“There is no such thing as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. A hurried mind is an addled mind; it cannot see clearly or hear precisely; it sees what it wants to see, or hears what it is afraid to hear, and misses much. A knight makes time his ally. There is a moment for action, and with a clear mind that moment is obvious.” – Ethan Hawke, Rules for a Knight.

This advice is timeless and was first penned by Sir Thomas Lemuel Hawke of Cornwall in 1483 during his last days before he died in battle. He wished to pass along to his four children a compass for their life’s journey and wrote them a letter which was later adapted and reconstructed by Ethan Hawke of Dead Poets Society fame and a four-time Academy Award nominee (twice for writing and twice for acting). The resultant fable is a series of ruminations on solitude, humility, forgiveness, honesty, courage, grace, pride, and patience. He draws on the ancient teachings of Eastern and Western philosophy, and on the great spiritual and political writings of our time. It is a profoundly simple read.

Warren Buffet, who needs no introduction, has said that “investing is simple but not easy”, however, putting into practice the simplicity of plain math and plain language is another story. For many, this is because of the psychological pitfall of not having the capacity to accept or tolerate delay, problems, or suffering, without becoming annoyed or anxious. This is the definition of patience.

Regular readers of Anchor’s The Navigator will know that one of my passions is the field of behavioural finance. Financial behaviour tends to be more emotional than rational and our financial behaviour, as with the rest of our actions, is a deep-rooted expression of our internal psychology. As human beings, there are numerous behavioural biases that impede our ability to reason if we do not understand these inclinations and make a conscious effort to work around them.

If you google “patience in investing”, more than 13,200 results come up and the mathematical and real-world examples of the power of compounding are easily searchable. In The Navigator – Anchor’s Strategy and Asset Allocation 2Q19, Matthew Stroucken wrote an article entitled The most difficult thing in investing- the power of compounding, which succinctly summarises the power of compounding and notes that the most difficult thing in investing, is staying invested due to our behavioural biases. In this note, I would like to provide some practical insight and practices for understanding our inclinations to be impatient and how we can make a conscious effort to work around them as investing is not about timing the markets, but time in the markets.

Increasingly so, people want instant gratification and one of the most underused investing skills has nothing to do with the ability to value equities or bonds, analysing financial statements or economies but rather in the diligent process of practising patience. Jason Zweig, author of the book Your Money and Your Brain: How the New Science of Neuroeconomics Can Help Make You Rich has the view that the three qualities an investor needs above all others are independence, scepticism and emotional self-control.

Emotional self-control is the ability to manage disruptive emotions and impulses and to maintain effectiveness under stressful or even hostile conditions.

So, how do we develop the capacity to accept or tolerate delay, problems or suffering without becoming annoyed or anxious? How do we gain self-control over our emotions? How do we stay calm in situations where we lack control? How do we practise patience?

In this case, practise really does make perfect.

Before you berate yourself for not being patient across all areas of your life, I would like to remind you that you can blame your brain here. Human beings were designed to react to threats, either real or perceived. Stressful situations trigger a physiological response in people – a “fight-or-flight” mode. The body cannot differentiate between psychological triggers, such as turbulent equity markets, and actual physical danger. Unfortunately for impatient investors, when emotions take over, the result is often poor decision-making that could decrease the risk of meeting future financial objectives. Practising patience means learning to overcome these natural instincts. Sacrificing in the short term for the longer-term benefit. As with all emotions, we do not want to suppress them but rather learn how to control these emotions.

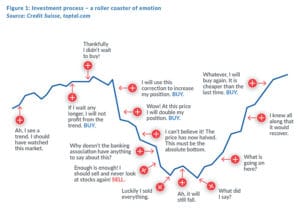

Echoing the opening quotation, cognitive science tells us that the more upset you are, the less you can focus satisfactorily on what is important, take it in deeply, or respond nimbly. Being “hijacked” by your emotions, sabotages your ability to make good decisions or to react skillfully. Market volatility is an easy trigger to overwhelm and, because our bodies and our brains cannot differentiate between real or perceived threats, they perceive a threat to our financial well-being (which is not a physical threat) and this triggers the fight-or-flight response. Your emotions take control, and your brain is shouting: “Do something!”.

Sometimes, the best action to take is taking no action. Do something by doing nothing.

Another psychological phenomenon that comes into play here is negativity bias: There is this seemingly neverending stream of negative news and we are hard-wired on an evolutionary level to focus more on the bad news than (admittedly, the harder-to-find) good news.

Both Benjamin Graham, who also needs no introduction, and Warren Buffet consider patience – or lack thereof – as a defining trait of success in investing.

Patience + investing = a natural partnership.

The most benefit lies in investing for the long term and it is no coincidence that the benefits of patience too, are long term. You must be able to endure some short-term hardship for that future reward. Impatient investors let anxiety and emotion rule their decision-making. Their tendency towards “doing something” can lead to detrimental investing behaviour: checking account balances too often, focusing on short-term volatility, selling or buying at the wrong time or abandoning a long-term strategic investment plan. Often these behaviours damage investors’ long-term returns.

In addition to taking no action, what are some of the other practical tools we can practise to cultivate patience (and returns) for the long term?

- Fail to plan and plan to fail: One of our primary roles as your wealth managers at Anchor is to help you plan. We are here to map out your long-term investment journey and then to navigate stormy seas with you.

- The only constant is change: I have been working in the investment industry for twelve years and I cannot think of a single year in which we have not experienced volatility. I am surrounded by far more experienced professionals, and I am confident they will attest to the same, as they often do. Volatile markets are normal. Accept them as a given as this will help you to mentally prepare and equip you to take control of your emotional thoughts and reactions.

- Time in the markets is more important than timing the markets: Often you will benefit by being invested in the market more than by trying to find the perfect time to invest. Being invested is the only way you benefit from the wonder that is the power of compounding.

- Determine the difference between fear and fundamentals: Not to be viewed as a contradiction to everything I have said, sometimes you have to do something. Is the volatility due to fear or fundamentals? If the former, do nothing. If the latter, yes, it would be best to restructure if the long-term fundamentals of a share, economy or your personal financial situation have changed. We have a team of highly skilled, both from a technical and practical perspective, analysts who will do this analysis work for you and you are always more than welcome to contact your manager at Anchor to talk through your long-term strategic investment strategy. Sometimes, tactical changes may be necessary. As Ethan said, there is a moment for action and, with a clear mind, that moment is obvious. Although, I would reiterate here that sometimes doing nothing is the active choice.

“In the end, how your investments behave is much less important than how you behave.” — Benjamin Graham

Personally, I find this comforting. I can control my behaviours but not those of others.