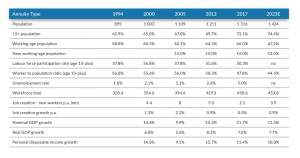

Figure 1: Key demographic and labour metrics: A bull case for India

Source: IMF, Census, UN Population database, National Sample Survey Office, Labour Bureau

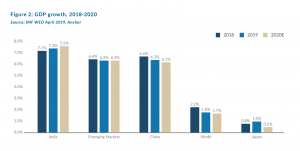

Following a lengthy elections process of deciding the next prime minister of India, Narendra Modi (leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP]) was reelected as head of state for a second term in May 2019. Modi, perceived by many as a reformist, market-friendly leader, first came into power in 2014, with the promise of structural reforms underpinning a strong focus of freeing up economic bottlenecks and the liberalisation of the Indian economy. Over the past 5 years Modi’s “new-India” has already become the world’s fastest-growing large economy. However, we believe the dividends of the improved investment climate in India is only in its infancy, with many more years of above-trend economic growth ahead. At Anchor, we are constructive on the Indian investment case and we have exposure to the Indian growth story across various mandates in our business.

As a country of c. 1.3bn people, India is by far the most populous democracy in the world. The sheer size of the country, with varying cultures and religions, has made the process of governing India highly complex with various forms of economic policy dictating the country’s direction post-colonial rule (India gained independence in 1947). Socialism dominated in the mid-1960s to early 1980s, which was then followed by a period of deregulation and ultimately, from the early 1990s, the economy embarked on various forms of liberalisation, the most transformative of which was the first term of the Modi government, which delivered GDP per capita growth of c. 7% p.a.

Figure 2: GDP growth, 2018-2020

Source: IMF WEO April 2019, Anchor

Few countries have the demographic attributes for economic success as strong as India, with increased optimism around the country’s untapped growth potential premised on the back of the so-called “demographic dividend”. According to data from the World Bank, over the coming decade India’s workforce is set to surpass that of China and, for the first time in a generation, the Chinese will be dethroned as the largest labour pool in the world. It is estimated that over the next 5 years, 13mn new job seekers will enter India’s working-age population p.a. and, with a labour force participation rate of c. 54%, the number of new job seekers will increase by approximately 7mn people – an increase of c. 1.5% p.a. In context, in absolute terms, the addition to India’s labour force over the next 5 years will be greater than the rest of the Asia Pacific region, the US and the EU combined!

This supplementation to the global workforce differentiates the Indian investment case relative to its EM peers. However, the growing working-age population is only a boost to growth if the number of people entering the workforce is growing faster than the overall population (as dependency ratios decline), the persons actually find work and the long-term savings rate continuously ticks higher (leading to increased investment rates). The biggest challenge for Indian policy makers is creating the required investment climate that would encourage the necessary investment in ultimately putting the millions of new job seekers to work productively. Creating productive jobs is a far more difficult task today than it was a few decades ago when China went through its greatest economic transformation. An abundance of cheap labour was the foundation of China’s manufacturing boom and, all things being equal, India is in quite a similar position to that of China 20 years ago (in terms of its access to labour and low levels of debt to GDP). However, as the global shift towards automation is inherently less labour-intensive, India will have to be very innovative in its pursuit of productive job creation.

The composition of the labour market and how productive each new job is towards economic growth is symptomatic of many developing countries. C. 45% of the current c. 450mn jobs in India are in agriculture, with a very low contribution towards economic growth as agriculture has the lowest productivity rate of any form of employment.

India’s economic growth has long been dominated by domestic consumption and, for sceptics, the key concern is India’s recent history of job creation, with only 2mn jobs created p.a. over the past 5 years. With 22mn people living below the poverty line and over half the working population employed in jobs with very low productivity, and a further 14mn new job seekers entering the labour market every year, India’s structural reforms will need to be targeted at stimulating the manufacturing and export economy to avoid the potential demographic tailwind from becoming a crippling burden on the state. However, stimulating the manufacturing sector relies heavily on access to capital and promoting investment. With a large percentage of lending still being controlled by state-owned banks, the market has in recent years been dominated by poor credit controls and high levels of non-performing loans (NPLs). This has resulted in reduced access to funds desperately needed to boost the manufacturing sector. A recapitalisation of state-owned banks is a step in the right direction, however, privatisation of those institutions is ultimately what’s needed in order to ensure capital is deployed in the most efficient manner.

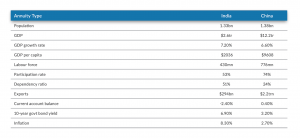

While the world continues to shift away from labour-intensive manufacturing hubs, India’s population demographics dictate that policy makers ultimately have no choice but for India to become a global leader in low-cost manufacturing if it wants to avoid high levels of unemployment and achieve economic growth at the targeted 8% p.a. This comes at a time where the Chinese labour force is shrinking, the structure of that economy is shifting from one dominated by investment to one dominated by consumption. Add to that the post WWII low in the relationship between China and its biggest trading partner (the US), and India’s stars could potentially be fortuitously aligning.

If India’s competitive advantage over the next ten years relies on an inexpensive and young labour force, then recent developments between the US and China could ultimately turn out to favour India. However, India will need to tread carefully in its dealings with a volatile US President, Donald Trump. As it stands, India currently has a modest $24bn trade deficit with the US (China by comparison has a $420bn deficit), which it will look to grow over time. However, Trump’s recent decision to strip India of its preferential access to the US market (the day after Modi’s inauguration) is a definite step in the wrong direction. India’s loss of privilege, which was instituted by the US in order to aid the economies of less developed countries, will impact c. $6bn worth of goods previously imported to the US duty-free. While the quantum is not material in the context of India’s c. $83bn worth of exports to the US – the move is more indicative of the Trump regime’s hardening stance towards, and obsession with, trade deficits. Given India’s need to build out its export capacity, it appears to us as though India simply cannot afford strained relations with the US.

Figure 3: India vs China economic indicators comparison

Source: Bloomberg, IMF, Census, UN Population Labour Bureau

In Modi, India has a leader who seems unafraid to make bold decisions. BJP’s 2014 election manifesto made sweeping statements about tackling corruption and simplifying the tax system. This was followed up with the controversial process of demonetising high-denomination bank notes, resulting in an estimated 1%–1.5% knock to the country’s GDP in 2018. At the time, these measures seemed like an extremely risky way of tackling corruption, however, one year later the number of taxpayers have risen by 25%. Another controversial move was to broaden the tax net through the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax (GST), which replaced several state and federal taxes, with the aim of taxing consumption and simplifying the collection process.

This time around the decisions may need to be even bolder. Sweeping labour (removing friction in the labour market) and financial market reforms are just a start. A multi-year, $1.4trn, fiscal stimulus package was announced in the lead-up to the election, and with government debt to GDP at 70%, the capacity to inject capital into the economy is available. However, it would need to be allocated very efficiently in order to sustainably boost economic growth.

Some of the more immediate reforms will likely include increasing flexibility in the labour market.

In previous published research on India, we highlighted the deteriorating demographics of many global economies. Shrinking workforces and high levels of debt to GDP are, under conventional economic theory, not inputs to sustainable economic growth (the so-called “Japanisation” of the world). India is positioned as an outlier from a demographics point of view; however, Indian policy makers will need to be bold in the pursuit of lifting millions of its people out of poverty and fulfilling its economic potential.

At Anchor our primary exposure is to India’s financial sector, via our investment in ICICI Bank with our expectation that ICICI (and privately-owned Indian banks in general) will be a pivotal capital provider for the expected uptick in investment spending and at the front line of much-needed economic reform.