Market participants are once again concerned about the US dollar’s role as the world’s dominant reserve currency. For decades, the dollar has stood as the premier reserve currency and backbone of the global payments system. It is worth noting that concerns over the dollar’s dominance are not new. These concerns date back to the 1960s, when French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing used the term “exorbitant privilege” to criticise the advantages the US enjoyed from the dollar’s status as a reserve currency. More recently, doubts about the dollar’s supremacy intensified after the freezing of Russia’s foreign exchange (FX) reserves following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

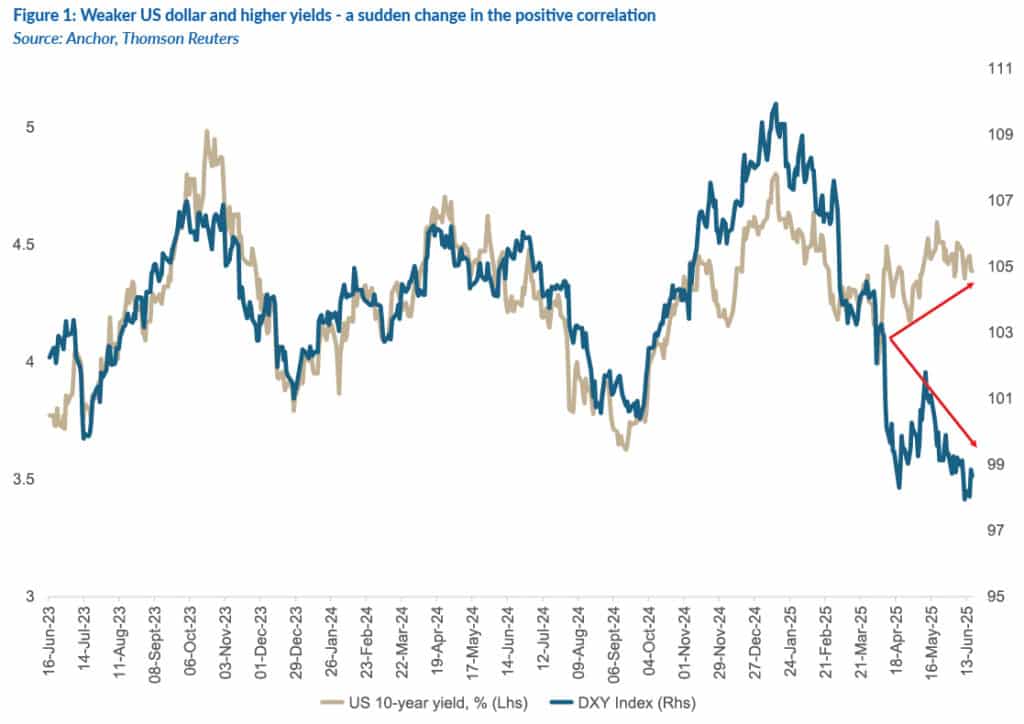

What is unsettling markets currently, however, is the simultaneous sell-off of both the US dollar and US government bonds (Figure 1). This runs counter to their traditional safe-haven roles during times of high market volatility and de-risking. Even when the US was at the centre of a crisis, as it was during the global financial crisis (GFC), investors still flocked to the safety of the US dollar and US government bonds. The sudden change in the positive correlation between bond yields and the dollar is indeed unusual. As the global economic order undergoes a structural shift with trade imbalances getting re-worked, we are bearish on the US dollar, not because it is on the verge of losing its reserve currency status, but because cyclical forces are turning negative.

The shrinking share of the US dollar in global reserves

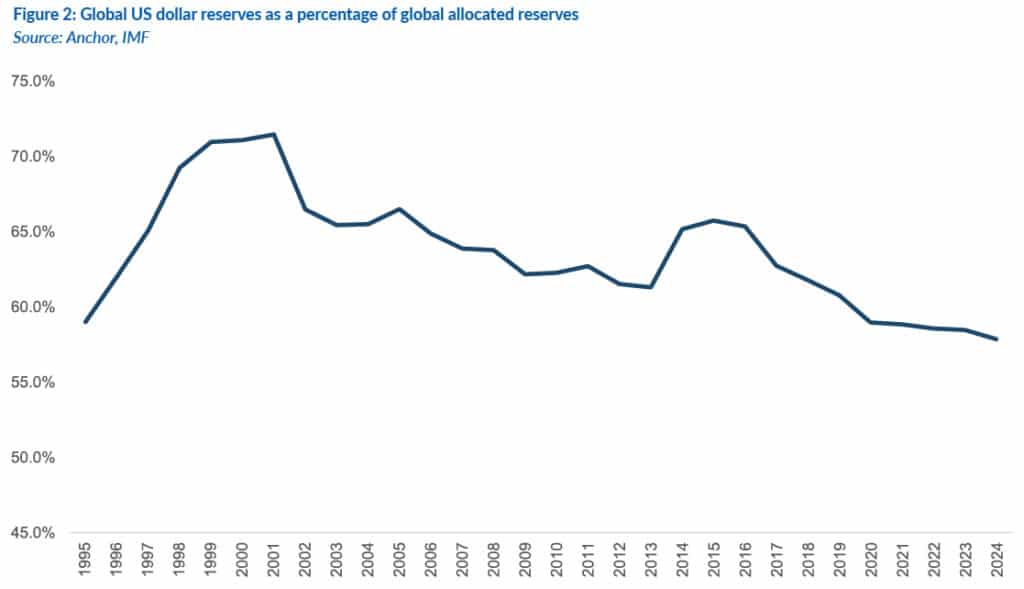

Since displacing the British pound in the 1920s, the dollar has dominated global FX reserves and become the premier reserve currency. At the turn of the millennium, it accounted for roughly 72% of total reserves. Due to geopolitical and geostrategic shifts, the dollar’s share of global FX reserves has steadily declined over the past 25 years, now sitting at around 57% — aside from a temporary rebound during the European sovereign debt crisis (Figure 2).

Does the US dollar have a viable challenger?

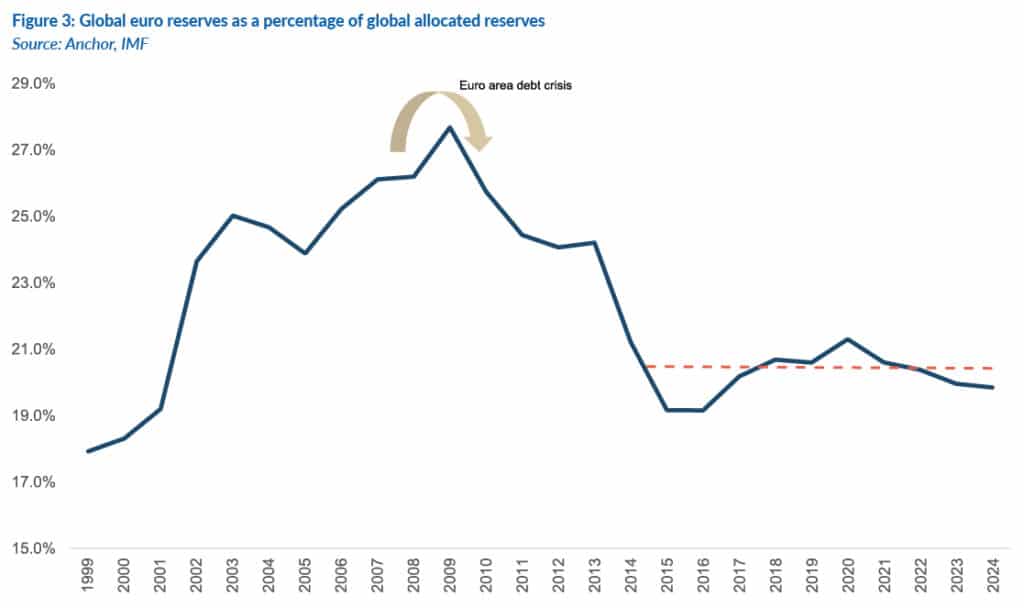

For the first decade after the euro’s launch in 1999, the euro was seen as the dollar’s most credible rival. Backed by a large economic bloc and developed financial markets, it reached a peak reserve share of 28% in 2010 (Figure 3). However, the European sovereign debt crisis, a period of financial instability in the eurozone from around 2009, exposed structural weaknesses in the EU. Since 2015, the euro’s reserve share has stabilised at around 20%, close to where it was at the start of the millennium.

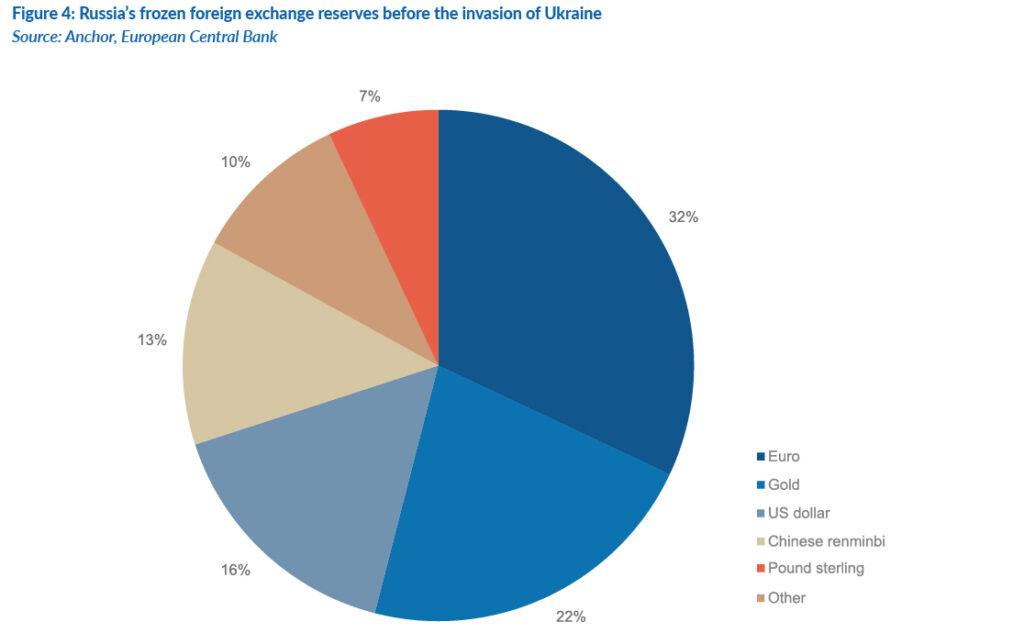

Another limiting factor for the euro was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia spent years shifting its reserves out of the dollar and into the euro (Figure 4). All of Russia’s G10 FX reserves have subsequently been frozen. Nearly 50% of Russia’s frozen reserves were in the euro compared to about 25% in the dollar.

The ease with which the US and other developed nations were able to implement asset freezes and sanctions on Russia caught the attention of some countries worried they might someday get locked out of the global payments system. This geopolitical shock underscores the vulnerability of holding major currency reserves.

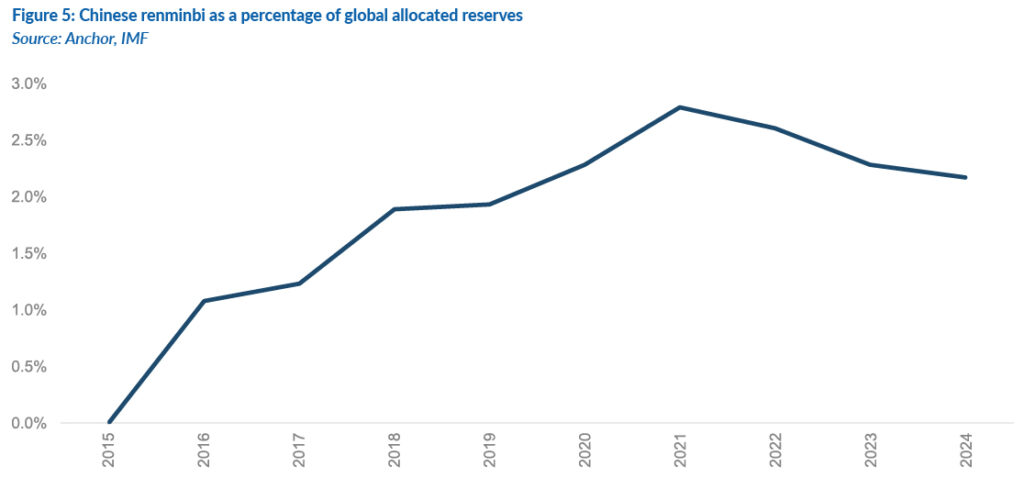

After the European sovereign debt crisis, the euro’s shine faded dramatically. At the same time, there was optimism about the Chinese renminbi. China led the global economy out of the GFC as there was still significant enthusiasm over the country’s long-term growth, fuelled by a credit binge which began in the early 2000s. The IMF started reporting Chinese renminbi reserves in 2016, and there was a moderate uptake until 2021 (Figure 5).

Since then, reserve holdings in Chinese renminbi have declined, coinciding with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is because reserve managers are worried about the geopolitical rivalry between the US and China. The potential for US sanctions has raised concerns about whether China is “investable”. Further limiting the Chinese renminbi is that it is not freely convertible for capital account transactions.

Where are reserve flows going instead?

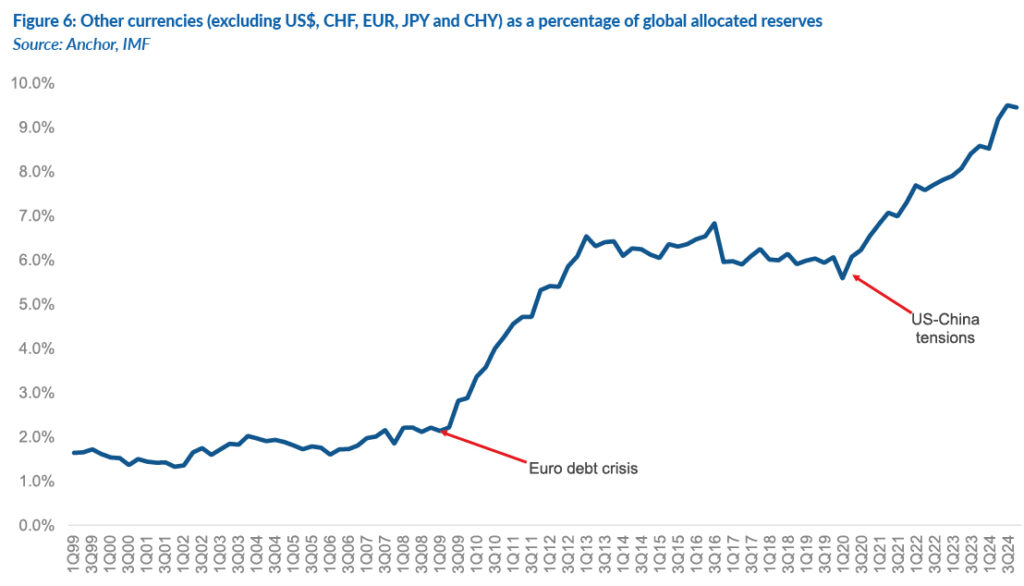

As discussed above, the decline in the dollar’s dominance has not translated into stronger demand for the euro or Chinese renminbi. Instead, central banks have diversified into so-called “non-traditional” currencies – including the Canadian dollar and Australian dollar. Allocations to these currencies have climbed from under 2% in 2000 to nearly 10% today (Figure 6). The growth has occurred in two phases, first, around the European sovereign debt crisis. The second coincided with the rising geopolitical tensions between the US and China. But given that these currencies have relatively low liquidity, it may not be possible for reserve managers to increase their allocation significantly more.

What about gold?

Aside from currencies, Central banks have also turned to gold, particularly since 2022. The freezing of Russia’s reserves highlighted the appeal of physical assets held domestically, beyond the reach of sanctions. That said, like the “non-traditional currencies”, gold’s role as a major reserve asset remains constrained by market size. We estimate that the liquid, tradeable gold stock amounts to c. US$3.5trn – far below the nearly US$13trn in total FX reserves held globally.

A move away from the US dollar – current account balances

While there is no viable alternative to the dollar from a reserves point of view, there is one other way for the rest of the world to wean itself off the US dollar. This could also explain the sudden change in correlation between US bond yields and the US dollar, as markets are forward-looking.

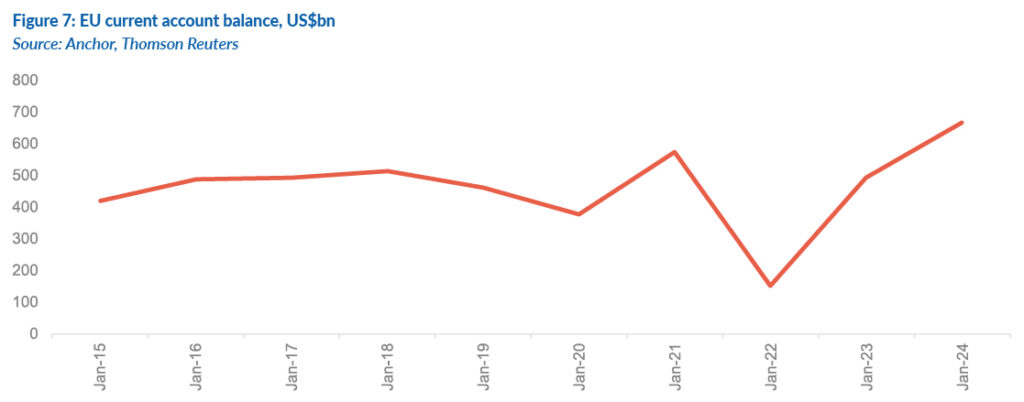

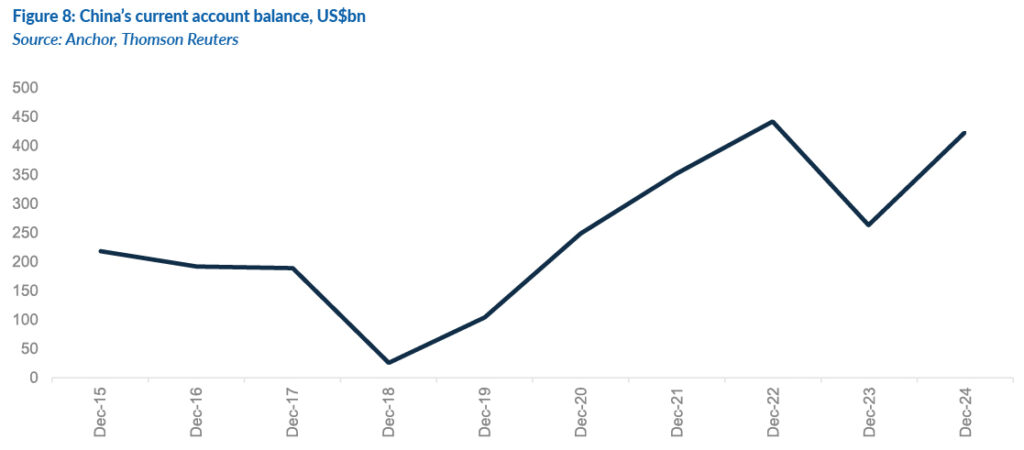

The rest of the world is currently flooded with excess savings (see Figures 7, 8, and 9). By definition, a current account can be expressed as the difference between national (both public and private) savings and investment. China, the EU and Japan are running massive current account surpluses. At current exchange rates, these three economic blocs have an aggregate current account surplus above US$1.1trn on an annualised basis. For the rest of the world to wean itself off the US dollar, it must stop generating so much excess savings.

According to macroeconomic principles, excess savings must flow to countries running current account deficits. The US currently runs a current account deficit of about US$1.2trn and offers the deepest and most liquid financial markets capable of absorbing this substantial pool of excess savings. In comparison, other deficit economies are simply too small to accommodate the vast volume of excess savings generated globally (Figure 10).

With Germany and China looking to ease fiscal policy, these are early signs that the rest of the world’s pool of excess savings may begin to shrink. If a larger share of EU and Chinese savings is redirected inward, less savings will flow abroad. For the US economy, a reduction in excess savings in the rest of the world can lead to one of two outcomes: higher bond yields or a weaker dollar. Since the Fed targets interest rates (ultimately the neutral rate) rather than the dollar, US bond yields will broadly reflect the Fed’s stance, a pro-cyclical fiscal position and a jacked-up term premium on long-term bonds. This will then leave the dollar to absorb the impact of less excess savings from abroad flowing into the US.

In summary, while there are currently no credible challengers to the US dollar’s status as the world’s premier reserve currency, the dollar remains vulnerable. If the rest of the world begins to generate fewer excess savings, there will be less savings available to fund US deficits. Our bearish outlook on the dollar is not driven by fears of an imminent loss of reserve currency status, but rather by negative cyclical factors. Lower global savings, a relative slowdown in US growth momentum compared to the rest of the world, and a narrowing of the dollar’s yield advantage are likely to weigh on the dollar’s performance.