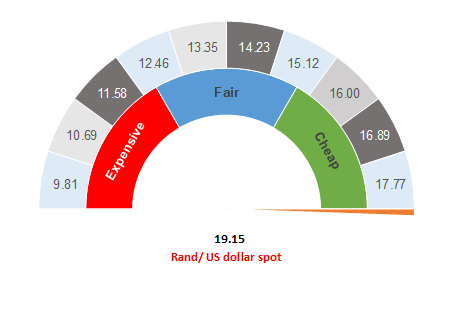

Figure 1: Rand vs US dollar

Source: Anchor

Sentiment towards emerging markets (EMs) have turned very negative and, as a result, EM currencies have come under pressure. On Monday (6 April), the rand reached a new all-time low of R19.35/$1, with the local currency currently caught up in a tsunami of global events. The poor US jobs numbers sparked a risk-off sentiment towards EMs last week, with all EMs caught in the sell-off but South Africa (SA) even more so, suffering as it does from some self-inflicted problems. SA’s poor fiscal position, excessive debt burden, and recent downgrades by Moody’s and Fitch (with a likely S&P downgrade soon) as well as our impending expulsion from the World Government Bond Index (WGBI) all mean that, in a weak economic environment, SA will be punished and, consequently, the rand has weakened more than most EM currencies.

It was also reported on Monday that the ANC-led tripartite alliance, which includes the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the SA Communist Party (SACP), have written a letter to President Cyril Ramaphosa suggesting that the SA Reserve Bank (SARB) should rather print money (as a developmental mandate) or borrow from alternate sources (China, the SARB or prescribed assets [pensions]), instead of allowing National Treasury to approach the IMF. This makes no sense to us since all financial market participants have been clear that SA’s major problem is the country having too much debt. More debt does not deal with the fundamental problem of excessive government debt and, to the extent it is implemented without structural reforms, we expect the rand’s depreciation against the greenback could then accelerate as domestic issues come to the fore. So, much depends on how government chooses to navigate these difficult times. A major consequence of COVID-19 on SA is that our fiscal highway has been shortened and difficult decisions are becoming immediate as our debt burden rapidly becomes unsustainable.

SA has a positive balance of trade at the moment and a weaker rand does help with our exports. Our main import is oil (for transport) and, fortunately, the current low oil price is keeping the rand-denominated fuel cost down. We expect that the oil price will recover towards $55/bbl in due course, which will create a significant inflationary effect for SA and will stifle our economy. We have benefitted from recent interest rate cuts but could see these benefits reversed should oil recover at a time when the rand is weak. The reality is that every imported good that we consume has effectively become 35% more expensive and the weaker rand is another symptom of investors losing confidence in the country.

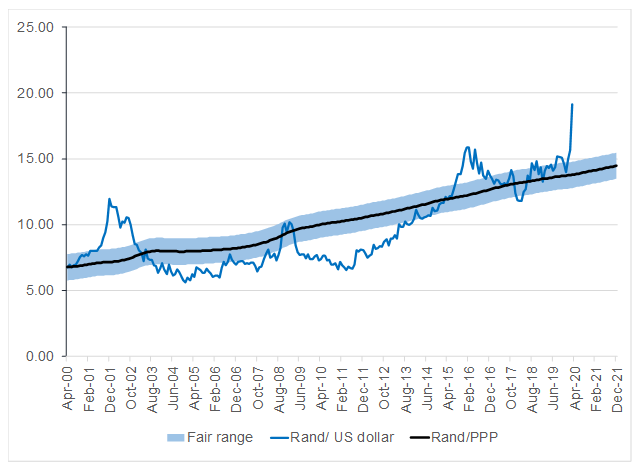

Unfortunately, while not our base-case scenario, we are also currently still in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis and, in this environment, the rand could weaken to new record lows beyond what we have already seen. Nevertheless, we still think that, over the coming months, the COVID-19 crisis will pass, thus allowing the local unit to stage a recovery towards our fair value level of c. R15/$1. However, as highlighted, the rand’s fortunes are closely tied to global sentiment at present, which can be extremely fickle. On Tuesday (7 April), market sentiment was more positive towards EMs and the local currency is recovering slightly. We have been gradually repatriating foreign investments to reduce our exposure to the US dollar at current levels.

Figure 2: Actual rand/$ vs rand PPP model

Source: Bloomberg, Anchor