Much has changed since South Africa’s (SA’s) initial 21-day lockdown was first announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa in March 2020. Perhaps the most important development is the realisation that, as a society, we can no longer hide from the COVID-19 and the focus needs to be on learning to live with the pandemic. This means changing the way that we think about the pandemic and improving our daily hygiene. Improved personal hygiene is good and, perhaps, if we look at it through a different lens, some good may yet come out of this otherwise dire situation. Below, we highlight some of the positive takeaways from the past few months:

- We as a nation, along with our government, have learnt that a controlled economy is neither pleasant nor is it viable.

- We are of the view that Ramaphosa’s position as leader of the ANC and the country has been strengthened and that his consensus-building approach is more of a personal style than it is an endemic weakness of his office. Perhaps the first of the VBS Mutual Bank looters’ arrests this week attests to this strengthened position.

- We have also learnt that government is not in a position to feed and employ the entire SA population and without private sector participation a humanitarian crisis will unfold in this country.

- Similarly, government has been forced to acknowledge that it lacks the financial strength and the technical skills to manage and control SA’s various industries. Instead, it will need to work with the private sector to grow our economy.

- Likewise, the government has been unwavering in its commitment towards an independent central bank. As a nation, we should take heart from this.

- We only seem to talk about those state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that are in trouble, yet no one is discussing the Airports Company of South Africa (ACSA). Here is an example of an SOE which was in the eye of the storm with a catastrophic loss of revenue for at least three months and yet ACSA has been able to hold itself together. ACSA has, in all honesty, outshone many private sector companies that have needed to rely on rights issues. Maybe, we should talk about the successes of some SOEs more often?

The lockdown has been a massive burden on society, the brunt of which was always going to be felt most by the impoverished and the disadvantaged. It was also always going to increase the inequality in SA and this will be felt for many years to come. Our tax system is already one of the most redistributive in the world, but it alone cannot address the scourge of inequality in this country. We need to have open dialogue about fair access to quality education, healthy family environments, dependency ratios, business opportunities and gender-based violence (GBV).

The most immediate impact of the lockdown is that when people do not buy goods and services, they also pay no VAT to government. Companies that earn no income, pay no income tax and workers who are furloughed do not contribute to the fiscus. Companies on the JSE that have had a three-month income hiatus have started to announce rights issues. This is not possible for our national government and instead government will need to look at how it manages its finances.

SA started the year in a very weak financial position. In our view, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni will announce that tax collection will be between R250bn and R300bn lower than previously expected, when he presents his supplementary or Special Adjustment Budget to Parliament on 24 June. In the short term, government will have no choice but to live on debt. The SA government is already borrowing nearly R1bn per day from the domestic market and it has also been forced to reach out to the IMF and other global organisations to raise cash. However, its current pace of borrowing is not sustainable and even our domestic market will, at some point, battle to finance government at the current pace of bond issuances. Simply put – SA needs to bring its reliance on debt down. This budget is not so much about how we balance the books in 2020, but rather about how we return to a sustainable footing in future.

Prescribed assets, where government forces the pension fund industry to buy government-backed securities such as bonds and equities using the savings of their clients, also comes up from time to time. However, we do not expect these to be announced. Most pension funds in SA are already overweight or busy moving overweight government bonds. If we look at Anchor Asset Management, for example, a requirement to hold 10% of our clients’ assets in government bonds is irrelevant in the short term because we already hold a significantly larger amount of SA government bonds. Instead, all this will accomplish is to give clients an incentive to invest with offshore asset managers rather than domestic managers. Prescribed assets would be unlikely to raise additional finance for the government and is instead more likely to act as a catalyst for the saving pool to leave our shores. Many individuals will simply stop their pension fund contributions and those that can will withdraw.

The finance minister is in a difficult position. He knows that South Africans are heavily taxed and that increasing the overall tax burden will be difficult. Optically playing with the maximum marginal tax rate, capital gains tax (CGT) inclusion rates or inheritance tax might appease the masses, however, it will in reality raise very little additional revenue and just serve to irritate those who are still paying tax in SA.

This means that Mboweni has no choice but to use the budget to scare our Parliament into understanding how dire the situation is. We should expect a harsh message that is designed to bring home the truth of the situation to members of Parliament, most of whom do not have a degree in economics or accounting and therefore do not intuitively understand what the numbers mean. It is indeed going to be a shock to their collective system.

The finance minister has communicated that some spending will be reprioritised away from certain departments. This means that we will likely see many unhappy ministers and political opportunism as departments such as those in the tourism sector see their budgets cut to fund the COVID-19 response. We anticipate that the finance minister will reiterate Treasury’s commitment towards managing down the wage bill as a proportion of total expenditure – we can no longer afford government vanity projects and largesse.

The finance minister also knows that he needs to show that SA’s debt is slowly coming under control so we should look forward to some aggressive inflation assumptions and also some aggressive economic growth numbers to mean that we project SA’s national debt as a percentage of GDP to plateau in 2024.

We do not think that inflation will be much above 3% in the near term or great deal higher than 4% in the longer term. This does make the minister’s job more difficult and the only viable route for Mboweni is to announce an economic growth plan. Dusting off the rhetoric of the National Development Plan (NDP) will not be enough. Government investing in infrastructure through corrupt tender processes will be met with disbelief after years of failed attempts and theft. State capacity to invest in, and manage, projects has been hollowed out over the past decade and, absent a partnership with the private sector, this does not provide a believable avenue for growth. Similarly, it is difficult to see how another state-owned bank does much for the country’s growth prospects beyond raising even more government debt.

In short, we need to hear how government is going to work with the private sector to reignite growth and job creation. The private sector has, for the most part, a disastrous track record of investing abroad. We need to see government partner with the private sector to unlock this investment for SA rather than see it squandered in Europe and Australia. Government should provide stable and sensible regulations, allowing the private sector to provide capital and technical skills. The extent to which the minister is able to announce a movement in this direction will determine how the market reacts to his budget.

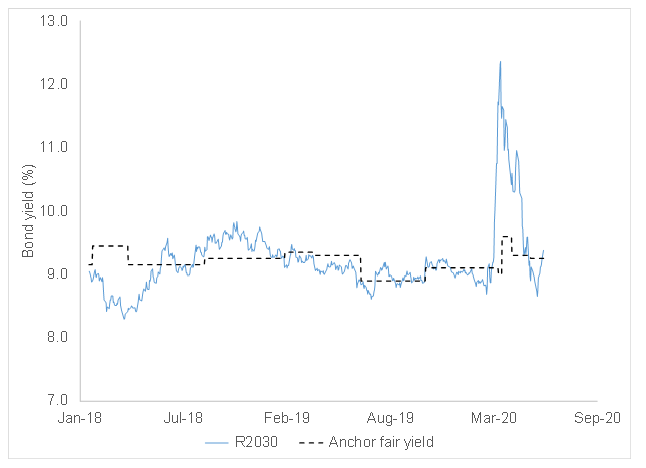

Global risk appetite has been dampened by the possibility of a second wave of COVID-19 infections in China. As a result, we have seen the rand give up some of its recent gains, while the SA 10-year bond has also weakened. We are maintaining our view that the rand will, over time, recover more ground and that the fair yield for the SA 10-year bond is around 9.25%. This means that we think bonds are fairly priced for the risks in the system and that the rand stands to benefit when global risk appetite returns. However, in the short term, the extent to which the finance minister announces meaningful, believable plans to allow our economy to grow will determine the behaviour of both these asset classes. Bond yields will be the yardstick against which we can measure both his performance and SA’s prospects as a country.

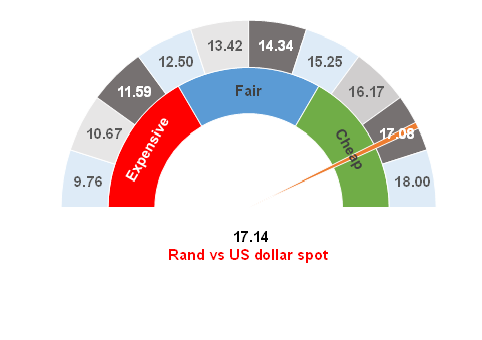

Rand

The rand is currently trading at around R17.14/$1. In the near term it is all about the budget on 24 June. However, longer term, we maintain our view that the rand should recover more of the lost ground. We think that, in the context of the risk in SA, a fair value for the rand is between R15.00 and R16.00/$1.

Figure 1: Rand vs US dollar

Source: Anchor

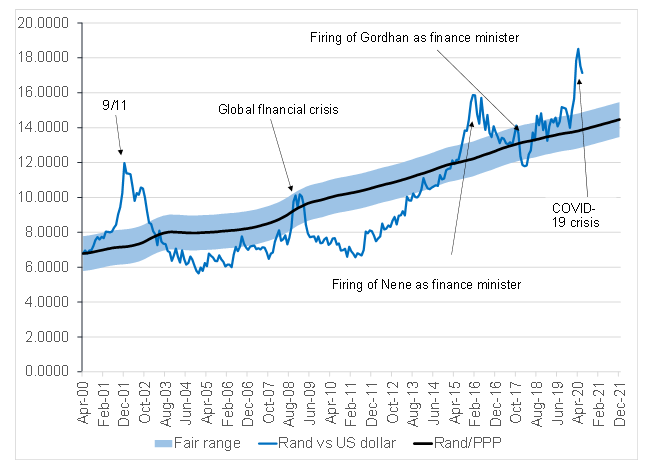

Figure 2: Actual rand/$ vs rand PPP model

Source: Anchor

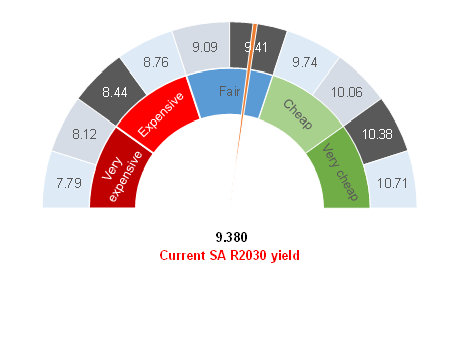

Bonds

The SA 10-year bond is offering an interest yield of around 9.38%. This is just above our fair yield and well within the fair range. We think that this yield adequately compensates for the risk of holding 10-year SA debt. A sensible growth budget will see this yield decline.

Figure 3: SA R2030 (2030 maturity) vs Anchor fair value

Source: Anchor

Figure 4: Anchor SA bond yield monitoring – R2030 bond

Source: Anchor