GDP growth QoQ % change

Source: Anchor, Stats SA

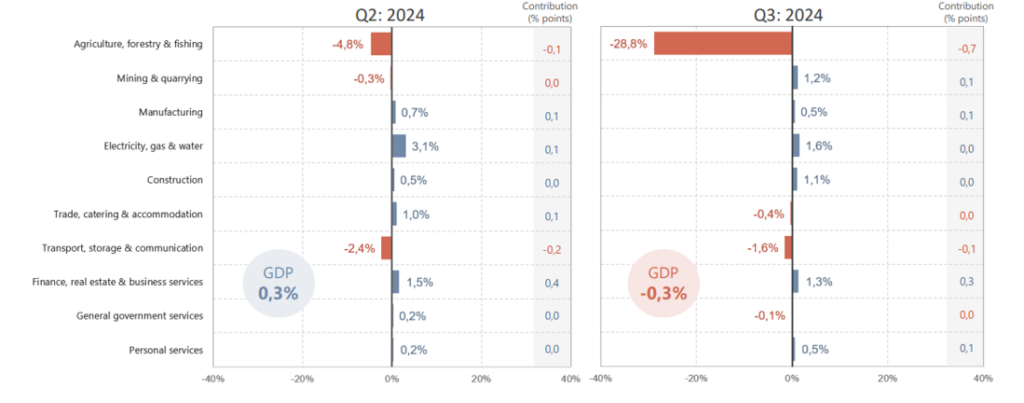

Breaking down the latest GDP data at a sectoral level on the production side of the economy reveals a mixed performance, with notable challenges and pockets of resilience. Agriculture suffered its second consecutive quarterly decline, plunging by a staggering 28.8% QoQ in 3Q24. This made it the largest drag on GDP, reducing overall growth by 0.7 QoQ. The industry faced a tough quarter, heavily impacted by drought conditions that significantly disrupted the production of field crops such as maize, soybeans, wheat, and sunflower. Adverse weather also hindered the harvest of subtropical and deciduous fruits and vegetables in various regions, compounding the sector’s woes. Other industries also experienced notable contractions. The transport, storage, and communication sector emerged as the second-largest negative contributor, driven by declines in land transport and transport support services. Similarly, the trade, catering, and accommodation industry faced setbacks, weighed down by disappointing performances in wholesale trade, motor trade, and the restaurant, fast food, and catering sectors. The general government sector also contracted due to lower employment levels in the civil service, adding to the economy’s broader challenges.

Despite the challenges, there were also bright spots in 3Q24, showcasing resilience in some sectors. The finance industry emerged as a significant positive contributor to GDP, buoyed by robust activity in banking, insurance, real estate, and other business services. The electricity, gas, and water supply sector expanded for a second consecutive quarter, supported by increased electricity generation and consumption. Mining also posted gains, driven by stronger manganese and chromium ore production. Manufacturing showed resilience, with iron, steel, and machinery production providing much of the upward momentum. The construction sector recorded its second straight rise, growing by 1.1%—its largest increase in two years. This growth was primarily driven by construction works, supported by activities related to non-residential buildings. These pockets of resilience in the economy provide a glimmer of hope amidst the challenges.

Figure 2: Comparing sector growth rates in 2Q24 and 3Q24, QoQ % change

Source: Stats SA

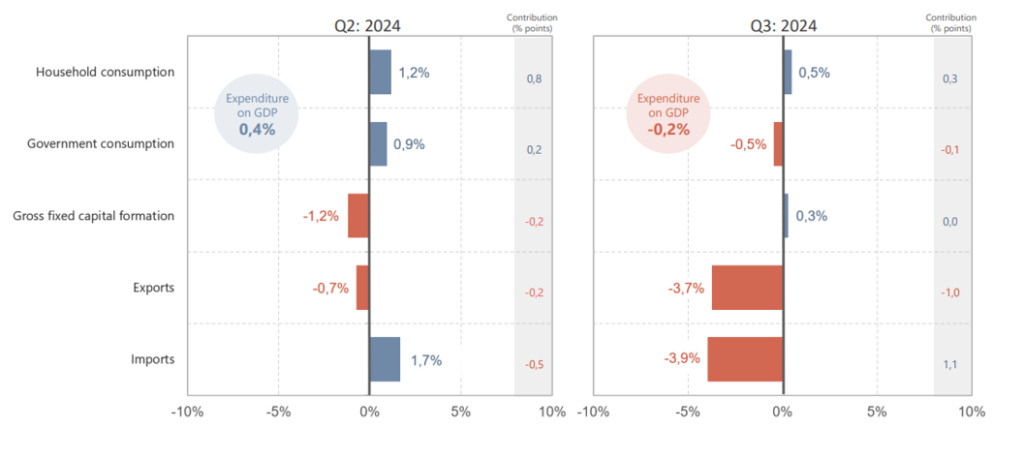

It is important to note that Stats SA also measures the expenditure side of GDP, indicating total demand in the economy. On the expenditure side of the economy, 3Q24 saw notable declines in exports and imports, signalling weaker international trade activity. Exports fell by 3.7% QoQ, marking the biggest drop in three years. This decline was primarily attributed to reduced trade in pearls, precious and semi-precious stones, precious metals, lower exports of vehicles and transport equipment (excluding large aircraft), chemical products, base metals and related articles, and machinery and electrical equipment. The broad-based weakness across these categories reflects subdued global demand and possibly logistical challenges. Imports mirrored this downward trend, contracting by 3.9% for the quarter. The decline in imports was driven by reduced demand for vehicles and transport equipment (excluding large aircraft), mineral products, vegetable products, base metals and their articles. The weakness in imports suggests a combination of reduced domestic demand for high-value goods and cost-saving measures amid economic uncertainty.

Amid these trade challenges, household consumption expenditure (HCE) provided a modest counterbalance, rising by 0.5% during the quarter. Consumers spent more across most product categories, driven by a slight recovery in disposable income and improved consumer sentiment in certain areas. However, expenditure on transport notably decreased, likely reflecting elevated fuel prices, higher interest rates, or reduced mobility. The mixed performance on the demand side underscores persistent vulnerabilities in international trade and domestic consumption. While household spending offers a glimmer of resilience, the contraction in trade activity highlights the need for policies that enhance export competitiveness and stabilise import-dependent sectors. Strengthening these demand-side components will be critical to driving a more sustainable recovery.

After four consecutive quarters of decline, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) recorded a modest recovery, expanding by 0.3% QoQ. This growth was primarily driven by increased investment in other assets, construction works, machinery, and equipment. While this marks a positive shift, the details reveal a more nuanced picture. The uptick in investment was mainly attributable to spending by the general government and public corporations, with private business enterprises (traditionally the largest contributors to investment) continuing to decline. This persistent weakness in private sector capital expenditure raises concerns about the sustainability of the overall recovery in investment activity. A closer look at the data highlights the extent of the challenge. Excluding machinery and equipment (a category that includes significant spending on renewable energy projects), private capital expenditure has plummeted, now sitting 30% below its pre-pandemic levels. This underscores the slow pace of recovery in broader private investment, even as specific sectors like renewable energy show signs of resilience. Encouragingly, the RMB/BER Business Confidence Index (BCI) improved further in 4Q24, signalling a potential turnaround in private sector investment. However, given the low base from which capital expenditure is starting, it will take time and sustained confidence to drive a meaningful recovery. Addressing structural barriers to private investment and fostering a more conducive business environment will be critical to accelerating this process.

Figure 3: QoQ % change in expenditure components and contribution to expenditure on GDP

Source: Stats SA

Notably, excluding the agricultural sector, SA’s economy would have grown by 0.4% in 3Q24, as most other industries performed largely in line with expectations. However, the sharp decline in agriculture highlights the vulnerability of the broader economy to sector-specific shocks. Nonetheless, the overall GDP contraction in 3Q is a significant setback for the GNU’s pledge to prioritise economic growth. Over the past decade, the country’s economic expansion has averaged less than 1% p.a., consistently trailing population growth. This stagnation emphasises the pressing need for structural reforms and targeted interventions to drive sustained and inclusive growth.

Moreover, the average SA consumer is, in fact, becoming poorer – the latest data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) indicates that SA’s GDP per capita is now below the average for emerging economies – and at about the same level as in 2005. According to IMF data, SA’s GDP per capita dropped from US$6,680 in 2022 to US$6,190 in 2023 – far below the record-high of US$8,800 recorded in 2012. Additionally, the 2023 domestic GDP per capita is below the US$6,450 average for emerging and developing markets. Notably, this is the same level of GDP per capita as in 2005. Simply put, SA’s expanding population growth, the weakness of the rand and the minimal economic growth means that the country’s population has been getting poorer in real terms. Moreover, in the domestic economy, material job creation has only occurred when GDP growth approaches 3% p.a. Thus, the economy is simply not growing at an adequate rate to sustainably boost long-term employment prospects for South Africans.

Despite the significant challenges facing SA’s economy, the positive performance of certain key industries underscores opportunities for targeted interventions to stimulate growth and build resilience. Sectors such as finance, mining, manufacturing, and electricity generation have shown encouraging signs of recovery, demonstrating their potential to contribute meaningfully to the broader economic revival. By prioritising reforms and investments in these areas, the government and private sector can create a foundation for more sustainable growth. For example, enhancing infrastructure, fostering innovation, and addressing regulatory bottlenecks could amplify gains in these industries. Moreover, promoting partnerships between the public and private sectors could unlock additional resources and expertise, further strengthening the economy. As the country navigates its way through persistent headwinds, leveraging these opportunities will be essential to drive inclusive growth, improve employment prospects, and increase economic resilience in the months ahead.