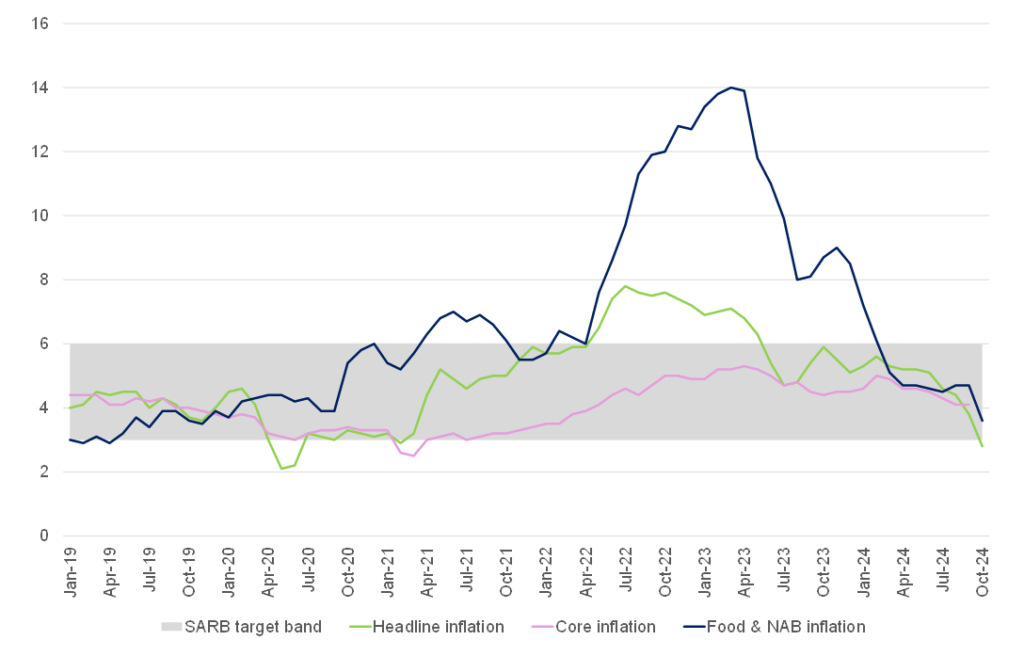

October inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), revealed a continuation of the disinflationary trend, with headline inflation printing at 2.8% YoY. This represents a sharp decline from the 3.8% YoY recorded in September. October’s print is the lowest since June 2020 (during the COVID-19 pandemic), when the rate was 2.2%. Falling fuel prices remain the key driver behind the recent slowdown. Between September and October, petrol and diesel prices dropped by 5.3%, bringing the annual fuel inflation rate to -19.1%. In October, the inland price for 95-octane petrol stood at R21.05, its lowest since February 2022, when it was R20.14.

Core inflation (which excludes volatile food and energy prices to reflect underlying inflationary pressures) eased to 3.9% YoY in October, down from 4.1% in September, signalling weaker demand across most categories. Household contents and equipment continued to experience deflationary trends, with appliance prices falling further to -2.7% in October, compared to -1.7% the previous month. The slowdown extended to other sectors, including healthcare and transportation, with vehicle prices significantly contributing to the broader deceleration. The drop in core inflation, now below target, underscores the persistent financial strain on households.

Figure 1: SA inflation, YoY % change

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

Inflation in food and non-alcoholic beverages has slowed significantly, easing to 3.6% YoY in October from 4.7% in September. Overall food inflation dropped to 2.8%—its lowest level since May 2019—as the effects of the El Niño phenomenon diminished. This decline was widespread, with notable decreases in categories such as sugar, sweets, desserts, bread and cereals, and meat, which had previously driven prices higher. Vegetable prices, a major contributor in September, also cooled considerably. Tomato prices, for example, fell sharply from a 25% YoY increase to just 5.8%, while potatoes and sweet potatoes dropped from YoY spikes of 14% and 17.6% to 3.4% and 7.2%, respectively. The waning impact of the earlier black frost has further supported this broad deceleration in food inflation.

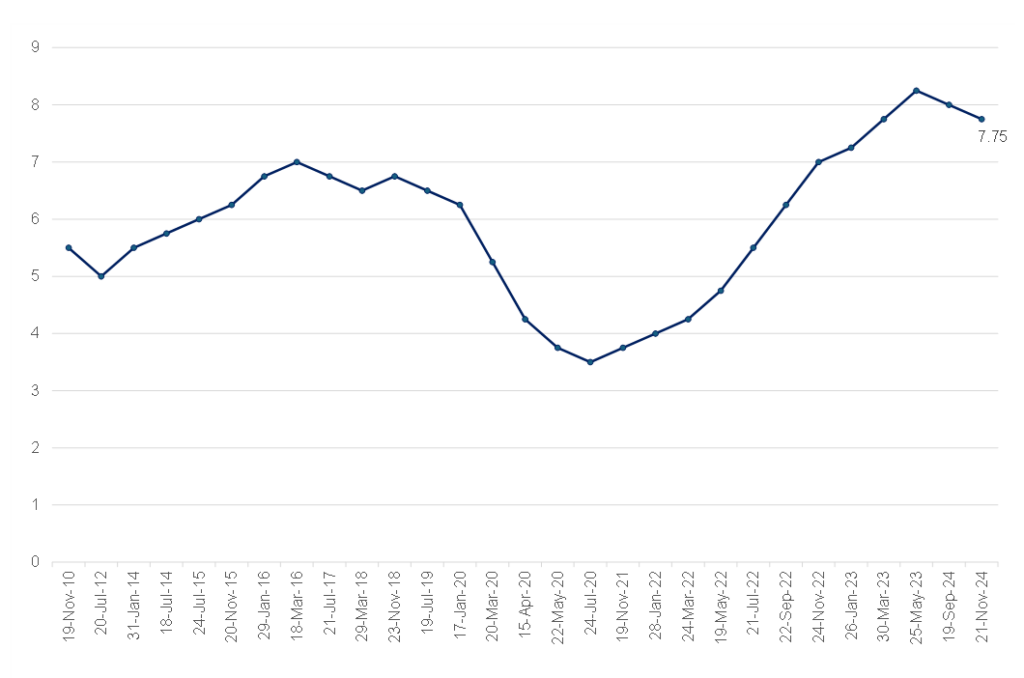

Against this backdrop, in line with expectations, the South African Reserve Bank’s (SARB) Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to lower the repo policy rate further by a cautious 25 bps to 7.75% p.a. at its 21 November meeting. The prime lending rate is now at 11.25%. Despite the lower-than-expected inflation print for October, it is important to remember that since the SARB’s last meeting in September, the global macroeconomic environment has grown increasingly challenging. The US dollar has strengthened against most currencies, including the rand, while longer-term interest rates have risen in the US and globally. Expectations for short-term rates have also shifted higher. Monetary policy in major economies remains firmly restrictive, even as headline inflation has moderated. This moderation has created limited room for central banks to pause or ease rates. In addition, over the past two months, renewed inflationary pressures and heightened uncertainty have narrowed this policy space significantly. Core inflation remains above target in several economies, raising the risk of policy reversals should price pressures persist. The global landscape suggests central banks face a delicate balancing act, with tightening financial conditions and persistent inflationary risks complicating their ability to stabilise growth and prices simultaneously.

As such, SA’s risk outlook requires a cautious approach – hence the moderate 25-bp rate cut. Furthermore, looking ahead, we view the October CPI print as marking the low point in this inflation cycle. While inflation is expected to remain subdued over the next three months, the trajectory will likely trend upward thereafter. High base effects from last year will continue to influence the data in the near term, keeping inflation readings relatively muted despite a gradual increase. However, beyond this period, several factors could shift the inflation landscape. The weakened rand is expected to play a growing role, particularly as it increases the cost of imports. Additionally, pressures in the food sector are intensifying. Below-average harvest estimates for key crops raise concerns about price increases for staples such as bread and cereals. This, in turn, could lead to higher meat prices, amplifying inflationary pressures across the broader food basket.

Energy prices also remain a critical area to watch. Eskom’s proposed 36.15% electricity tariff hike poses a significant risk to administered prices, potentially fuelling inflation. Meanwhile, ongoing volatility in global fuel markets adds further uncertainty. The rand’s sensitivity to global risk aversion remains a persistent challenge, especially in the context of geopolitical tensions or shifts in international monetary policy. Together, these factors suggest a more complex future inflationary environment, requiring careful monitoring of domestic and global developments. Positively, however, the SARB’s improved GDP growth forecast, now reaching 2% in 2027, has provided increased credibility to the SA reform agenda.

Figure 2: The history of the SARB MPC’s repo rate changes, %

Source: SARB, Anchor