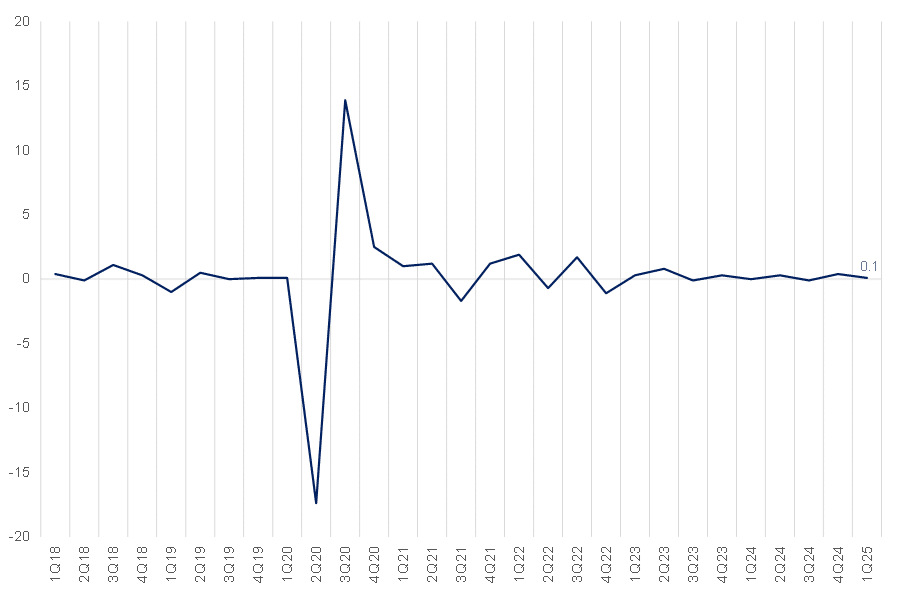

The South African (SA) economy managed to just stay afloat in 1Q25 as GDP rose by a meagre 0.1% QoQ on a seasonally adjusted basis, following a revised 0.4% increase in 4Q24. On the production (supply) side, only four out of ten industries recorded growth, with agriculture contributing the most to the modest upward momentum. On the expenditure (demand) side, household consumption, stronger export performance, and a drawdown in inventories helped keep the local economy in positive territory.

The weak GDP print reflects a subdued economic environment, weighed down by persistent structural challenges and low business confidence, which continues to dampen investment prospects. Domestically, political uncertainty was elevated during the quarter, driven by concerns around the stability of the Government of National Unity (GNU). On the global front, trade conditions remained fragile amid ongoing tariff volatility, further complicating the economic landscape.

Figure 1: SA GDP growth QoQ % change

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

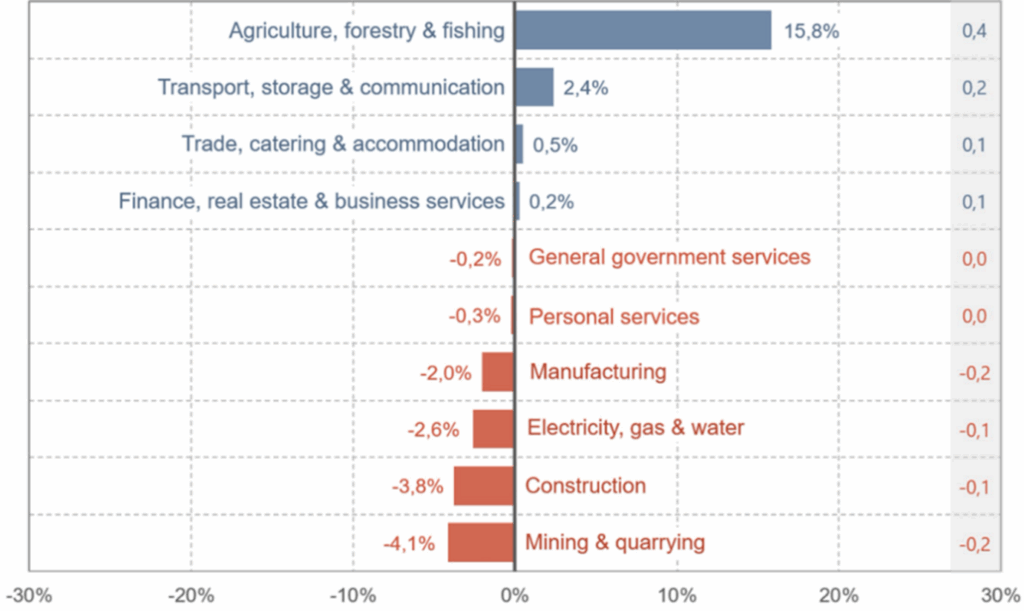

On the supply side, the agricultural sector had a remarkable quarter, surging by 15.8% QoQ, contributing 0.4 ppts to GDP growth. This impressive expansion was driven by favourable rainfall, with horticulture leading the gains, while animal production also performed well. Notably, without agriculture’s contribution, GDP would have contracted by 0.3% QoQ. The transport, storage, and communication sector was the second-largest positive contributor, growing by 2.4% QoQ. Gains were recorded across land transport, air transport, and transport support services. Trade, catering, and accommodation expanded by 0.5%, reflecting stronger consumer activity. Positive contributions also came from retail trade, motor trade, accommodation, and food and beverages.

As expected, financial and real estate services continued their positive streak, contributing to growth for the tenth consecutive quarter. On the downside, mining and manufacturing were the biggest drags on GDP, collectively subtracting 0.4 ppts from growth. Mining output declined by 4.1%, with platinum group metals (PGMs) being the most significant negative contributor. Other underperformers included coal, chromium ore, gold, copper, and nickel. While iron ore, manganese ore, and diamonds posted gains, they were not enough to lift the sector into positive territory.

Manufacturing activity weakened, primarily due to lower production of petroleum and chemicals, food and beverages, and motor vehicles and transport equipment. The electricity, gas, and water sector also weighed on growth, contracting by 2.6% – its steepest decline since 3Q22 (-2.8%). The return of loadshedding after a 310-day reprieve was a key factor, while a drop in water consumption further dampened performance.

Figure 2: Industry growth rates, 1Q25

Source: Stats SA

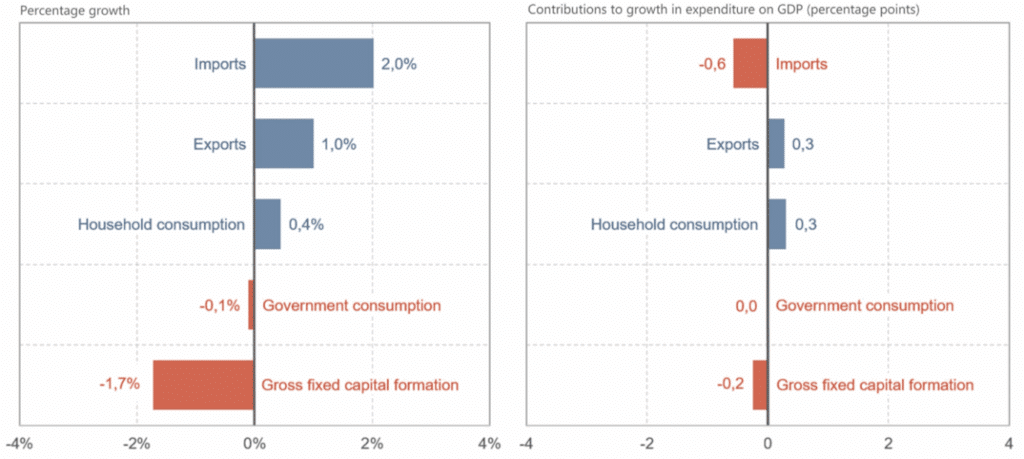

The expenditure side of the economy grew marginally by 0.1% in 1Q25 compared to the previous quarter. This modest growth was supported by exports, household consumption, and a drawdown in inventories, while imports, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), and government consumption exerted downward pressure.

Household consumption rose by just 0.4% QoQ, with signs that its earlier resilience is starting to fade. While low inflation continues to support real disposable incomes, the pause in monetary easing and the waning impact of the two-pot pension system withdrawals, which allowed retirement fund members to make partial withdrawals from their retirement fund, have reduced the financial buffer available to households. Discretionary spending has slowed, with cutbacks seen in gaming and chance-based entertainment. In contrast, spending has shifted toward essentials such as transport and food, a clear indication of growing household caution amid rising uncertainty.

GFCF, a key indicator of investment in capital assets, declined by 1.7%, led by a sharp 4.5% contraction in private sector investment. Persistently low business confidence (the index currently sits at 40, well below the neutral level of 50) has discouraged new capital expenditure. Weakness was broad-based, with notable declines in residential building activity, construction works, and investment in machinery, equipment, and transport assets.

Trade dynamics presented a mixed picture. Exports increased, likely benefitting from favourable price effects due to a weaker rand, despite being held back by logistical bottlenecks, domestic production constraints, and a slowing global economy. Meanwhile, imports rose by 2.0% QoQ, detracting from GDP growth. The rise in imports was primarily driven by increased demand for chemical products, mineral products, and machinery and electrical equipment, potentially reflecting some degree of front-loading by businesses ahead of future cost pressures surrounding the tariff uncertainty.

Figure 3: QoQ % change in expenditure components and contributions to expenditure on GDP

Source: Stats SA

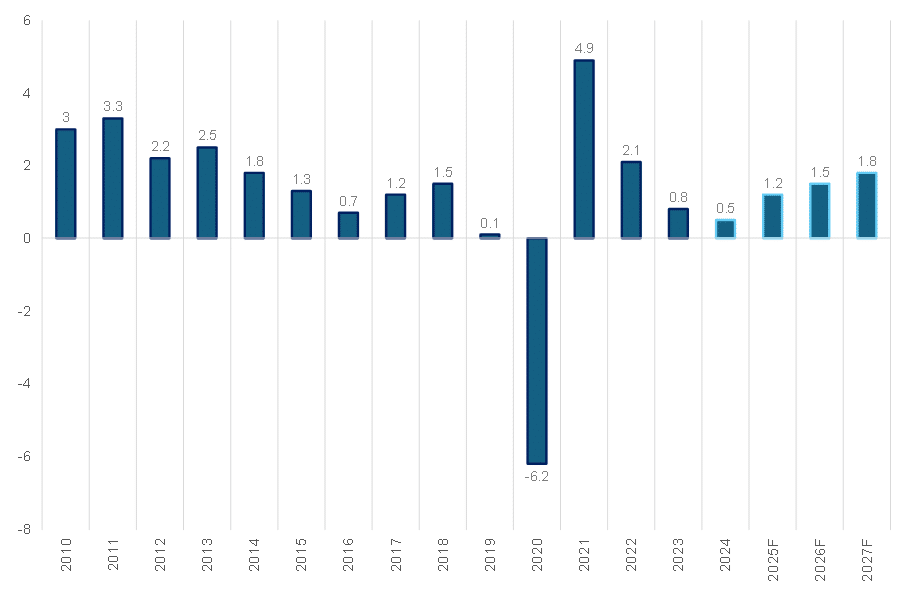

Overall, SA’s economic outlook has deteriorated, reflecting a combination of domestic political instability and mounting global pressures. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has revised its 2025 GDP growth forecast downward from 1.7% to 1.2%, citing the impact of rising global trade tensions and deepening political uncertainty at home. The IMF, on the other hand, forecasts GDP growth at only 1% for 2025. Investor confidence has been dented by ongoing discord within the GNU, raising concerns over policy direction and the potential delay of critical structural reforms.

These tensions, coupled with persistent challenges in the logistics and energy sectors, continue to weigh heavily on business sentiment and long-term investment planning. The outlook for the medium term has also weakened. The SARB has revised its forecasts for 2026 and 2027 to 1.5% and 1.8%, respectively, reflecting limited momentum in reform implementation and ongoing external risks.

Figure 4: SA GDP annual growth rate, YoY % change

Source: Stats SA, SARB, Anchor

One of the key short-term risks is the expiration of the 90-day US tariff reprieve in early July. Should no extension be granted, some SA exports to the US (the country’s second-largest trading partner) could face tariff rates of up to 30% (vs the current 10%), threatening to erode export competitiveness and suppress trade volumes. While low inflation is currently providing a buffer (supporting real disposable incomes and household spending), this is only partially offsetting the broader headwinds. Consumers are also expected to receive further support from reduced interest payments and potential withdrawals under the two-pot pension reform, which could help cushion domestic demand in the short term.

That being said, the exceptional uncertainty seen in 1Q25 – driven by delayed budget processes, tariff volatility, and questions over the GNU’s durability – has started to ease, though only marginally. In the longer term, ongoing structural reforms, if sustained, still hold the potential to lift SA’s trend growth trajectory. However, in the near term, the outlook remains constrained by weak investment, political uncertainty, and persistent external shocks, leaving the domestic economy vulnerable to downside risks.