As governments worldwide grapple with the intricate challenges of escalating geopolitical uncertainty, mounting nationalism, burgeoning debt burdens, and the pressing need to finance green and digital transitions, a silent yet pervasive force continues to siphon public resources – the shadow economy. This global phenomenon, often camouflaged in plain sight, encompasses economic activities that operate beyond the purview of formal institutions, evading registration, regulation, and taxation. It permeates all income brackets and geographical regions, casting its shadow on both advanced and developing economies. Its implications are profound, from undermining fiscal structures and distorting competition to eroding state capacity and, in many cases, delaying structural development.

The shadow economy refers to unrecorded or underreported economic activity—whether legal or illegal—that escapes regulation, taxation, or official statistics. It is distinct from, but closely related to, informal employment, tax evasion, and fraud. The key characteristic is non-compliance with administrative procedures, including registration, taxation, and reporting obligations. Examples range from cash-in-hand labour and unregistered small businesses to off-the-books income and illicit transactions. While often small-scale or driven by necessity in low-income settings, the shadow economy can also include significant underreporting by registered firms seeking to avoid tax, regulation or scrutiny.

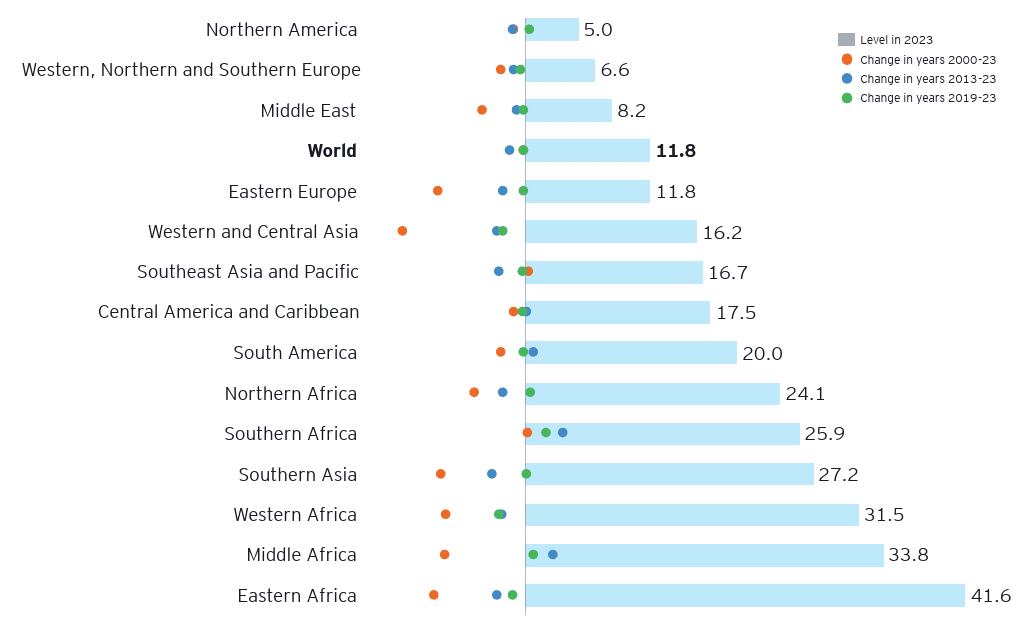

Importantly, the shadow economy is not a fringe phenomenon. It is a systemic issue that affects macroeconomic performance, governance quality, and long-term investment prospects. EY’s March 2025 report entitled Shadow Economy Exposed: Estimates for the World and Policy Paths brings much-needed analytical rigour to this global challenge. Spanning 131 countries and applying an advanced econometric approach, the report presents a nuanced picture of the size, scope, drivers and fiscal implications of the shadow economy. The global shadow economy, according to EY’s estimates, represented approximately 11.8% of global GDP in 2023. When calculated as the average across all countries (without adjusting for GDP size), the figure rises to 19.3%, reflecting the outsized role shadow activity plays in many smaller and developing economies. There is considerable geographic variation: the smallest shadow economies are found in North America, Western and Northern Europe, and parts of the Middle East, typically ranging from 5% to 8% of GDP. The largest are concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where shadow economic activity can reach 24% to over 40% of GDP.

Figure 1: Shadow economy by regions, level in 2023 and changes over time (percentage of GDP)

Source: EY analysis

Despite the daunting figures, there is reason for optimism. Over the period from 2000 to 2023, a significant majority of countries (119 out of 131) managed to shrink their shadow economies, with 67 countries witnessing a reduction of more than five percentage points of GDP. This progress, however, was not uniform, with setbacks occurring in regions facing severe economic shocks and institutional weaknesses, such as Southeast Asia and Southern Africa.

What drives the shadow economy? A multi-faceted picture

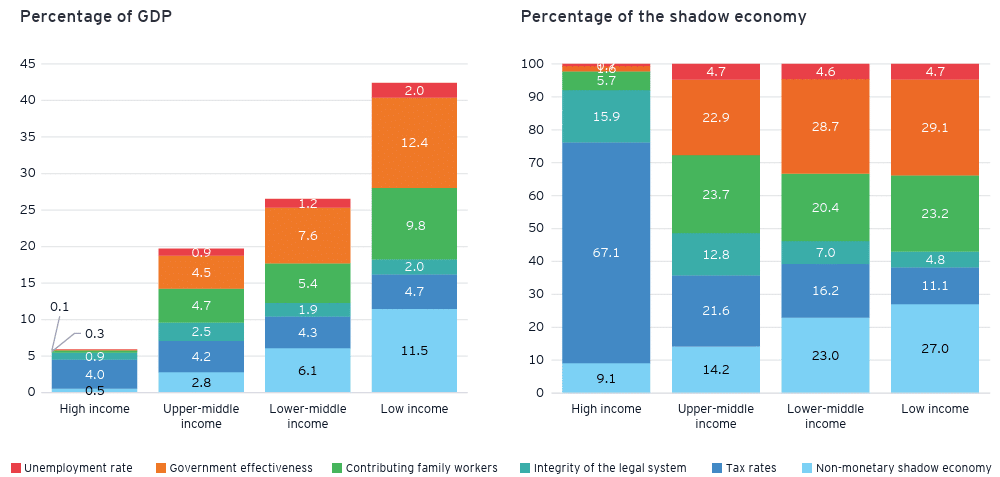

Understanding the drivers behind the shadow economy is essential to grasping why it persists—and why it proves so difficult to dismantle. These underlying causes are far from uniform; they vary significantly across countries depending on levels of economic development, institutional strength, labour market structures, and tax regimes. In lower-income economies, informality is often a function of necessity—an outcome of weak governance, limited access to finance, and inadequate formal employment opportunities. In contrast, in higher-income countries, it is more often a matter of strategic evasion, driven by complex tax systems, high compliance costs, and behavioural incentives. This diversity of causes makes the shadow economy a deeply embedded and resilient feature of many economies, necessitating a nuanced understanding to address it effectively.

1. In low-income and developing economies: Weak institutions and necessity

In low-income economies, the primary drivers are weak governance, limited access to formal employment, and a high share of contributing family workers. According to EY’s analysis:

- Poor government effectiveness accounts for 29.1% of shadow activity in low-income countries.

- The prevalence of family-based or subsistence-level labour adds another 23.2%, suggesting that informality is often linked to broader underdevelopment and a lack of formal opportunities.

In these settings, the shadow economy acts as a survival mechanism rather than a strategic choice. However, while it may provide short-term income, it undermines broader development goals by reducing tax collection, limiting access to finance, and perpetuating low productivity.

2. In high-income economies: Tax avoidance and regulatory arbitrage

In contrast, the drivers in advanced economies are more institutional and behavioural:

- High tax rates—particularly on income and business profits—are responsible for 67.1% of the shadow economy in high-income countries.

- Legal system inefficiencies, while less significant, still contribute to strategic underreporting and regulatory evasion.

Here, participation in the shadow economy is often a matter of choice, facilitated by opportunities to misreport or hide income. The challenges are less about access and more about incentives, trust in institutions, and compliance dynamics.

3. Informal employment and the shadow economy: A strong correlation

Unsurprisingly, the EY report finds a strong positive correlation between informal employment and the size of the shadow economy. In many low- and middle-income countries, informal employment makes up a much higher share of total employment than the shadow economy does of GDP. This reflects the fact that unregistered labour is often lower-value and excluded from national accounts. Conversely, in high-income countries, the problem tends to revolve around revenue underreporting by formally registered businesses.

Figure 2: Shadow economy by income groups: Contributions of different drivers in 2023

Source: EY analysis

The economic trade-offs of the shadow economy

The shadow economy imposes a significant fiscal burden by eroding government revenues, particularly from VAT, corporate income tax, and personal income tax. By operating outside formal systems, informal businesses and workers undermine the tax base needed to fund infrastructure, health, education, and social protection. In some countries, tax losses from cash-based shadow activity alone can exceed 5% of GDP. These shortfalls reduce public investment capacity, especially in states with already limited fiscal space.

Beyond lost revenue, informality distorts market competition. Formal firms carry the cost of compliance, while shadow operators do not, discouraging innovation, scaling, and capital investment. This imbalance entrenches inefficiency and undermines productivity. Equally concerning is the gradual erosion of trust in public institutions. When non-compliance appears widespread or enforcement is weak, taxpayers lose confidence in the system, weakening overall tax morale and making governance more difficult. At a macro level, the impact is far-reaching as constrained revenue limits governments’ ability to pursue countercyclical fiscal policy, increases reliance on debt, raises borrowing costs, and can elevate sovereign risk, particularly in economies with fragile fundamentals.

Yet, the shadow economy also provides certain short-term economic functions. In many low-income or fragile contexts, it serves as a critical fallback, offering income and employment where the formal economy cannot, such as in the South African (SA) economy. It absorbs surplus labour during crises and can act as the first step for small-scale entrepreneurship in underserved areas. Informal earnings, though unrecorded, often feed into local consumption and demand, providing a degree of economic resilience. However, these benefits are frequently temporary and come at the expense of long-term development. Informality tends to trap workers in low-productivity, precarious jobs with limited upward mobility. Informal firms struggle to grow, access capital, or join formal value chains—ultimately limiting national productivity and deepening inequality. While the shadow economy may offer functional short-term relief, its long-term effects represent a persistent drag on fiscal health, institutional capacity, and sustainable economic growth. Addressing it requires thoughtful, inclusive strategies that support formalisation without penalising those for whom informality is a matter of necessity.

From local informality to global impact

The shadow economy is a complex, entrenched challenge that varies across regions and income groups but carries universal consequences. It limits the effectiveness of public policy, weakens fiscal foundations, distorts competition, and impairs the investment climate. For governments, reducing informality should be a fiscal and developmental priority – not just to raise revenues, but to build stronger institutions, fairer economies, and more resilient societies. For investors, the size and structure of the shadow economy should form part of the broader risk assessment toolkit.

Economies with declining informality often exhibit improving governance, rising productivity, and more stable fiscal outlooks—traits that support sustainable, long-term investment returns. Overall, the shadow economy presents both a challenge and an opportunity. It reflects gaps in development, governance, and market access, but also reveals untapped potential. Harnessing that potential through thoughtful, data-driven formalisation strategies is essential—not only for improving fiscal health and investment conditions, but for building more inclusive, resilient economies in the decades ahead.