Peter manages the Anchor Global Stable Fund and co-manages the Anchor Managed Fund and has been with Anchor since November 2013. Prior to joining Anchor, Peter spent 16 years working for various global investment banks in New York and London, most recently as head of portfolio management for Credit Suisse’s systematic hedge funds.

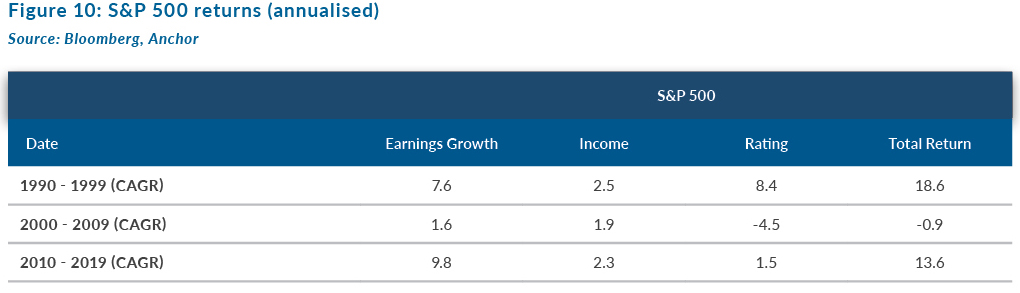

The term “Lost Decade” was originally coined to refer to Japan’s economic downturn that lasted throughout the 1990s, when a Japanese stock market and real estate bubble burst resulting in a debt crisis and a decade of deflation and sub-par economic growth. The term was then recycled to describe the US stock market after the first decade of the 21st century saw the S&P 500 Index deliver a negative total return of 9.1% (-24.1% excluding dividends).

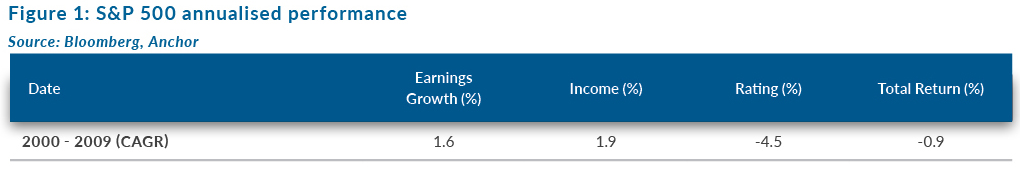

The trouble for the S&P 500 in its lost decade was mostly just random timing, with the decade bookended by two major earnings collapses, the “tech bubble” to start the decade (earnings down 21% in 2001) and the global financial crisis (GFC) to end the decade (earnings down 36% in 2008).

Although that decade still saw the S&P 500 Index grow earnings by an aggregate 1.6% p.a., the valuations leading into the decade were so elevated from the “tech bubble”, that a de-rating in valuation was inevitable and ultimately the source of the negative returns for the decade.

After a dismal period for the local economy and domestically focussed stocks, it now seems perhaps appropriate that SA takes ownership of that moniker for the most recent decade.

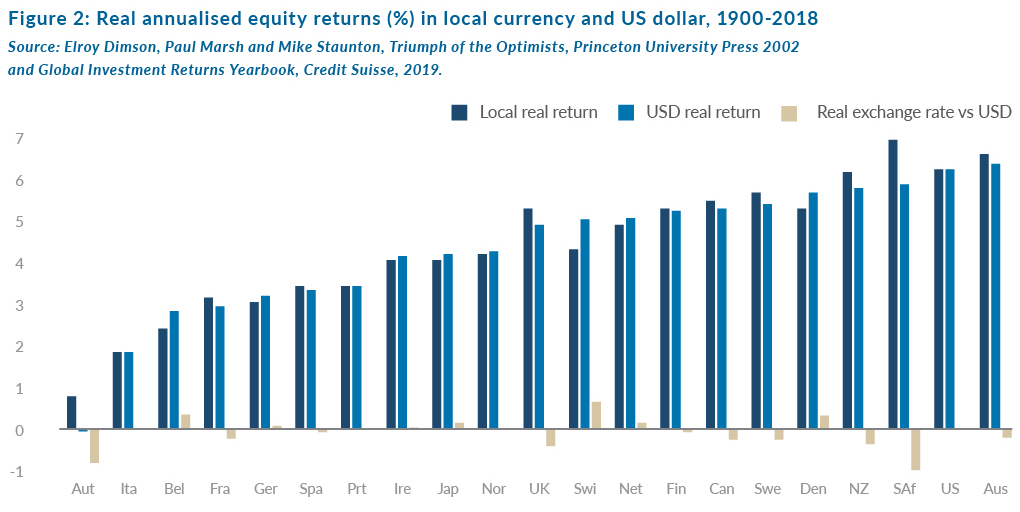

The local bourse has historically been one of the best places to generate returns, with the most recent edition of the global investment returns yearbook published by Credit Suisse and the London Business School showing that in local currency SA’s stock market is the best performing over the previous 118 years dating back to 1900.

Even in US dollar terms it’s the third-best performing stock market over that period.

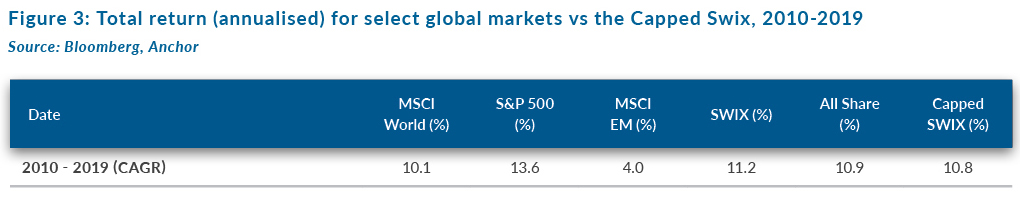

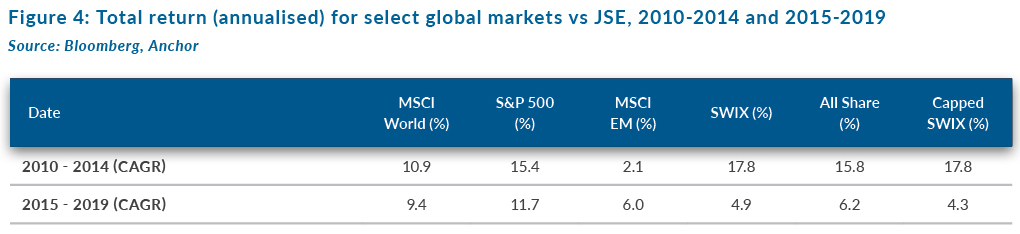

Certainly, more recently it hasn’t felt like the best place to be invested, though over the last decade its kept pace with major global benchmarks (and significantly outperformed its EM peers). So, the issue it seems is not really a lost decade, but just a tough last few years.

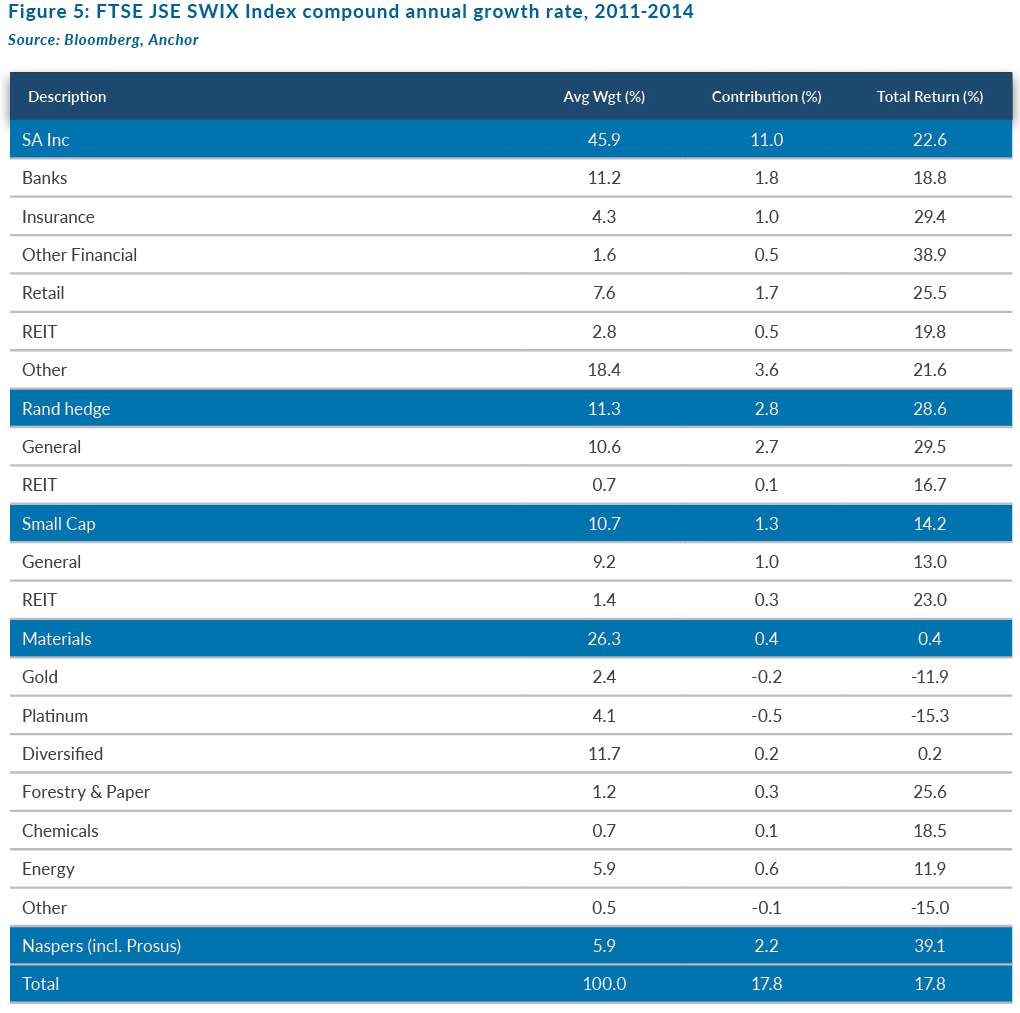

The composition of the local bourse has done a lot to mask the pain felt by domestic companies more directly exposed to the dire local economic growth malaise. In the first half of the decade, SA Inc. companies were up over 20% p.a. and small-cap stocks (also predominantly exposed to the local economy) were up 14% p.a. Commodity companies were the ones holding the local market back, particularly gold and platinum stocks. While Naspers was up about 40% p.a. in the first half of the decade it only averaged 6% exposure in the index, so it wasn’t as meaningful a contributor as it has become since then.

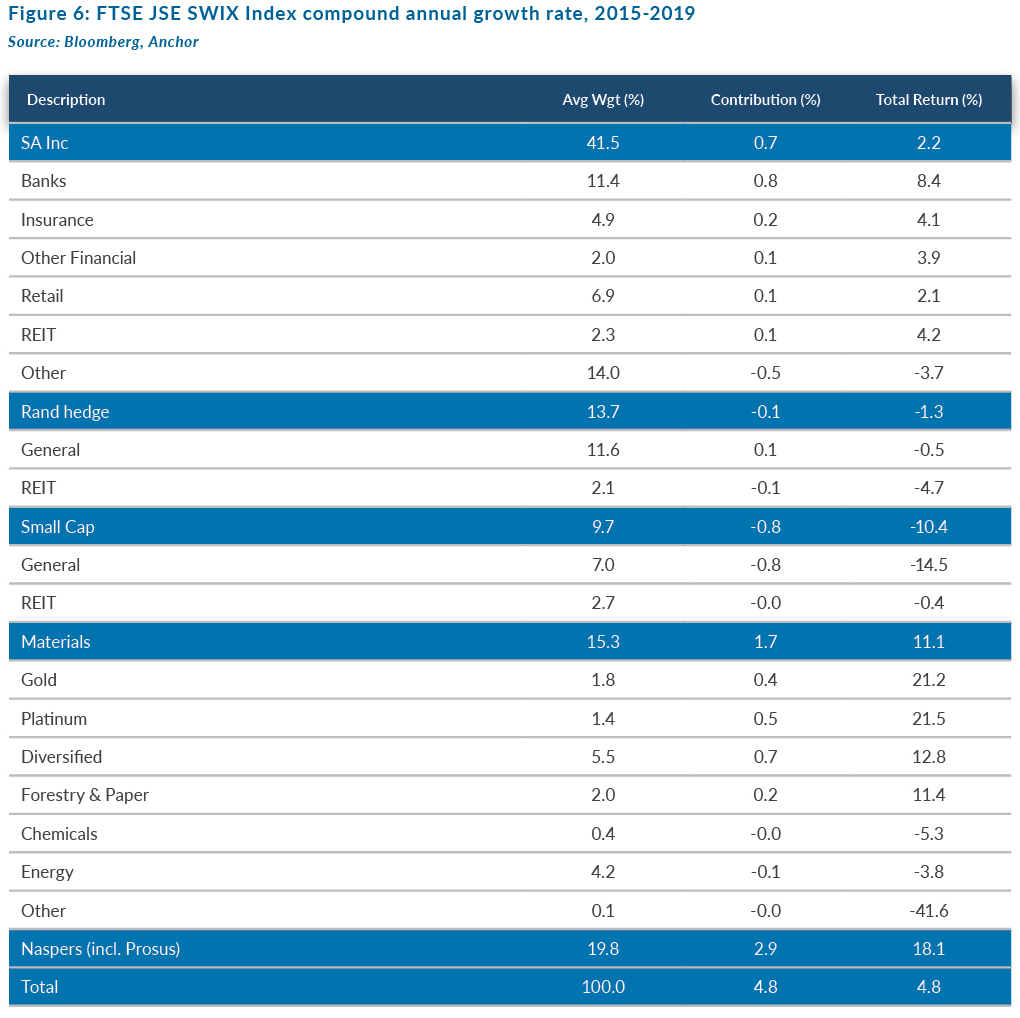

The situation basically reversed in the second half of the decade. Commodity companies delivered a third of the index returns, with gold and platinum companies up over 20% p.a. Naspers was up 18% p.a. (less than half of what it did in the first half of the decade), but it constituted a fifth of the index exposure and 60% of the index return in the second half of the decade. Small-cap stocks were disastrous, including a few that imploded (e.g. Tongaat and EOH) and Steinhoff who’s accounting scandal turned it into a small cap and wiped over 2% off the index return.

SA Inc. shares were up just over 2% p.a. for the latter half of the decade, with the banks the only sector to deliver inflation-beating returns (the aggregate bank returns were slightly flattered by Capitec, which was up 36% p.a. over that period).

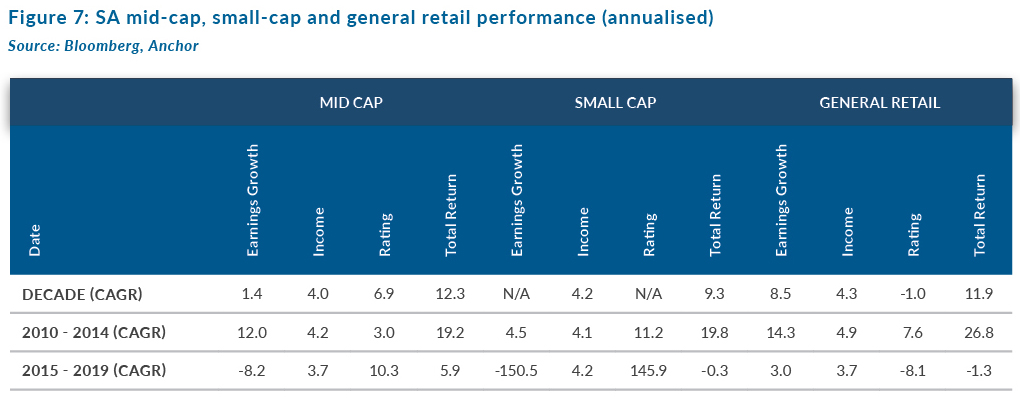

As can be expected in a five-year period, which saw the SA economy average only 0.9% p.a. of economic growth, the lack of earnings growth was the biggest source of pain for SA Inc. shares. Notably, mid- and small-cap shares saw earnings go significantly backwards over the period and general retailers eked out some barely positive earnings growth.

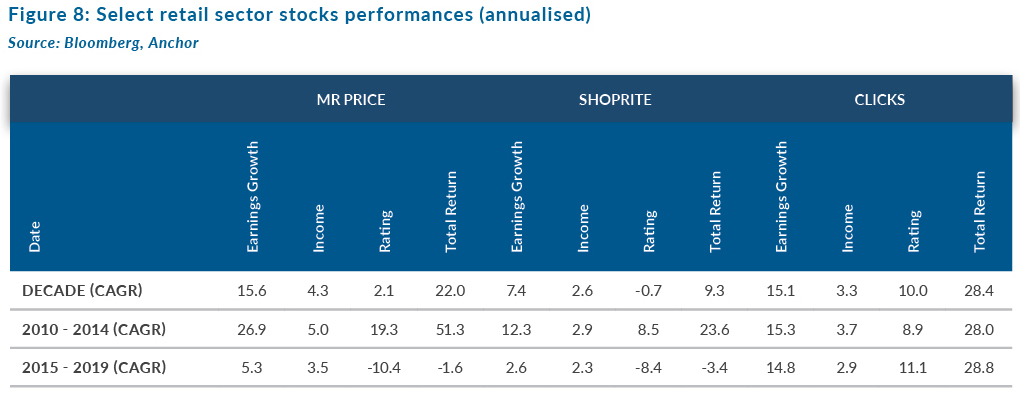

We note though that, within the retail sector, there were diverging fortunes, with the likes of Mr Price and Shoprite struggling to maintain positive earnings growth in the latter half of the decade, while Clicks continued to deliver, despite the environment.

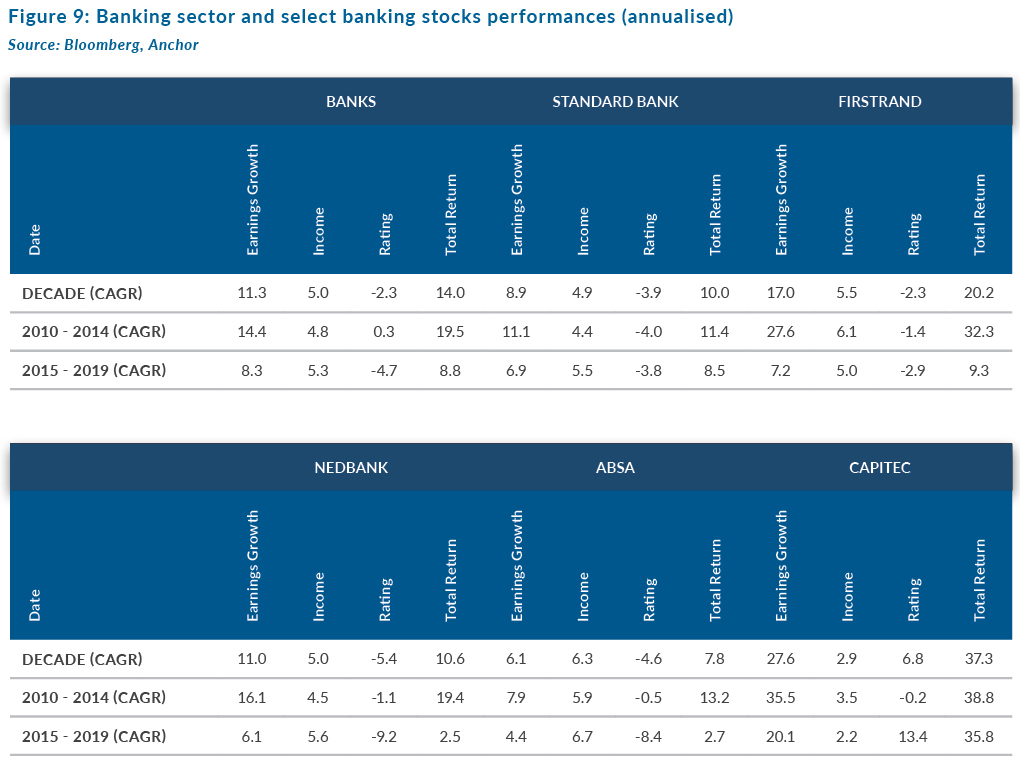

Banks did well to generate high single-digit earnings growth in the second half of the decade, not quite the mid-teens earnings growth from the first half of the decade, but decent under the circumstances. The fact that there has been a reasonable de-rating in the large bank shares in the last few years probably reflects investors’ scepticism of their ability to maintain that level of growth without a decent economic recovery.

So, we’ve seen what a struggle it’s been for domestically focussed SA companies in the latter half of the decade. It’s not been a Lost Decade, but the last half of it has been tough. That’s all in the past, the more important question is “where to from here?”. We refer to renowned behavioural psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, often in our research. He’s done some phenomenal empirical work on understanding the tricks our minds can play on us and, in finance, understanding those biases can help us make more rational decisions. He did some interesting experiments with patients going through colonoscopy procedures that helped him better understand “recency bias” – the propensity for our memories to place too much significance on recent painful experiences and ignore the entire experience. We certainly run the risk of making that mistake with local equities – the best-performing asset class going back to the turn of the previous century, but one of the most painful experiences for investors more recently.

For a recent example of the opportunity cost of capitulating after an unusually tough period, we only need to look at the last candidate for “Lost Decade” – the S&P 500 Index. If you had given up on the S&P 500 after the Lost Decade, you would’ve missed out on a more “normal” decade thereafter with mid-teen annual returns.