Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), has made significant changes to its monetary policy, bidding farewell to a range of unconventional monetary policy tools, such as the negative interest rate policy (NIRP), yield-curve control (YCC), and quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE), marking the end of an era in extraordinary monetary easing. These tools were key components of the BoJ’s extensive monetary policy approach to stimulate inflation following the plunge in asset prices in the 1990s. Although none of these tools led to visible inflation, Japan’s new inflationary landscape has allowed the BoJ to retire some of its measures, marking a historic policy shift from a complex and overly accommodative stance to a simpler approach. In this article, we examine the monetary policy shifts given Japan’s new inflationary landscape and the recent currency intervention.

Global implications of the BoJ policy shift

The BoJ’s policy shifts are of global interest because Japanese investors are significant exporters of capital. Since the 1990s, Japanese investors have purchased substantial US and European government bonds. To contextualise the scale of foreign bonds bought by Japanese investors, it is notable that Japan is the largest foreign holder of US government bonds, owning over US$1trn worth. Therefore, any shifts in Japan’s monetary policy towards monetary tightening—even if widely telegraphed—will always be accompanied by fears that Japanese investors might lose interest in foreign bonds, as rising Japanese government bond (JGB) yields could lure investors back to domestic bonds.

The time had come to shift away from NIRP, QQE and YCC – the new inflationary landscape

In March 2024, the BoJ took its first step towards normalising monetary policy by ending NIRP and raising its policy interest rate by 10 bps, from -0.1% to 0.0%–0.1%. This marked the first policy shift towards monetary tightening in 17 years. Subsequently, the central bank decided to halt and, in some cases, taper QQE measures. This occurred after the BoJ had gradually backed away from YCC by allowing the yield on 10-year JGBs to fluctuate more freely.

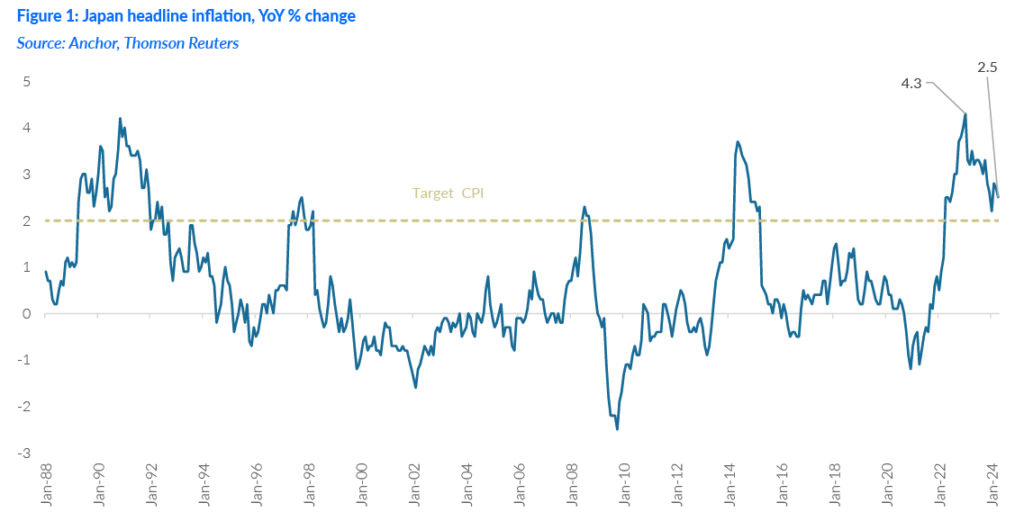

The BoJ’s policy shift to a simpler approach was no surprise. The economic fundamentals were supportive, and the shift was well-telegraphed through commentary and a gradual move away from YCC. The Japanese economy has faced deflationary pressures for years and has finally seen healthy inflation in recent months (Figure 1). This inflation has been driven by a combination of global inflation induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, higher wage growth, and a depreciating currency. By January 2023, headline inflation in Japan had jumped above 4%, the highest level since the 1980s and well over the 2% target (Figure 1). Inflation has since remained well above the BoJ’s target.

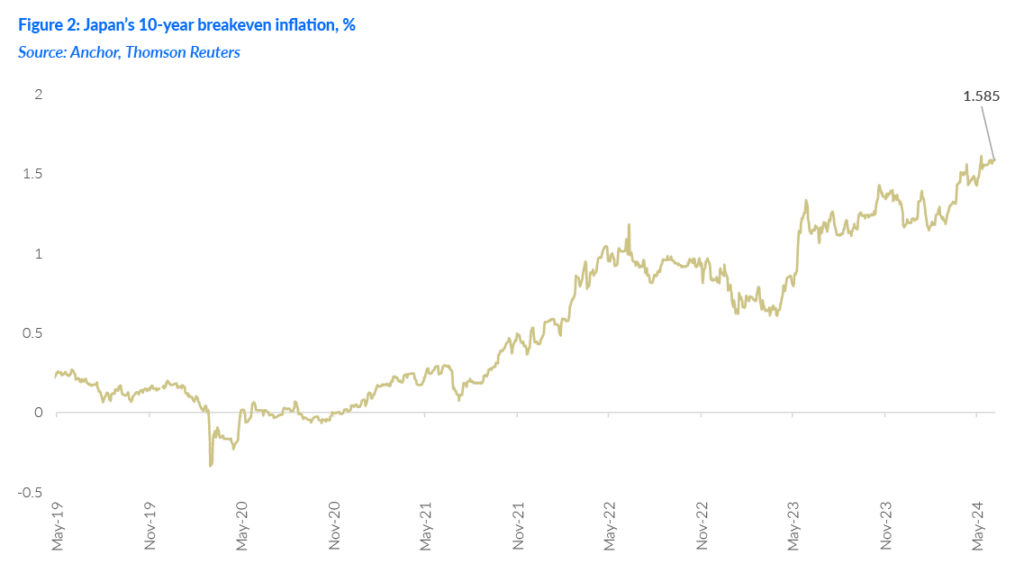

A key question for future BoJ policy direction is where Japan’s inflation will stabilise post-pandemic. Although inflation moderated throughout 2023, and further moderation is quite possible, market-based inflation expectations in Japan have been re-anchored at more favourable levels, fuelled by higher wage growth and excessive currency depreciation (Figure 2). This marks a significant departure from the near-zero percent trend observed over the past three decades. The pandemic’s global inflationary impact has undoubtedly catalysed Japan’s new inflationary landscape. However, judging from recent statements by the BoJ, accommodative conditions are still necessary for Japan. The pace of upcoming interest rate hikes will depend on incoming economic data and how confident the BoJ is that post-pandemic inflation is stable at around 2%.

The currency has a yield problem the BoJ cannot easily fix

Why is the yen depreciating?

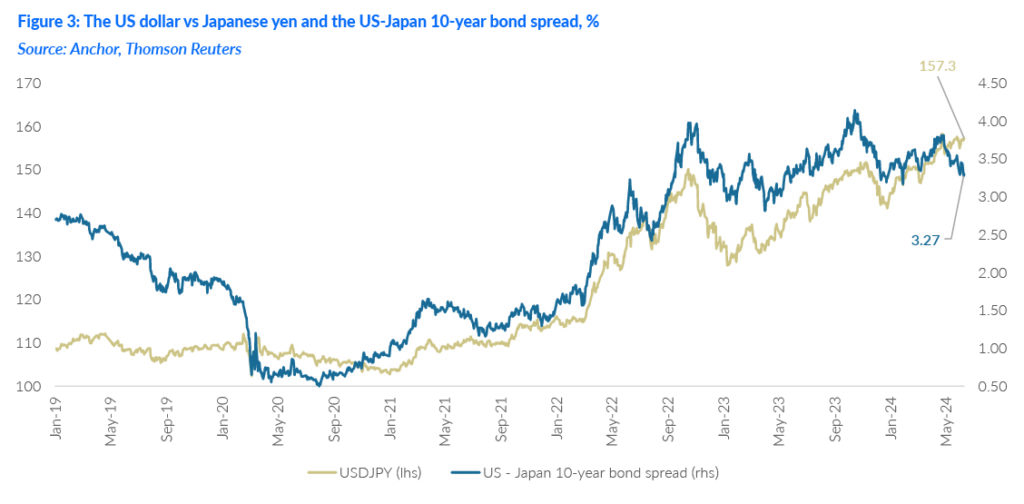

The value of a country’s currency rises and falls relative to other currencies in line with the laws of supply and demand. Japan’s currency, the yen, has depreciated significantly against the US dollar to levels last seen in the 1990s. The yen is similarly weak against other major currencies, such as the euro and the British pound. The yen is typically a funding currency for carry trades, making its exchange rate highly correlated with the US-Japan bond yield spread (Figure 3).

A currency carry trade is a strategy that involves borrowing money in a currency with a low interest rate and investing it in a currency with a higher interest rate. This strategy aims to profit from the difference between the interest rates, known as the interest rate differential. The interest rate differential between the US and Japan is the main driver of the yen’s weakness against the greenback. The interest rate in the US is above 5%, while the interest rate in Japan remains near zero. Running unhedged positions even boosted carry trade returns. This gap in interest rates reflects the different inflation environments in the two countries. While Japan has struggled to get prices and wages to rise for decades, the US has been battling to bring prices down amid robust economic growth.

In addition, rapidly changing market expectations regarding the US Fed’s monetary policy are also resulting in yen selling. Market expectations for a near-term narrowing of the US-Japan interest rate differential are rather pessimistic. The US economy is showing good growth momentum, a resilient labour market, and lingering inflationary pressures. The Fed and markets have scaled back expectations of interest rate cuts in 2024 compared to expectations at the start of this year. With the Fed not in a hurry to cut interest rates (gradual easing cycle) and the BoJ not in a hurry to raise interest rates (gradual tightening cycle) in the near term, the interest rate differential will likely remain wide. This exacerbates carry trades, leaving the yen weaker and investors (those with exchange rate risk tolerance) benefitting from running unhedged positions.

Why is excessive currency depreciation a problem for Japan?

Japan is a net importer of many goods, including agricultural products and crude oil. Therefore, a weak currency increases import costs, squeezing Japanese household budgets, particularly for food and fuel. Despite the BoJ not having a mandate to manage the currency, a weak yen complicates its objective of maintaining price stability, as it is inflationary.

What can Japanese authorities do to contain yen depreciation (yen intervention)?

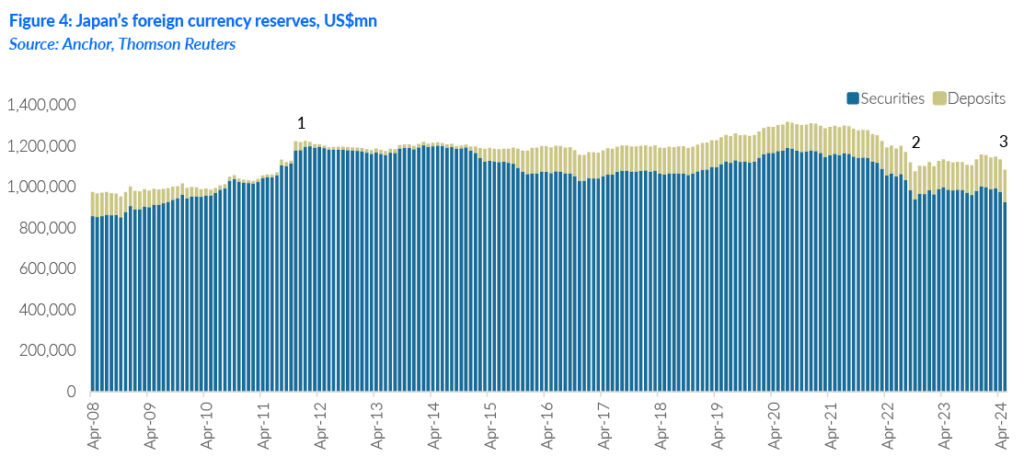

Japan’s fiscal and monetary authorities can employ two main economic levers to contain yen depreciation: buying the yen through foreign exchange interventions or raising interest rates – monetary tightening. The latter is not a near-term solution, as we previously discussed the BoJ’s cautious, data-dependent approach towards increasing the policy rate. This leaves Japanese authorities with currency intervention operations. Japan’s fiscal authority, The Ministry of Finance (MoF), decides whether to intervene in the currency market, and the BoJ (monetary authority) does the buying or selling. Japan has a history of conducting currency interventions. In 2022, it intervened in the currency market several times by selling US dollars to buy yen (“2” in Figure 4). Similarly, in 2011, the BoJ sold yen and bought US dollars (“1” in Figure 4).

In May 2024, a sharp, sudden surge in the yen’s value prompted speculation that Japanese authorities had intervened in the currency markets to halt the yen’s depreciation as the US dollar/Japanese yen (USD/JPY) pair approached the JPY160/ US$1 level. Central banks aiming to prevent their currencies from depreciating too rapidly typically intervene by selling US dollar-denominated assets from their foreign currency reserves and purchasing their currency with the proceeds. Japan possesses a substantial pool of foreign currency reserves, primarily denominated in US dollars, which it can utilise to buy yen, although this resource is not unlimited. As of the end of May 2024, Japan’s foreign currency reserves, which include securities and deposits, totalled US$1.08trn (Figure 4).

Japan’s holdings of foreign securities decreased by US$50.4bn in May 2024, indicating that the government likely financed most of its recent currency intervention by selling US government bonds and other foreign securities (“3” in Figure 4). As US government bond prices rose and yields declined in May, the market value of Japan’s foreign securities would have increased if assets were left untouched. Foreign deposits saw a slight increase, suggesting they were not a significant source of intervention funding. The decline in foreign security holdings suggests that Japanese authorities used similar funding sources for currency intervention as they did in 2022 when they spent US$62bn to strengthen the yen on three occasions.

The impact of currency interventions is generally short-lived and does not reverse fundamental dynamics; these interventions are typically used to “buy time.” The April/May currency intervention initially moved the USD/JPY pair from around JPY158-JPY153/US$1. However, today, the currency pair has almost entirely reversed course following the intervention, with USD/JPY trading back up, just below the JPY158/US$1 level.

To alter the yen’s trajectory, either the BoJ would need to promptly adopt a more hawkish stance (which seems unlikely), or the Fed would need to clearly signal potential interest rate cuts (also doubtful). Ultimately, this problem can only be addressed by time. Currency interventions provide the BoJ with the necessary time to assess incoming economic data before deciding on future policy direction. Fortunately for Japan, the size of its foreign currency reserves suggests that it still has ample ammunition to conduct more of these currency operations if the USD/JPY pair approaches the JPY160/US$1 psychological level again soon, buying additional time if necessary.

Conclusion

The BoJ is trying to balance the Japanese economy in this new inflationary environment. While economic fundamentals supported the BoJ’s decision to phase out a range of unconventional monetary policy tools, the central bank still requires additional supportive economic data to be confident that future inflation will stabilise around the 2% target. For investors, a more normalised Japanese bond market is expected to offer a higher risk premium and modestly higher yields in response to ongoing policy adjustments and the transition of Japanese government bonds back to market-driven forces. JGB yields have tracked higher in recent months, with 10-year JGB yields approaching 1%. This presents fresh opportunities for investors who are cautious about this space over the past decades. Institutional flows into Japanese bond markets are also anticipated to increase in the short to medium term.