European equities often trade at a discount to their US peers. Major EU Banks, for example, trade at up to a 50% valuation discount to comparable US Banks (See the article, “French Banks and Macroeconomic Convergence” in our 2nd Quarter 2018 Strategy Report). Whether or not one is enticed to buy this differential depends, to a significant degree, upon one’s assessment of certain key longer-term, structural, features of the EU. Further, given that the EU is the second-largest contributor to global GDP, one’s assessment of the sustainability of the global expansion also depends on one’s assessment of Europe’s outlook. This note focuses on the structural side of the European investment case. It briefly addresses five key questions in this regard. This analysis is not a substitute for cyclical analysis, but rather a kind of background which facilitates the interpretation of shorter-term, cyclical, data.

In short, we ask: (1) How problematic is Europe’s “lack of fiscal integration”? In our view, a lack of fiscal integration is not necessarily a problem; indeed it may be an appropriate counterweight to monetary and other forms of centralisation. (2) Is the refugee crisis also an economic crisis? We show that migration has slowed dramatically in the past 18 months, thereby reducing the stress placed on EU infrastructure. To the degree that EU immigrants are successfully integrated, they may improve the region’s poor demographic outlook, thus bringing an unanticipated boon. (3) Is Emmanuel Macron credible? We argue that he is, especially in light of his existing and prospective successes at reform. (4) How vulnerable is Europe to a trade war? Europe would be highly vulnerable to a generalised global shift towards protectionism, and indeed protectionism seems to be a deeply rooted phenomenon. Yet we think trade tensions will be, for the most part, contained to the China-US relationship. (5) Is the euro a double-edged sword? While ECB QE was highly effective because of its effects on the euro, the impending end of QE could see growth under pressure as the tide reverses. Further, the euro removes certain economic stabilisers associated with a national currency, thereby making certain economic adjustments more painful and protracted. Thus, the first four questions suggest a basically positive long-term outlook for Europe. These are, to a degree, offset by concerns attached to the euro. On balance, this analysis suggests that the investment case for Europe is structurally sound.

- How problematic is the “lack of fiscal integration”?

The EU is often considered to be structurally flawed for having monetary but not fiscal integration. That is, the ECB sets eurozone monetary policy, but fiscal policy varies by country. The IMF has been a major proponent of this view, i.e. the view that a lack of fiscal integration is a problem, and it has filtered into financial markets’ research as a standard point against the European investment case. Here we revisit this critique, and argue that it may be incorrect, or at least overstated.

A recent IMF article notes that the EU “also requires a fiscal union to take the edge off country-specific macroeconomic shocks. Established currency unions, such as those in large countries with multiple regional governments, include automatic risk-sharing mechanisms, the most efficient way to insure against business cycle risks.” It goes on to argue: “An added benefit of introducing some fiscal risk sharing could be more fiscal discipline. This may seem counterintuitive given that, as with any other insurance mechanism, adding fiscal risk sharing is bound to introduce moral hazard, or the temptation to make riskier decisions in the knowledge that an insurance mechanism is in place. For example, governments may put less effort into meeting fiscal targets.” On the other hand, however, “more risk sharing could make the euro area’s ‘no bailout’ rule more credible and thereby make financial markets pay more attention to fiscal misdeeds.”1

We think there are three key features of this argument. First, the lack of fiscal integration may mean that the less fiscally sound EU nations could experience greater GDP volatility. Second, this comes with the “moral hazard” of encouraging fiscal imprudence. Third, fiscal integration could result in fiscal discipline. In our view, this argument is not particularly compelling. It seems more likely that the risks of moral hazard outweigh the possible benefits of greater stability and an apparently low probability that this will introduce “fiscal discipline”. Indeed, one might ask whether the EU’s lack of fiscal centralisation is rather a healthy kind of decentralisation that counterbalances monetary centralisation.

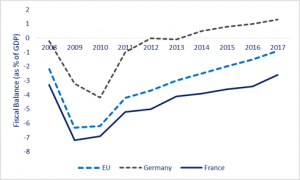

But what of fiscal discipline, the third key point noted above? In our view, Europe has clearly demonstrated fiscal prudence in recent years. The EU’s budget deficit is now under 1%, with all the region’s economies, except for Spain, operating within the EU’s budget constraints. Although France was until very recently in breach of deficit limits, this has been rectified, as of 2017. Similarly, Spain’s 2017 budget marginally exceeded the 3% limit, at 3.1%, but looks set to be comfortably within the 3% mark during 2018. Thus the region is, in aggregate and by individual member, well within its prudential fiscal limits.

The rise of populism in Europe is, in part, a reaction against centralisation. It expresses the view that the EU is infringing on the sovereignty of individual nation states. Thus, in addition to the “moral hazard” of fiscal centralisation, there seems to be a risk of further aggravating populist impulses. This issue is itself interesting and complex. Here, one could note how modern capitalism has been infringing on sovereignty for decades: nation states, for example, are held to account by bond markets that “discipline” those given to fiscal profligacy; similarly, the US Federal Reserve cannot really hike rates unless the bond market has already given it the “go ahead” through sufficiently high implied probabilities of such a hike.

These considerations reinforce the view that political actors, such as the new Italian Government, are not really autonomous agents. Rather, they make choices within constraints, many of which are imposed by financial markets. The market does not always block bad choices in advance, but it does seem to punish them (as seen, for example, in the case of Greece). The new Italian government is now most likely to challenge the status quo, and it will be important to watch how it negotiates the conflict between the market-imposed constraints, and its own political ambitions. It is due to present its 2019 budget by mid-October, which should provide important insights on this score.

This backdrop, we think, should inform one’s interpretation of the paroxysms of fiscal and political ‘crisis’ in Europe. The key question is whether they are harbingers of ultimate disaster, or whether they are more like “growing pains” (i.e. it took America a long time to become the United States). That the European crises, to date, have been large enough to precipitate change, but small enough to leave the system intact, suggests that they may ultimately have a strengthening effect on the EU and its institutions. The cliché, “what does not kill me makes me stronger” (Nietzsche), may be applicable here. But, by “stronger” we do not mean more centralised power, but rather the resilience of the system, itself understood as balancing competing demands for centralisation and decentralisation. In summary, we do not think a lack of fiscal integration is necessarily a problem; indeed it may be an appropriate counterweight to monetary and other forms of centralisation.

-

Is the refugee crisis also an economic crisis?

The European refugee crisis raises many complex issues associated with human rights, justice, and economic sustainability. In this section we abstract from these difficult issues, focusing only on their economic dimension. We first consider one key risk, and then an unexpected boon that may follow from the crisis.

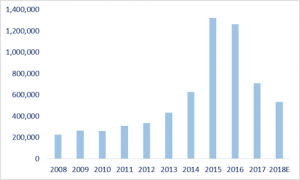

Had the arrival of asylum seekers continued at the rates seen in 2015-16, Europe may have been placed in a stressed situation, as the existing economic structures may not have been able to absorb the migrant population. Events like Brexit, for example, which come with negative economic consequences, are connected to fears and a consequent political backlash stoked by the refugee crisis. EU asylum applications have however declined dramatically since their 2015-16 peak. Applications in 2017 were 44% lower than in 2016, and in 2018-to-date, applications are down another 25% (see Figure 2: European Asylum Applications below). Consequently, we think the associated risks, noted here, have most likely fallen as well.

But the refugees may also have an economically beneficial impact on Europe. The region is typically regarded as structurally unattractive due to its demographic outlook: the average age of the population is expected to rise, and consequently the workforce, as a percentage of the population, is expected to decline. This is negative for the medium and long-term growth outlook, as well as the prospects for fiscal sustainability. If, however, Europe’s refugees are successfully integrated into society, they could tip the region’s demographic outlook into far more favourable territory.

The IMF has noted this prospect in both its 2016 and 2017 assessments of Germany, stating: “The projected decline in the labour force due to aging after 2020 calls for measures to boost labour supply in the medium term. Additional policies to integrate the current wave of refugees into the labor market […] would be important in this regard. These reforms would not only counter the projected growth decline in the medium term but also stimulate private consumption and investment in the short term.”2

In summary, we think the refugee crisis is not also an economic crisis. Its associated risks seem to have waned dramatically, but the economically beneficial consequences are still likely to materialise, particularly in relation to the EU’s demographic outlook.

-

Is Emmanuel Macron credible?

Macron is the current president of France, the second-largest economy in the EU. He was elected on a reform mandate, and is looking to slim the nation’s bloated state, and make the region economically competitive. His ambitions also have the potential to fill a leadership vacuum in the EU; a Merkel-Macron partnership is far more compelling than a German dictatorship. But many predecessors have failed in similar ambitions to reform France. Thus, one must ask: is Macron really credible? To answer this question, we briefly note some features of France’s current difficulties, a few of Macron’s successes, and some as yet unresolved complexities.

France has been an economic laggard for the better part of the last decade. While Germany, the largest economy in the region, currently runs a fiscal surplus, and also a significant trade surplus, France has not only a trade deficit, but a fiscal deficit that until very recently was in breach of EU rules. France also has a history of strong unions, and vicious strikes that tend to follow any attempt to put the welfare state on diet. How is this context reacting to Macron’s attempts to change it?

Macron has already achieved some liberalisation of the labour code, and cuts in taxes. In 2017, Parliament approved a progressive reduction in the corporate tax rate from 33% to 25% over the 2017-2025 period. One of Macron’s election promises was to bring the fiscal balance under control, thus removing France from the EU’s “excessive deficit procedure”. France had been in breach of the EU’s limit of fiscal deficits, to 3% of GDP, since 2007. But the 2017 budget balance came in

at -2.6%, and consequently the EU recently (May 2018) concluded that France’s excessive deficit is now corrected. This is a very important milestone for the country, and symbolically significant for Macron.

A major point of resistance to Macron’s reforms has been the protracted strikes by national rail workers. These are, again, both quantitatively and symbolically significant. On this point, The Economist notes: “Because of their ability to cause chaos, and the popular affection that [railway workers] enjoy in a country where railways are part of the collective imagination, railway strikes are usually an efficient way to force a capitulation.”3 Yet the magazine argues that the government looks likely to succeed. It supports this contention by noting that public support is now behind the government (64% in favour), and employee participation in the strike has fallen dramatically (e.g. “The share of train drivers on strike has fallen from 77% to just over half”). A win in this contentious domain, which now looks very likely, bodes well for further efforts at reform.

Lastly, one could note the important formative influence that philosopher Paul Ricoeur has had on Macron’s thought. The president formerly studied under Ricoeur, who was known for his ability, both practically and theoretically, to mediate apparently irreconcilable opposites. Macron’s intentions to mediate similar polarisations in the political sphere appear, therefore, to be grounded in solid intellectual acumen. One is consequently less likely to judge his mediatory ambitions as the naïveté of a relatively young politician. In summary, therefore, we think Macron has good prospects for success, both domestically and in Europe.

-

How vulnerable is Europe to a trade war?

Europe’s economic prospects are highly dependent on exports. German exports, for example, are 40% of GDP, while the EU runs a current account surplus of 3.5% of GDP. Thus, should the global environment shift towards protectionism, Europe’s growth prospects would be meaningfully affected. The usual response to threats of protectionism has been to downplay them: Trump is, so this view goes, merely grandstanding before the mid-terms. But there are reasons to see protectionism as more deeply rooted.

Protectionism is part of broader global phenomenon, which might be styled as a backlash against liberalism. Here, ““liberalism” comes with a degree of complexity, because we have had economic liberalism (an ideal of the political right or centre-right) combined with cultural liberalism (typically an emphasis of the left). Thus, events like European “populism”, Brexit, Trump’s presidency and his wall, trade protectionism and other manifestations of de-globalisation, even social developments like the “Jordan Peterson phenomenon”; these are all expressions of a backlash, however complex and multivalent, against what was the liberal consensus. As part of this, it may be that a growing proportion of DM societies is willing to accept a lower GDP growth-trajectory as the price for more equitable income distribution. This shift has been buttressed by a sense that the GFC proved that capitalism is flawed; and that income-inequality associated with modern capitalism is ethically unacceptable. Further, although China may be de facto capitalist, it is nevertheless a communist state associated with a continuing economic miracle. Thus, the drift towards protectionism seems to have quite deep roots in societal shifts, and may prove to be enduring. At the same time, there are strong incentives to keep protectionism contained and relatively modest.

Assuming, therefore, that protectionism is here to stay, what are its likely effects on Europe? Trump has introduced tariffs on EU goods, but it seems likely that China will remain the focus of his protectionism measures. Two reasons support this contention: (1) Tariff differentials between the US and China are relatively extreme, i.e. a higher degree of Chinese tariff protection has been tolerated, until recently. This is not equally apparent in the case of Europe. (2) Europe does not present a threat to US power, but China’s growing economic might is potentially threatening. Thus, a reasonable base-case, now, is for trade tensions between the US and China to escalate, but not come close to causing a recession. They will probably only modestly dampen global growth (an effect of under 0.5% on GDP growth), and fan inflation. That is, it still appears unlikely that this bilateral tension will spill-over into a broader shift to protectionism that incorporates other major economies.

From the perspective of financial markets, this protectionist development is rather more complex that it appears at first blush. Indeed, to dub it a “war” may be a mischaracterisation. For, to the extent that pure untrammelled capitalism produces a tiny wealthy elite (the “one percent”), and a disenfranchised underclass, while hollowing out the middle class, it may become a self-destructive phenomenon. Note, for example, the very high propensity to consume amongst the middle-class, and very low propensity amongst the wealthy. Thus, excessive wealth concentration is actually bad for consumption spending, therefore also for GDP and asset prices. The political right has tended to downplay this side of our current system, while the left has tended to overstate it. There may, therefore, be scope for a modest degree of protectionism that is a net-benefit to the current system.

-

Is the euro a double-edged sword?

The euro has been a great benefit to Europe in a number of ways. Amongst these, European QE was highly effective because it also weakened the euro, which in turn fanned demand for Europe’s exports. But the euro also brings certain disadvantages, both in terms of economic stability, and the likely effects of normalising monetary policy.

Negative effects on economic stability are caused because a shared currency removes an important economic “pressure release valve”. When a nation has its own currency, certain domestic rigidities and crises can be counteracted by a currency devaluation. Excessive wage hikes, for example, can be counteracted by the currency. When the currency cannot adjust to these domestic factors, which is the case for a regional currency like the euro, it may force a country into protracted economic difficulties as the imbalance is driven through other channels. Thus, for example, a country may simply have to stomach nominal wage cuts in lieu of a currency adjustment. This tends to be a far more painful and protracted process. One is not likely to get riots when the currency adjusts by 10%, as one is quite likely to see for a similar downward adjustment to wages.

The euro may also pose problems when the ECB starts to unwind QE. This has the potential to cause very significant euro strength, and thus risks derailing the growth recovery. It seems, consequently, that the ECB’s QE unwind will be a very gradual and protracted affair.

Conclusion

The first four questions, considered here, suggest a basically positive long-term outlook for Europe. But these are offset, to a degree, by the concerns attached to the euro: both in relation to the unwind of QE, and the lack of national currencies which mitigate certain risks. Although this note has focused on five key questions, there are many other issues which inform our stance but which we have not focused on here. Amongst these, we have some concern that: the EU’s consensual decision-making structure tends to create headwinds for structural change; EU Banks are over-regulated; and in some domains, such as Italy, legal infrastructure can be archaic and stifling. Our conclusion that Europe is ‘structurally sound’ should not, therefore, be taken to mean it is uniformly positive. Every jurisdiction has its problems, and Europe is no exception. Our analysis suggests that on balance, and in spite of our concerns, the investment case for Europe is structurally sound.

There are at least two practical implications to draw from this: (1) Europe should remain a positive contributor to global growth. This provides support for a basically pro-cyclical asset allocation, which favours global equities. (2) The main structural negative relates to the euro’s sensitivity to monetary policy normalisation, and the consequent impact of European GDP. This means that, in addition to being some years behind the US in monetary policy normalisation, the EU will probably also move more gradually once normalisation does begin. This does somewhat temper the investment case for EU Banks. Nevertheless, their valuation multiples are so depressed – especially in light of this note’s basically positive structural assessment of Europe – that one could still hold EU Banks at a modestly overweight position. This is especially so, if one has the luxury of a two-year investment horizon, by which time ECB hikes should have begun. Consider, for example, that a rerating of large French Banks to a 1x P/Book multiple, along with their attractive dividend yields, could generate an IRR of just under 50%. The hurdle-rate for a neutral allocation, given our assessment of EU risks, is closer to 10% (our 12-month expected return on global equity is 7% in US dollar terms; EU Banks demand a risk premium relative to this benchmark). Thus, in our view, the weakness of French Banks’ share prices, seen this year, presents an opportunity.

Figure 1: European Fiscal Budgets are demonstrating prudence

Source: Trading Economics; Bloomberg

Figure 2: European Asylum Applications – significantly down from the 2015 peak

Source: Eurostat