In this note, we look at some positive stories coming out of South Africa’s (SA’s) agricultural sector and we also give our preliminary thoughts on the impact of COVID-19 on the agricultural sector in general.

SA’s farm economy (looked set to?) recover in 2020

The local farming economy (down 6.9% YoY) recorded a poor showing in 2019 – its second year of contraction. The output of various crops and horticultural produce declined notably last year due to the drought, while livestock was negatively affected by an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. However, initially, 2020 looked set for a far more positive showing as improved weather conditions led to an increase in summer crops area plantings and the prospect of higher yields. Recent Crop Estimates Committee data forecast that SA’s 2019/2020 summer crops production could increase by 26% YoY to 16.8mn tonnes. This would mean that it is the second-largest summer crops harvest (after the 2016/2017 crop) on record. Furthermore, wine grape production is also set to increase in 2020, and there is significant optimism around the 2020 harvest in the fruit industry. As a result, the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa (Agbiz) forecasts a minimum 5% YoY recovery for the SA farm economy.

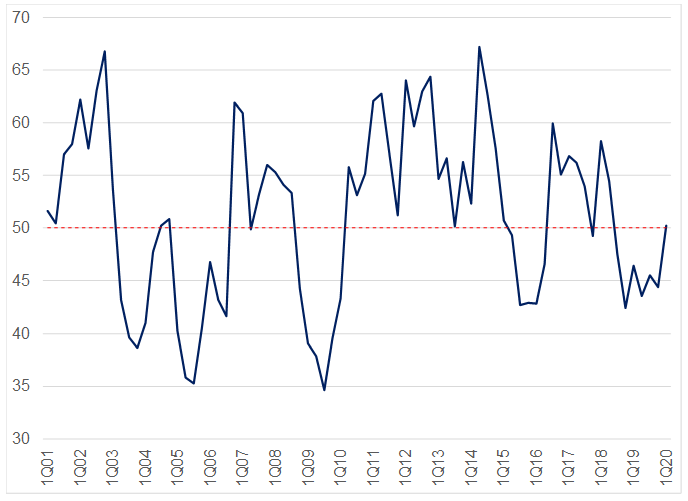

However, we note that two factors remain a concern (and should be monitored closely): 1) the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19); and 2) foot-and-mouth disease in the domestic red meat market. Whilst COVID-19 is impacting global demand and supply chains (the extent of which is difficult to quantify, thus far), the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak has led to a ban on SA livestock-products exports since the end of 2019. Conversely, the Agbiz/IDC Agribusiness Confidence Index (historically a good indicator of the growth path of the SA agricultural sector) has largely printed downwards in recent quarters – primarily due to policy uncertainty (i.e. land expropriation without compensation [EWC] etc.). It remains in contractionary territory, having eased by 44 points in 4Q19. This was below the neutral 50-point mark, indicating that agribusinesses remain downbeat about local business conditions. We note that the index is essentially a survey consisting of 10 different sub-indices, therefore a reading at the neutral 50-point mark or above implies that agribusinesses were relatively optimistic about business conditions, below they are pessimistic.

Figure 1: Agbiz/IDC Agribusiness Confidence Index performance

Source: Agbiz Research

Nevertheless, overall, the expected improvement in the summer crop and horticulture harvest will bring some much-needed optimism and confidence to the agricultural sector in the upcoming months. However, it is important to remember that any changes in the agricultural policy environment (and how these are subsequently perceived by agribusinesses), generally influences confidence levels faster than one can observe month-to-month, as the sector is guided by seasonal output levels.

Food, inflation and the threat of COVID-19

With SA’s agriculture sector being largely export-orientated (exports totalled US$9.8bn in 2019), the potential for disruptions due to global value-chain volatility is significant. Asia (the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak) accounts for a quarter of SA’s agricultural exports and the commodities most exposed to the Asian market are wool, fruit, grains, beverages, vegetables and red meat. Naturally, there are two channels to consider when attempting to calculate the potential implication of the virus on the SA agriculture sector – the supply side and the demand side. First, regarding the supply side of the aforementioned products, SA’s exports to Asia is generally in good shape, as discussed above. Furthermore, with the production of wine grapes and the fruit sub-sector set to increase in 2020, overall there is a healthy supply of products to export to the global market. Therefore, any near-term decline in exports would be a function of softening demand rather than supply related issues. Second, with China and large parts of Asia having been in a relative lockdown, the demand for production inputs will be negatively impacted. In addition, the longer employees are unable to work (and thus the increasing likelihood that some employers will stop paying their employees), the greater the implication for consumer demand – bearing in mind that SA’s agricultural exports are worth c. $2.5bn p.a. In addition, Asia is an important agricultural market not only to SA but for the world. The top-15 importers account for nearly 60% of the world’s agricultural imports, of which a quarter goes to Asia (mainly China, Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong). With COVID-19 now having Europe firmly in its grasp (another important agricultural export destination for SA), the potential for further risk to the recovery of SA’s farm economy remains significant.

The outbreak of COVID-19 is already leading to significant changes in the way we live our lives, thus raising serious concerns ranging from health safety, economic conditions to essential food supplies. In the UK, US and parts of SA we are starting to see empty shelves as consumers stockpile for fear of disruptions to global food chains and quarantine measures. This has given rise to questions as to whether SA could experience food shortages in the near- to medium-term. We remain doubtful that this will be the case, at least on a national level for most food products. SA is generally a net exporter of agricultural and food products, in addition to the forecast abundant harvest of staple grains and fruit in 2020.

Nevertheless, SA does depend on imports for essential food products such as rice, wheat and palm oil. Key palm oil suppliers are Indonesia and Malaysia. The typical rice suppliers are Asia and the Far East (countries including Thailand, India, Pakistan, China and Vietnam), some of which are hard hit by the pandemic. In the case of wheat, most of our imports come from Germany, Russia, Lithuania, the US and the Czech Republic – some of these countries have also been severely impacted. In the unlikely event of shortages occurring, we believe that this will be due to logistical bottlenecks in shipping rather than a decline in local and/or global supplies. Local grocery stores are now starting to place restrictions on the quantity of products individuals can buy in the attempt to limit panic stockpiling. The government has also enacted strict regulations with regards to unfair price hikes in order to counteract any opportunistic profiteers.

SA’s food price inflation accelerated to 4.2% YoY in February 2020, from 3.7% YoY in the previous month. This uptick was mainly underpinned by a rise in the prices of meat; milk, eggs and cheese; oils and fats; and vegetables. However, what really drives the direction in food price inflation are developments in the grains, meat and fruit markets. These three food categories account for nearly two-thirds of SA’s food price inflation basket. We highlight that the outlook for SA’s grain production is positive, while local maize production is estimated to increase by 35% YoY to 16.0mn tonnes, according to the latest forecasts from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). This could be the second-largest maize harvest on record after the 2016/2017 season (which recorded a 16.8mn tonne harvest for total maize). Furthermore, global wheat production (of which SA is a net importer), is set to rise by 5% YoY to 764.0mn tonnes. The outlook for fruit is also positive, with the citrus industry recently recording a 13% YoY increase in available supplies for export markets.

Amid the COVID-19 outbreak, especially within the EU and Asia region, any issues in supply chains would result in an increased supply for the local market, thereby lowering prices (a potential trend to consider). Naturally, that would be good for consumers, but the inverse can be said for farmers. Any upside pressure to the food inflation outlook would potentially come from red meat, following another foot-and-mouth disease outbreak at the end of 2019 and a possible slight uptick in poultry product prices on the back of government’s recent import tariff adjustment.