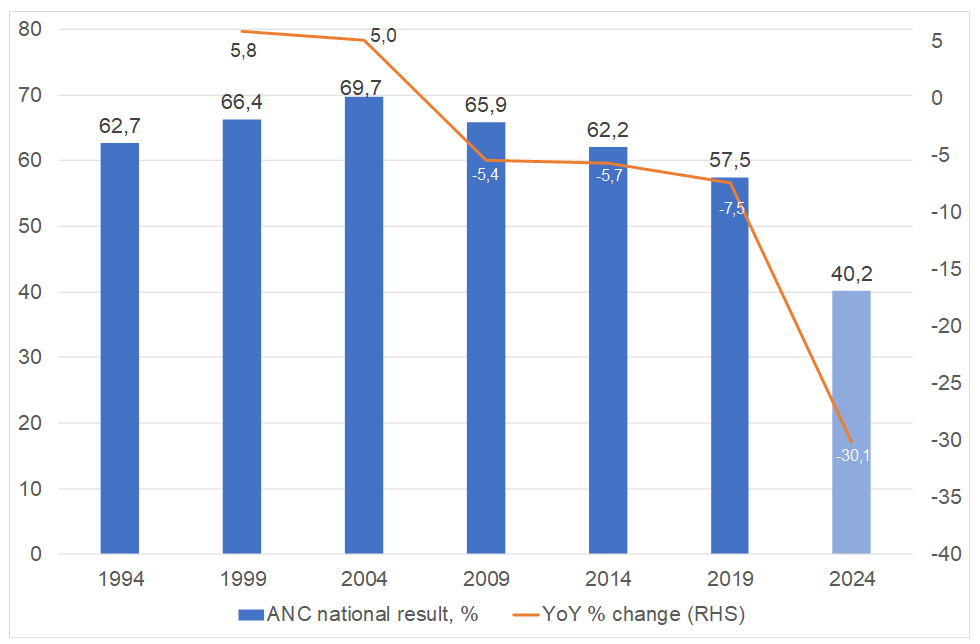

In this note, we delve into the seismic impact of the ANC losing its Parliamentary majority for the first time since the dawn of democracy in 1994. We refrain from delving into the potential performance of any other political party, given the sheer size of the ANC and its stranglehold on South Africa’s (SA) political landscape over the past 30 years. It is crucial to note that this report does not endorse the ANC or any other political party. In what follows, we review the past three decades of ANC dominance, highlight the results provided by the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), give an overview of the various ANC presidents’ tenures since 1994, discuss the state of the ruling party since Cyril Ramaphosa’s ascendancy to the presidency and briefly look at the way forward.

Without running the risk of using hyperbole, it is safe to say that the 2024 National and Provincial Elections (NPEs) have ushered in a new era in South African politics – the era of coalitions. The election on 29 May 2024 was a watershed moment for the country as it was the first time in democratic history that the ANC lost its majority in government – going from 57.6% in 2019 to 40.2% in 2024. The emergence of ex-president Jacob Zuma’s new M.K. party cut severely into the ANC’s traditional voter base in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and eroded support for the former ruling party in Gauteng and Mpumalanga. As a result, there is a need to form complex, multi-faceted national coalitions to govern SA for the next five years.

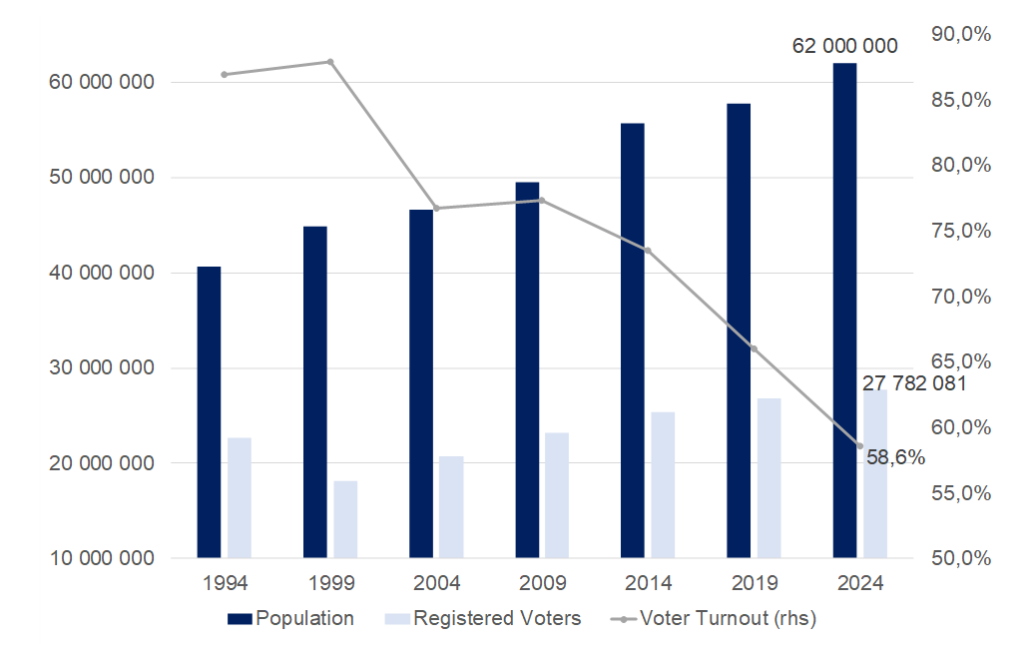

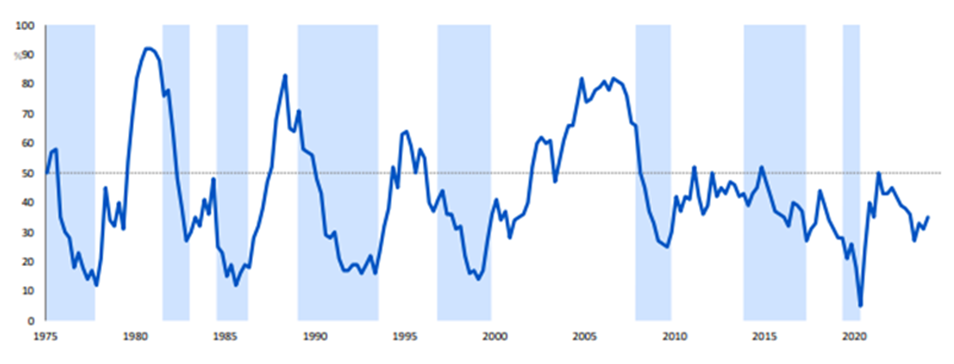

The significant drop in voter participation (at 58.64% of the total 27.8mn registered voters vs 65.99% in 2019 – see Figure 1) reflects the general disillusion and greater disengagement of the South African populace with the country’s electoral process and greater political leadership. The ANC has attained 159 seats in the National Assembly – down 31% from its previous 230 seats.

Figure 1: Voter turnout, 1994-2024

Source: IEC, Stats SA, Anchor

How did the SA economy fare under various ANC presidents?

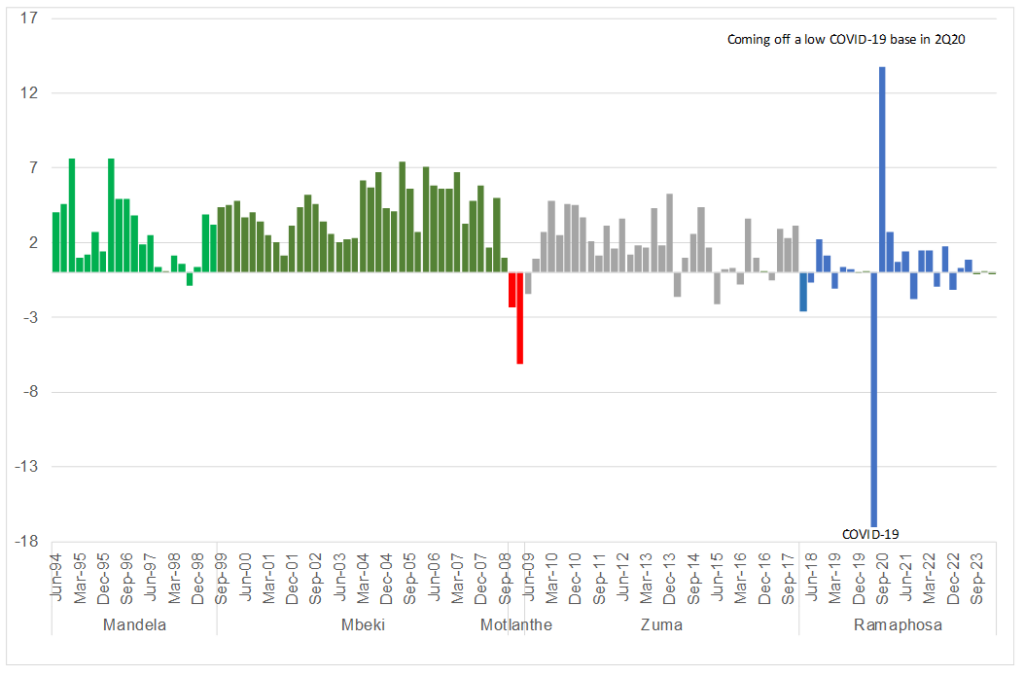

During the Nelson Mandela (1994-1999) and Thabo Mbeki (1999-2008) years, SA’s economy thrived as the government adopted a mix of socio-economic, fiscal consolidation and more investor and pro-business friendly economic policies whereby the country moved from fiscal bankruptcy (under Apartheid, pre-1994) to a budget surplus. However, Zuma’s disastrous tenure dragged SA back to pre-1994, while COVID-19 and indecision/inaction from President Cyril Ramaphosa to address the structural issues in the local economy saw his tenure to date disappoint. The average GDP growth rate was 4.2% for Mbeki’s presidency, and SA recorded 37 consecutive quarters of positive economic growth (notably with Trevor Manual as his finance minister). After Mbeki resigned (effectively recalled in September 2008) and Kgalema Motlanthe took over as interim president, SA posted its first recession (4Q08 and 1Q09 recorded negative growth) since 1994. During the Zuma presidency (May 2009-February 2018), average GDP growth slowed to c. 1.8%. Some extraneous factors contributed to the slowdown in SA’s growth under Zuma, including the petering out of the commodities super-cycle. The commodities boom, which started in 2000 (during Mbeki’s tenure), was disrupted by the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 and started fading around 2012/2013. However, maladministration, policy uncertainty, corruption on an unprecedented scale (the Guptas, Bosasa, etc.), a revolving door of key ministerial positions (especially the finance portfolio), and uncertain economic and fiscal policy drove investment (both foreign and domestic) away.

Figure 2: GDP (QoQ annualised growth) under each of the democratic presidents, 2Q94 to 1Q24

Source: Bloomberg, Anchor

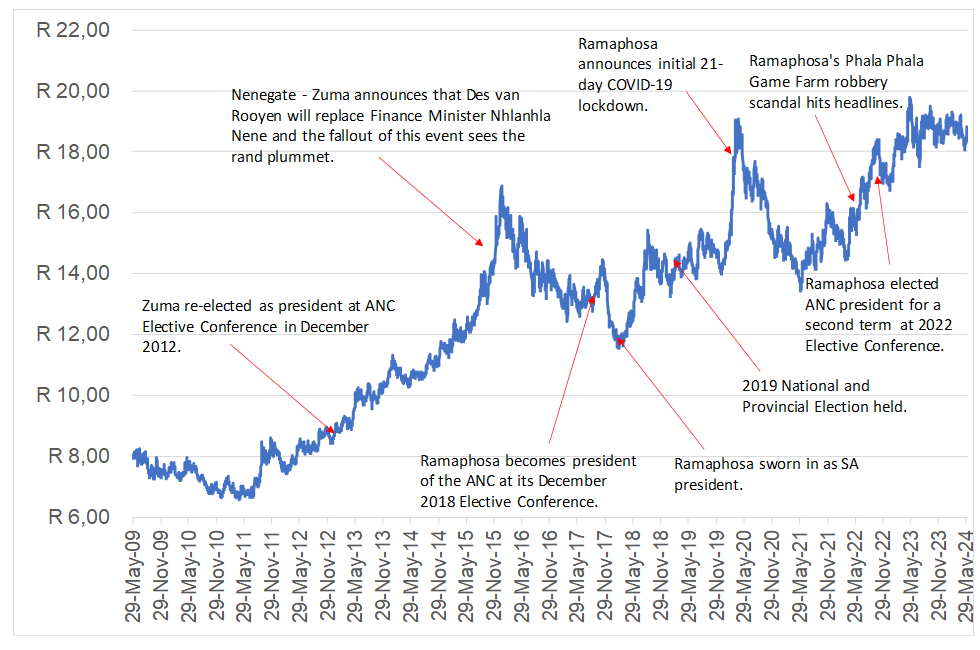

When Zuma took office (9 May 2009), the rand vs US dollar exchange rate stood at c. R8.27/US$1. However, the average exchange rate for 2017 (the last year of Zuma’s rule – he left office on 14 February 2018) was at R13.31/US$1 – a c. 61% depreciation throughout his presidency vs a c. 30% decline in the rand during Mbeki’s presidency. After Ramaphosa was elected president of the ANC in 2017, the rand went from R14.47/US$1 to R11.55/US$1. However, during Ramaphosa’s presidency (from February 2018 to 31 May 2024), the rand has plummeted by 62.7% against the greenback. When Mbeki took over from Mandela, the official unemployment rate stood at c. 22% – it is currently at 32.9% (1Q24), according to Stats SA’s latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS).

Figure 3: Rand vs US dollar exchange rate during Zuma and Ramaphosa tenures

Source: Bloomberg, Anchor

The fragility of the SA economy (with opposing forces in the ANC making the right economic outcome challenging to achieve) is underscored by the fact that Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s) downgraded SA’s sovereign credit rating to junk (with a negative outlook) in March 2020, joining Fitch and S&P, which already had SA at sub-investment grade. Moody’s was the only major rating agency with SA at ‘investment grade’ – one notch above junk (with a stable outlook). However, Moody’s downgrade resulted in SA falling out of the FTSE World Government Bond Index (WGBI).

Structural issues facing the country

Gross debt (a combined c. R5.2trn or 73.9% of GDP in 2023/2024) and corruption at state-owned enterprises (SOEs), such as Eskom, SAA, Transnet, and the SABC (to name but a few) spiralled out of control during Zuma’s tenure – now effectively referred to as the state capture period. Unfortunately, little has been done to abate this trend under Ramaphosa. Eskom’s debt alone is now c. R442bn (c. 15% of all sovereign debt), and the situation became so dire that the entity had to borrow funds to pay interest on this debt to keep the lights on. For most of his presidency, Ramaphosa has been walking a tightrope – at ease with having the law take its course while being careful to “appease” the so-called Zuma faction of the ANC. Ramaphosa, it seems, has been trying to prevent a split in the party, similar to what happened when ex-president Mbeki resigned and the Congress of the People (COPE) was formed. By all accounts, he wanted to negotiate a path forward with a divided organisation – a strategy that resulted in the ANC’s undoing in the 2024 election.

Ramaphosa’s December 2017 Elective Conference victory as ANC president was clinched by a very slim margin (less than 200 votes out of the c. 5,000 cast by delegates), indicating a questionable command of the party’s reins at that stage. However, his election as ANC president for a second term in December 2022 saw a more commanding victory over his challenger, disgraced former health minister Zweli Mkhize, with Ramaphosa garnering 2,436 votes ahead of Mkhize’s 1,897. The composition of the 86-member National Executive Committee (NEC) was split virtually 50/50 in terms of Ramaphosa supporters and those in the Zuma camp in 2017. However, following the 2022 ANC Elective Conference, at least 65% of the 80 NEC members (excluding the top six) appeared on a list of preferred candidates drafted by the president’s camp. Ramaphosa’s backers secured four of the top-six positions.

Regardless, election outcomes are only one piece of SA’s increasingly complex economic puzzle. SA has numerous long-term structural economic issues (some of which have already been mentioned), which Ramaphosa has not addressed, at least not to the degree South Africans would have hoped. Eskom loadshedding accelerated under his watch, and the country has only had an uninterrupted electricity supply for around five weeks now, the longest without loadshedding since 2022.

The healthcare system faces challenges, along with a concerningly high unemployment rate (32.1% as of 4Q23, with youth unemployment at a tragically high 59.4%). It is confronting a massive disease burden, while most school education quality is substandard. The legacy of corruption is not only undermining the legitimacy of the state but, tragically, impacting service delivery to voters, especially the most vulnerable.

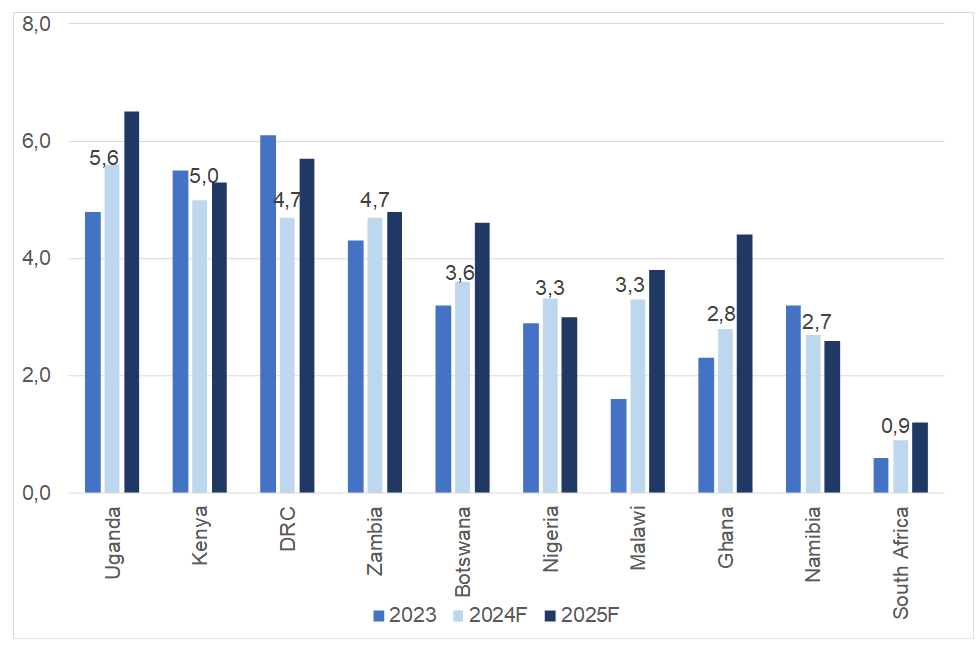

In April 2024, the IMF said that SA has a GDP of US$373bn (R7trn-plus), making it the biggest economy in Africa (the IMF projects that SA will retain this position until 2027). According to the IMF, Nigeria’s GDP is estimated at US$253bn, behind Algeria (US$267bn) and Egypt (US$348bn). Still, despite being Africa’s biggest economy, it cannot seem to rid itself of the deep-rooted structural inequalities holding back growth and development due to the rampant corruption that has plagued the country over the past 15 years or so. SA’s economic performance has been one of the weakest in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with the IMF lowering its 2024 forecast for real GDP growth to 0.9% (from 1.0% in January) in April. Moreover, the average SA consumer is becoming poorer – with the latest IMF data indicating that SA’s GDP per capita is now below the average for emerging economies – and at about the same level as in 2005. According to IMF data, SA’s GDP per capita dropped from US$6,680 in 2022 to US$6,190 in 2023 – far below the record-high of US$8,800 recorded in 2012. Additionally, the 2023 domestic GDP per capita is below the US$6,450 average for emerging markets (EMs). Notably, this is the same level of GDP per capita as in 2005. Simply put, SA’s expanding population growth, the weakness of the rand and the minimal economic growth means that the country’s population has been getting poorer in real terms. Moreover, in the domestic economy, material job creation has only occurred when GDP growth approaches 3% p.a. Thus, the economy is simply not growing at an adequate rate to sustainably boost long-term employment prospects for South Africans.

Figure 4: IMF GDP growth data (select African countries)

Source: IMF, Anchor

Note above is sorted according to each country’s 2024 forecast GDP growth.

The IMF’s recent downgrade of SA’s growth to 0.9% means, in context, that our growth rate is far below the EM average (4.2%), the global average (3.1%) and is lower than that of SSA (+3.8%). According to the latest June data from RMB/BER, the Business Confidence Index (BCI) stood at 35% in 2Q24 – roughly just over one-third of the survey’s respondents were satisfied with prevailing business conditions. Simply put, meaningful job creation and sustainable economic growth can only come to fruition with a more favourable investment environment- not policy misalignment, governance uncertainty and prevalent corruption. Collaboration between government, business, and labour is required to place the country on a renewed growth path – away from conflict and individual vested interests around growth that will, in turn, create jobs and a thriving economy where everyone benefits.

Figure 5: RMB/BER Business Confidence Index (BCI)

Source: BER (note that the shaded areas represent economic downswings)

What has Ramaphosa achieved thus far?

While Ramaphosa has made some commendable decisions and changes, many commentators have highlighted that it will take years for him to address the problems facing SA due to the state-capture era administration he inherited from Zuma. Moreover, he has had to carefully navigate his political survival due to the continued presence of Zuma allies within the ANC, who naturally do not want their patronage network/s dismantled. Despite the challenges (and disappointments) of the Ramaphosa presidency, we view him as a far wilier politician than most expect (he did, after all, negotiate at CODESA, spent years in the National Union of Mineworkers [NUM], was elected ANC secretary-general and headed the ANC team that negotiated SA’s transition to democracy). By allowing the law to take its course, he is not taking it upon himself to act against “comrades” and risking the ire of some in the ANC, but rather doing it ‘by the book’. Unfortunately, as the saying goes, the wheels of justice turn slowly (but grind exceedingly fine). Every week, a punch-drunk SA public has been bombarded with more revelations about corruption and no arrests. However, unlike under Zuma’s tenure, there seem to be consequences, albeit at a frustratingly glacial pace. Ramaphosa’s attempts at a clean-up have, over the years, seen several commissions being set up by the president and several initiatives launched by Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan, including new boards at SOEs, lifestyle audits and difficult questions being asked around the financial (mis)management of SOEs.

In terms of just some of his achievements in his c. six years in office, while critics have accused him of being slow to act and keeping corrupt Zuma-era cabinet members, Ramaphosa has, in addition to the above, strengthened SA’s law-enforcement institutions that were decimated under Zuma and given attention to issues at SOEs. Unfortunately, Eskom power cuts have worsened and were part of daily life in SA until about a month ago. Some of the more cynical citizens have seen the improvement in generation capacity as an election ploy on the part of the ANC. Ramaphosa also signed the controversial National Health Insurance (NHI bill) in May, which many have seen as an electioneering ploy which has spectacularly failed in getting the ANC votes.

Where are we currently?

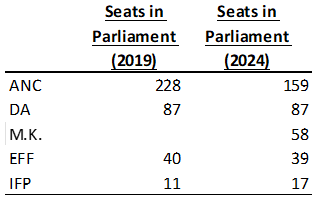

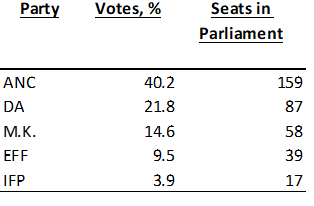

The ANC performed dismally in the 2024 NPE, falling to a 40.2% vote, as Zuma’s M.K. party devoured a large chunk of ANC voter support. The three-month-old party became the third biggest in the country, with a staggering 14.6% of the vote. The seats in Parliament that the top five political parties received in the 2019 NPE are shown in Figure 6 below and compared with the seats for the 2024 NPE. The ANC received 58% of the vote in 2019 vs 62% in 2014. According to the IEC, this year’s voter roll contained 27.8mn registered voters, higher than in 2019, but nevertheless indicating that 13mn-plus citizens of voting age have chosen not to register for this election.

Figure 6: 2019 vs 2024 seats in Parliament for the top-five parties

Source: IEC, Anchor

Figure 7: 2024 NPE results – votes and seats in Parliament for the top-five parties

Source: IEC, Anchor

Figure 8: ANC 2024 NPE results and YoY % change, 1994-2024

Source: IEC, Anchor

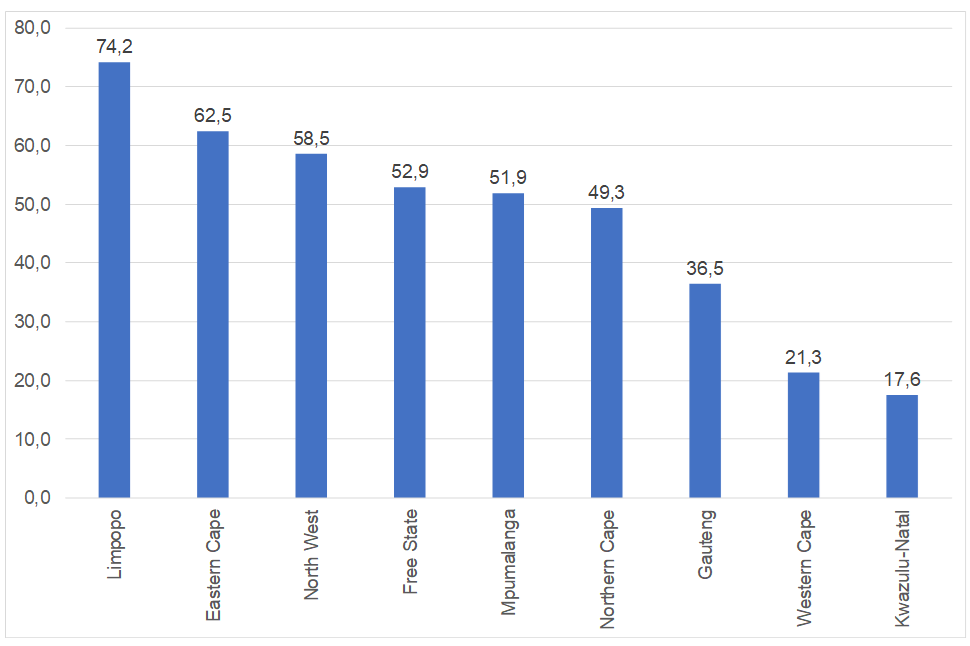

Figure 9: 2024 NPE results – ANC vote by province

Source: IEC, Anchor

Figure 10: Seats in Parliament by political party following the 2024 NPE results

Source: Daily Maverick, Anchor

Looking ahead- where do we go from here?

Currently, the ANC appears set to form a GNU, where all parties above a certain threshold are invited to join the ANC in government. This agreement would allow Ramaphosa and his allies to accommodate opposing groups within the ANC and effectively ‘unite’ against the M.K. party. Whilst the DA would likely be reticent to work alongside the EFF in such a set-up, the party will be placed in an uncomfortable position due to its well-communicated promise to ‘do everything in its power’ to prevent the ‘Doomsday’ ANC/EFF coalition. Whilst this would likely be one of the more market-friendly outcomes, a GNU agreement would not be without uncertainty or immune to fractious in-fighting. Regardless, at this point, no one is sure what the outcome will be – not even the ANC. However, the clock is ticking, and the first sitting of the National Assembly, where members are sworn in and the speaker is elected, must occur within 14 days after election results are declared. The Chief Justice of the Republic (Raymond Zondo) will determine and gazette the date for this sitting. During this first Parliamentary sitting or soon after that, the National Assembly will elect the president, who is responsible for appointing cabinet members and forming the government. The entire process is usually completed within a couple of weeks to ensure a smooth transition of power.

Despite the current uncertainty and very present, real challenges around the election outcome, it is important to note that the 2024 elections were credible and sufficiently ‘free and fair’- something not to take for granted at this point in SA’s democratic transition.

Where to from here for investors?

Diversification is key to reducing risk when investing. The thinking is that if an investor mixes a variety of investments in their portfolio, on average, it will yield higher long-term returns and lower the risk of any single holding. In this regard, we need to consider our specific situation as South Africans, with a rand that somewhat predictably depreciates at a rate of 4%-6% p.a. over the long term – implying a rand vs US dollar exchange rate of c. R25/US$1 by 2030. A high-quality global equity portfolio is a compelling proposition when investing in the rand. JSE returns sometimes compensate for SA’s higher inflation rate (over 15 years) but diversifying out of SA equities certainly makes sense. One also has to consider SA’s political risk (which includes crucial global elections that are on the horizon, such as the highly contested US Presidential Election in November), and again, the answer is to diversify out of any one specific risk.

At Anchor, our clients come first. Our dedicated Anchor team of investment professionals are experts in devising investment strategies and generating financial wealth for our clients by offering a broad range of local and global solutions and structures to build your financial portfolio. These investment solutions also include asset management, access to hedge funds, personal share portfolios, unit trusts, and pension fund products. In addition, our skillset provides our clients with access to various local and global investment solutions. Please contact Anchor for more information.