On 20 November, rating agencies Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s) and Fitch Ratings (Fitch) lowered South Africa’s (SA) sovereign credit ratings deeper into junk status, while S&P Global Ratings (S&P) affirmed its ratings. The key driver behind these downgrades was how fiscal policy ineffectiveness will likely remain, complicating fiscal consolidation. Rating agencies have become impatient with the SA government regarding the pace of reforms and rising debt costs. In recent years, government has struggled to deliver positive fiscal outcomes, which is why the fiscal authority is battling for credibility with the rating agencies.

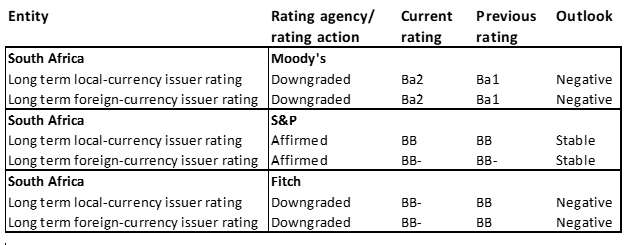

The timing of the downgrades caught many market participants by surprise, but the direction of the ratings action was broadly expected. Figure 1 shows the rating actions taken by the rating agencies on SA recently. Fitch’s and S&P’s foreign-currency ratings are now three-notches below investment grade (IG) and just one notch away from the B-rating category, where sovereign debt investment is deemed to be highly speculative and with a material default risk. The outlook on Moody’s and Fitch’s ratings remained negative, reflecting their concerns that further negative rating actions may be required soon.

Figure 1: Ratings agencies’ latest actions on SA, 20 November 2020

Source: Fitch, S&P and Moody’s

In this note, we discuss the general core pillars considered by rating agencies when assessing SA’s credit risk. We highlight that, we understand each rating agency uses its own criteria (different variables) to assess a sovereign’s creditworthiness, but their overall assessments are largely centered around the following four core pillars:

- Economic strength.

- Institutional and governance strength.

- Fiscal strength.

- Monetary and external strength

Economic strength

SA entered the COVID-19 pandemic with a weakening economic position. The country’s real GDP per capita has been contracting since 2015, while real GDP registered growth at below 1.5% over the same period. Relative to its emerging market (EM) peers, SA’s economic growth remains well below its peers on a per capita basis.

Like many economies globally, SA’s economy is facing a severe COVID-19-related downturn in 2020. Strict lockdown measures, engineered by government, and the global fallout of the pandemic has led to the local economy shrinking by c. 17.1% YoY in 2Q20 – a record low. Lockdown measures were somewhat eased during 3Q20 and the subsequent economic data prints suggest a recovery is on its way. Nevertheless, despite an expected 2H20 growth rebound, GDP is still widely forecast to contract by between 7% and 9% YoY in 2020. Due to base effects, growth in 2021 is expected to surge by c. 4% YoY but then significantly slow down again to c. 2.5% YoY in 2022. Despite the strong rebound in growth, the economy is still expected to remain below pre-pandemic GDP levels even in 2022.

In recent years, the fiscal authority’s strategy in promoting medium-term economic growth and addressing rising debt costs has largely rested on structural reforms. While the strategy remains in place, progress on structural reforms has been constrained by long-standing challenges, including unreliable electricity supply, a rising unemployment rate, elevated political tensions, and high inequality, which have resulted in reform inertia. The COVID-19 pandemic shock, paired with unaddressed domestic issues, are likely to make it even more difficult for the government to implement structural reforms, thus elevating implementation risks.

With heightened implementation risks, expected economic growth in the medium term is likely to be low, continuing to complicate fiscal consolidation efforts. Overall, SA’s economic strength has not changed significantly, however, we do note that downward pressure is being exerted on it.

Institutional and governance strength

During the previous administration of Jacob Zuma, SA’s institutional and governance strength deteriorated significantly. The aforementioned administration damaged state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as Eskom and eroded fiscal policy effectiveness.

Following years of weakening government institutions, the current administration of President Cyril Ramaphosa appears to be slowly strengthening various aspects, including the establishment of commissions to pursue accountability and the recent arrests of several high-profile politicians and businesspeople in relation to state capture.

However, even with the current administration, the country still faces some of these issues such as SOEs like Eskom, Land Bank, and South African Airlines (SAA) continuing to drain the country’s fiscal resources. In terms of policy effectiveness, the fiscal authority has struggled to deliver positive fiscal outcomes, which has in turn resulted in persistently low growth, while growth-enhancing government plans such as the Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan (ERRP) lack implementation details and timelines. Notably, tensions within the governing African National Congress (ANC) are also obstacles standing in the way of reform implementation.

Policy effectiveness remains strong when it comes to monetary management and the judiciary.

The overall strength of the pillar is weak and fiscal policy ineffectiveness is likely to continue exerting downward pressure on this pillar’s strength.

Fiscal strength

The COVID-19 shock has intensified SA’s fiscal challenges including widening fiscal deficits, rising debt levels, and interest payments absorbing an increasing proportion of fiscal resources.

Fiscal deficits have been widening since 2017 (4.1% of GDP), with the fiscal deficit reported at 6.4% of GDP in 2019. The COVID-19-related economic downturn is increasing the fiscal deficit as the fiscal authority now forecasts a 15.7% of GDP fiscal deficit for 2020. Shrinking revenues, rising costs, and increasing interest payments are key drivers behind the widening.

Pre-COVID-19, SA’s debt-to-GDP ratio was already on an upward trend (FY15: 51%; FY19: 65%). This upward trend has uncomfortably steepened in 2020, intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic shock. The fiscal authority expects the debt-to-GDP ratio to reach c. 82% in 2020. Contextually, this means that SA’s debt bill will be c. R4trn at the end of 2020. The fiscal authority’s target is to only stabilise debt at c. 95% of GDP in 2025 – an uncomfortable expected debt bill of c. R6trn.

SA’s debt affordability is also deteriorating as interest payments are consuming an increasing proportion of revenue and GDP, which ultimately limits economic flexibility. This crowding out of fiscal resources is caused by rising debt levels and increased yields on longer-dated government bonds. The interest payments-to-revenue ratio registered at c. 10% in 2014, with the metric expected to reach 19% and 21% in 2020 and 2021, respectively. Interest payments-to-GDP registered at c. 3.5% in 2017, with the metric expected to reach c. 4.8% and 5.1% in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

Additional fiscal pressures are also coming from problematic SOEs as the latest round of SOE-support was announced in the 2020 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS), where SAA walked away with R10.5bn to fund its business rescue process, while the Land Bank got R7bn. Fiscal flexibility is further squeezed by sizeable contingent liabilities largely tied to struggling electricity utility, Eskom. The SA banking sector is highly regulated and is unlikely to pose significant contingent liability risks to the sovereign.

Positively, the projected fiscal consolidation is not premised on unduly optimistic revenue expectations or excessive tax hikes. Government’s strategy is to reduce spending growth. Most of government’s spending cuts are coming from the large and fast-growing public sector wage bill. In recent years, the public sector has enjoyed above-inflation pay increases. According to the 2020 MTBPS, government aims to limit the increase in the wage bill by c.1.8% in 2020, which is well-below inflation and the rate set under the current three-year agreement on public sector wages. Containing the growth of the wage bill has been something which the government has struggled to achieve in the past due to the country’s strong labour unions, and these negotiations are likely to not go without social opposition as the matter is currently being heard in the courts.

The overall strength of this pillar is significantly deteriorating. Achieving fiscal consolidation largely hinges on wage negotiations and the implementation of reforms.

Monetary and external strength

Financial outflows are the predominant external risk. In April, government debt markets experienced severe strains due to the pandemic shock and the exit of SA Government Bonds (SAGBs) from the FTSE World Government Bond Index (WGBI). This led to a sell-off episode and a fall in the share of non-resident investors holding SAGBs to 29% in October 2020 from c. 37% in December 2019. This also resulted in elevated SAGB yields.

The sell-off was so intense, monetary assistance came from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) in the form of an open-ended programme of government bond buying in the secondary market – to provide liquidity and promote smooth functioning of domestic financial markets. The central bank has a strong track record of acting in a prudent manner that is guided by market-based monetary instruments – credible monetary policy. Government debt has also shifted materially onto the local banks and other financial institutions’ books which shows the depth of SA’s financial sector.

Despite the decreased share of non-resident investors holding SAGBs, the large holding still poses a risk for fiscal financing and external stability. In terms of fiscal financing, the domestic capital market remains a reliable primary source for the government. In terms of external stability, notable shock absorbers include a fully flexible exchange rate regime (the rand is a free-floating currency and is considered an actively traded currency, accounting for c. 1.1% of global foreign exchange market turnover), low levels of external debt denominated in a foreign currency (11.8% of total debt end October 2020), and a resilient current account deficit (CAD).

This pillar’s strength seems to be balanced.

Conclusion

SA’s credit profile is constrained by persistently low economic growth and increasing fiscal pressures, including widening fiscal deficits and large and rising debt levels. Fiscal policy ineffectiveness is likely to remain, complicating fiscal consolidation. However, on the positive side, the country’s credit profile is supported by a credible monetary policy, a highly regulated financial sector, low external foreign currency-denominated debt, and deep capital markets.