We have just lived through close to the worst 4-year period on the JSE in the past 25 years – with a compound return of only 4.5% p.a. At a time of sustained very poor investment returns, some history lessons are needed to keep the faith.

Asset classes behave differently over time and riskier assets are more volatile, which investors have to stomach if they want an inflation-beating return over time. The frustration over the last few years has been that cash has delivered a similar return (after tax) to equities, causing investors to question the merit of equity investing.

This has also resulted in portfolios with low bond weightings underperforming inflation.

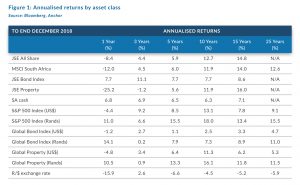

So what should investors do now? A good place to look for answers is the long-term return of asset classes. This is shown in Figure 1 below:

Over the past 3 years, equity returns have been poor (both local and global in rand terms), property returns have been negative and the rand has strengthened by 7.6% against the US dollar. The past year has been a disaster for equity assets across the board – unless you were invested offshore and measured your wealth in rand terms.

However, looking at longer term annualised returns, the answer seems obvious: equity and property is where returns are made and bonds and cash should be mixed with these to diversify, reduce volatility and lower the risk over shorter time periods. However, the last few years have been the opposite and 2018 was a particularly unpleasant ride. The natural emotional response to outcomes for the last few years is to take refuge in cash – “at least you can’t lose your money”.

However, to take this approach after a period of poor equity returns is always the wrong answer and the long-term outcome is a guaranteed return below inflation (after tax). Investors always need to take a long-term view and can be confident that long-term trends will continue, and they will diverge from these in shorter-term time periods.

Global GDP will continue to grow at 2%-4% p.a. for the next 10 years. Markets will be cyclical and volatile, but big global companies will grow their earnings at 5%-8% in US dollar terms p.a. over the next ten years and these companies will pay out dividends which will increase that return by 2%-3% p.a. Companies will get cheap and expensive but, over time, share prices will grow in line with these earnings. That 7%-11% p.a. growth in dollar terms is what has been delivered for the past 25 years and one can be fairly certain that this will be repeated in the next 25 years.

What investors will have learnt is that almost no investment professional can tell you with certainty when this will happen and what will happen in the short term – there wouldn’t be 200 asset management companies and 10,000 advisors in South Africa if any one consistently got it right. We all rely on history to a certain extent and returns over the past four years have been very poor by historical standards.

A logical response to the information provided to add value to your long-term return is to increase the proportion of asset classes which have performed poorly over a three-year period and likewise to take profits on those that have flourished. Right now that means more equities and, in SA, more property as well – although the SA 2018 property return had more to do with one basket of related companies than the market as a whole.

Another part of the when problem is that equities move sharply and often when least expected. Returns often come at times of highest anxiety (when valuations are correspondingly low) and a year’s returns can often be generated in a month or two.

One naturally wants to be invested in equities only when it feels comfortable – but that approach will see an investor deliver a much lower return over time. It’s mostly too late when it feels comfortable. Stay invested in quality companies that will grow their earnings over time, allocate capital smartly and earn a high return on the capital that they don’t return to investors.

We then need to consider our situation as South Africans, with a rand that fairly predictably depreciates at 4%-6% p.a. over the long term – that implies a rand vs US dollar exchange rate of R25/$1 by 2030. Looking at Figure 1 above, when investing in rand, a high-quality global equity portfolio is a pretty compelling proposition. JSE returns sometimes compensate for SA’s higher inflation rate (it has over 15 years), but it certainly makes sense to diversify out of just SA equities.

One also has to take SA political risk into account (although US President Donald Trump’s antics make our politics relatively more tolerable). Again the answer is to diversify out of any one specific risk.

One positive aspect of the SA investment environment is that it is easier to earn a real low-risk yield than in offshore markets. Cash beats inflation by around 2% (at 6.8%) and bonds by 4% (at c. 9%). This is justified by the higher risks, but the returns are there nonetheless. So, while equities are essential for longer-term returns in SA, cash and bonds are a comfortable parking bay.

There will always be calamity headlines, new risks emerge and subside on Bloomberg every day, but over the long term the pattern is fairly predictable.

The sermon above might be cold comfort for investors who need sustained inflation-beating returns in the short term. It is here where a financial advisor can guide you through the shorter-term anxieties and pressures, ensuring you don’t act emotionally to reduce your long-term return.