The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a pivotal institution in the global financial system, and it is particularly crucial for indebted countries, especially low-income nations. Established in 1944 in the aftermath of the Great Depression, the IMF aims to promote international monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty worldwide. For indebted and low-income countries, the IMF plays a multifaceted role that extends beyond mere financial assistance.

One of the primary functions of the IMF is to provide financial assistance to countries facing balance of payments problems. For low-income countries, which often suffer from inadequate foreign exchange reserves and high levels of external debt, IMF loans are a critical lifeline. These loans help stabilise economies by providing the necessary funds to meet immediate financial obligations, thus preventing default and the severe economic and social repercussions that accompany it. By doing so, the IMF helps indebted countries avoid crises that could lead to severe economic contractions, hyperinflation, and social unrest. The IMF’s role, however, goes beyond financial aid. It offers invaluable policy advice to address the root causes of economic distress. For low-income countries, this guidance is crucial. These nations often face structural challenges such as inefficient public sectors, inadequate tax systems, and underdeveloped financial markets. The IMF’s expertise in these areas helps governments implement reforms to improve fiscal management, enhance public sector efficiency, and foster a more conducive environment for economic growth. Although sometimes controversial due to their stringent nature, these reforms are essential for long-term stability and development.

The IMF conducts regular economic surveillance of its member countries, providing an early warning system to identify and mitigate potential economic risks. This surveillance is vital for low-income countries, which may lack robust domestic analytical capabilities. The IMF’s monitoring activities help these countries stay informed about global economic trends and their potential impacts. The IMF’s proactive approach involves identifying potential risks and providing guidance on how to mitigate these risks. This allows governments to take pre-emptive measures to safeguard their economies against external shocks, such as fluctuations in commodity prices or global financial conditions. In cases where indebted countries face unsustainable debt burdens, the IMF plays a crucial role in facilitating debt restructuring. By working with indebted countries and their creditors, the IMF helps negotiate terms that make the debt more manageable. This process often involves extending repayment periods, reducing interest rates, or even lowering the principal amount owed. For low-income countries, debt restructuring is often necessary to regain economic stability and restore growth prospects. The IMF’s involvement in this process provides credibility and reassurance, encouraging broader participation from creditors and fostering a more positive outlook for the future of these countries.

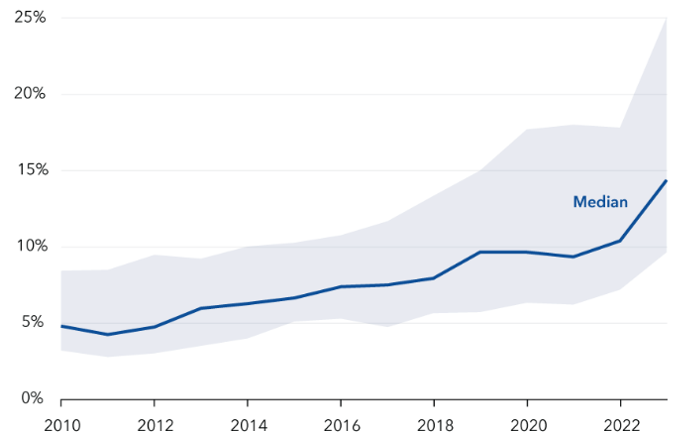

Positively, as we move further into 2H 24, there have not been any notable requests by a low-income country for comprehensive debt relief since Ghana more than a year ago. Despite this, vulnerabilities remain, with high debt servicing costs a growing challenge for low-income countries. Financing pressures due to relatively high interest payments and the pace at which low-income countries need to repay debt are straining budgets. While the burden varies significantly across countries, the latest IMF forecasts show it is roughly two and a half times higher than a decade ago. For a typical low-income borrower, the debt share has increased to around 14%, up from c. 6%, and in some economies, it has surged to as high as 25% from c. 9%.

Figure 1: External debt service to revenues

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2023.

Revenues excluding grants. Data for 2023 are projections. The shaded area represents the interquartile range.

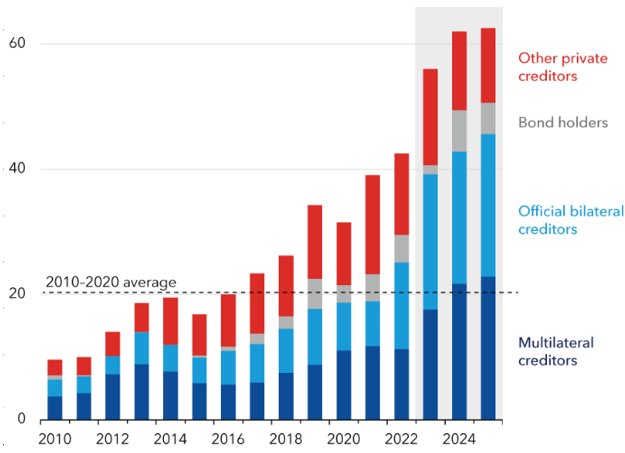

Notably, low-income countries face substantial debt repayments due over the next two years, needing to refinance approximately US$60bn of external debt p.a.—about three times the average from the decade leading up to 2020. Competing demands for financing, particularly from advanced and emerging market (EM) economies addressing climate change, raise the risk of a liquidity crunch, where countries struggle to secure adequate financing at affordable costs. This situation could potentially trigger a destabilising debt crisis.

Figure 2: Principal payments due to foreign creditors (US$bn)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2023.

Note that data for 2023 and beyond are projections.

Many factors have driven this growing financing challenge in recent years. One key factor is higher government borrowing and deficits to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and other external economic shocks. This has increased the level of debt and, consequently, the cost of servicing it. It is encouraging, however, that this trend is reversing as countries bring primary deficits back in line with pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, central banks have significantly raised borrowing costs to combat inflation, making it more expensive for governments to incur new debt or refinance existing obligations. While central banks may have paused rate hikes, the timeline for potential cuts remains uncertain, contributing to volatile financial market conditions. Over the past decade, low-income countries have increasingly turned to the private sector for financing, with about one-third of their funding coming from private creditors, compared to one-fifth in the previous decade. This shift reflects a slowdown in financing from multilateral development banks (MDBs) and official development assistance (ODA) agencies from 2020 to 2022 relative to borrowing needs. Consequently, this change has raised financing costs and heightened vulnerability to global financial shocks.

Building resilience in response to these trends requires decisive action from countries. While some have made progress, many are falling behind, particularly in efforts to increase revenues by broadening the tax base, reducing tax exemptions, and improving tax administration efficiency. For example, the average Sub-Saharan African country raised only 13% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in revenues in 2022, compared to 18% in other emerging economies and developing countries and 27% in advanced economies. Nevertheless, reforms take time to yield results, so countries must actively seek to mobilise funding at lower costs, primarily through grants. For some, this may involve seeking assistance from the IMF. When countries struggle with debt, timely restructuring becomes essential to mitigate damage. Delays in restructuring can worsen distress by complicating adjustments and increasing costs for debtors and creditors. Prolonged waits lead to job losses and rising poverty for individuals, while creditors see their losses grow as they wait for recovery. It is a lose-lose situation. While some sovereign restructurings have faced significant delays in recent years, the IMF has done well to accelerate the process.

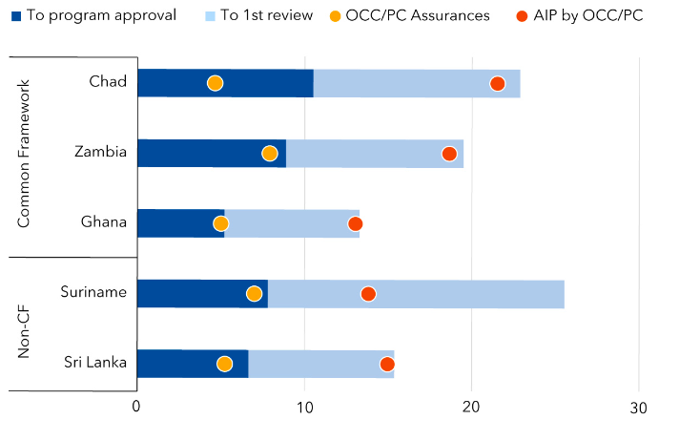

The Common Framework, which unites creditor countries to facilitate necessary debt restructuring, has begun to yield positive results. This is achieved by shortening the time frame between the IMF staff-level agreement—a critical step toward securing an IMF programme—and providing financing assurances from official creditors required for programme approval. As a result, the IMF can more rapidly extend much-needed financial assistance to the country in question. For instance, Ghana’s agreement this year took five months to complete these steps, approximately half the duration required for Chad in 2021 and Zambia in 2022. Furthermore, negotiations with Ethiopia are expected to proceed more swiftly, potentially aligning with the customary timeframe of two to three months.

Figure 3: Timelines from IMF staff-level agreements in several months

Source: IMF

Note: Suriname’s first review was combined with the second review due to other circumstances. OCC/PC Assurances = Official Creditor Committee/Paris Club Assurances. AIP by OCC/PC = Approval in principle by Official Creditor Committee/Paris Club.

These improvements are partly a result of stakeholders gaining more experience collaborating, including with non-traditional official creditors such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia. Previous cases faced challenges related to creditor coordination; however, increased familiarity with the process has enabled parties to better anticipate outcomes, foster trust, and more easily navigate what were once significant obstacles. Additionally, there has been progress in expediting debt restructuring for EMs outside of the Common Framework. For example, Sri Lanka’s case progressed more rapidly than Suriname’s in 2021, reflecting enhanced creditor coordination and a better understanding of necessary safeguards and assurances.

It is important to bear in mind that the involvement of the IMF often serves as a catalyst for additional financial support from other international institutions and bilateral donors. For low-income countries, securing IMF support can enhance their creditworthiness and signal to other potential investors and donors that the government is committed to implementing sound economic policies. This catalytic effect is essential for mobilising the financial resources needed for development projects, infrastructure improvements, and social programmes. Ultimately, the IMF’s work with indebted and low-income countries is geared towards promoting poverty reduction and sustainable development. By providing financial stability, policy advice, technical assistance, and facilitating debt restructuring, the IMF helps create an environment where these countries can focus on long-term development goals. Improved economic stability allows governments to invest in critical areas such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure, which are fundamental to reducing poverty and improving living standards.