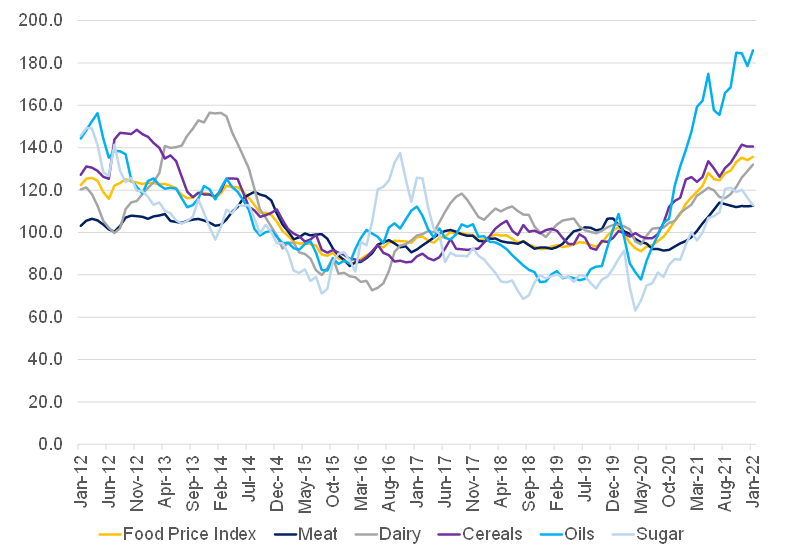

As we move into February 2022, inflation once again remains a dominant theme, particularly in the larger developed countries, where inflation has risen to multi-decade highs. The continued heightened inflation in many parts of the world has largely been driven by a combination of supply chain disruptions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken to manage its impact, as well as weather conditions in key production regions and structural drivers of demand. Naturally, this has become a cause for concern for economic policy makers and financial markets alike, and the role that food prices play in this current environment has not gone unnoticed. As illustrated by the FAO Global Food Price Index (a measure of the monthly change in the international prices of a basket of food commodities) in Figure 1 below, global food prices for key food categories have been rising noticeably since mid-2020.

Figure1: FAO’s Global Food Price Index performance

Source: FAO, Anchor

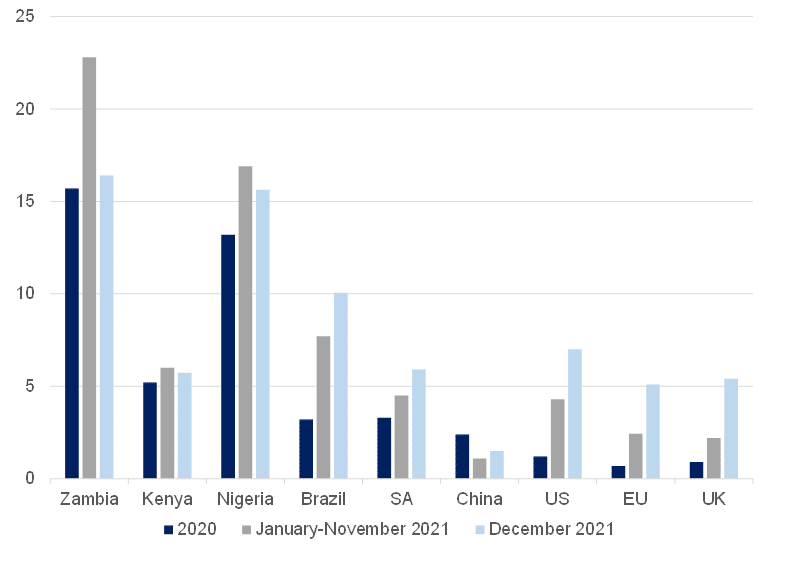

If one considers South Africa (SA) in particular, domestic agricultural commodity prices have primarily been underpinned by global prices over the past two years. SA, as a relatively small player in global agriculture, is consequently linked to the global market. Thus, when considering key price drivers in SA, typically the size of the domestic harvest matters less than the crop conditions in South America or grains and oilseeds demand in China and India, etc. Consequently, the general rise in global prices overshadowed the improved domestic crop supply in the 2020/2021 production season. Nonetheless, as indicated by Figure 2 below, SA food price inflation has tended to be lower than in at least one of our BRICS partners (Brazil), in the US and in some other African countries, but notably higher than in China and the EU.

Figure 2: International food inflation comparison, YoY % change

Source: IMF, Anchor

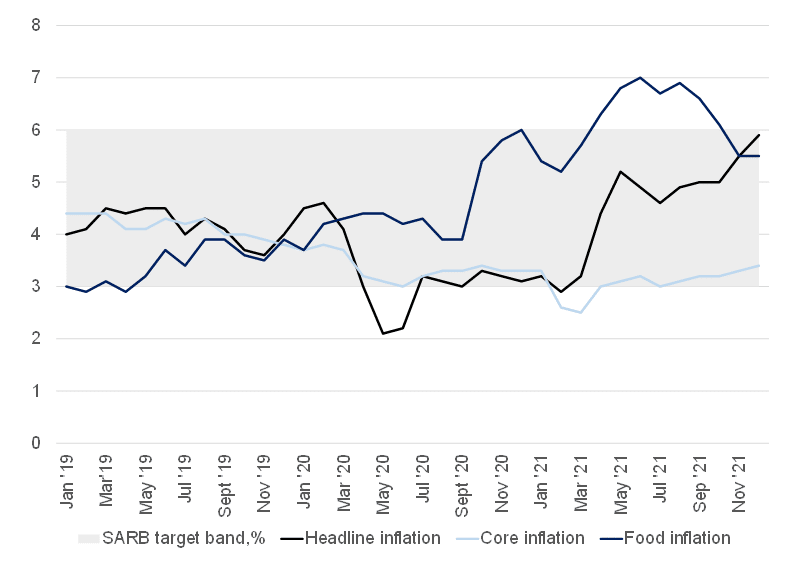

The latest round of disruptions relating to the spread of the Omicron variant, combined with excessive rainfall in the summer rainfall areas globally, has presented the possibility of further supply disruptions that could, in turn, affect global and local inflation. International meat and other food prices lost some momentum in early December, but firming demand has since driven prices firmer. Locally, the high December rainfall in both the eastern and western parts of SA’s summer crop production areas is likely to result in a smaller grain and oilseed harvest compared to the past two seasons. However, stocks from previous bumper crops are likely to prevent considerable local price increases. SA food inflation data for December 2021 printed at 5.5% YoY, down notably from a peak of 6.9% YoY in August 2021. The main contributors to the persistent local food inflation remain oils and fats (+20.8% YoY), meat (+8.6% YoY), and dairy and eggs (+5.3% YoY).

Figure 3: SA inflation, YoY % change

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

Overall, underlying agricultural commodity prices remain firm. With respect to meat prices, ongoing tight supplies, combined with strong festive season demand resulted in monthly meat inflation of 1.2% for December. Poultry prices also firmed towards the end of 2021 largely as a result of higher input costs. International factors continue to dominate price dynamics in vegetable oil markets. In 2021, the prices of oilseeds surged due to production disruptions and long-term structural changes in the palm oil market, further exacerbated by increased demand for oilseeds as feedstocks for biofuels. These dynamics have persisted in the last weeks of 2021, but recent developments such as flooding in Malaysia (the world’s second-largest palm producer) and dry conditions in South America, have fuelled new upward momentum in vegetable oil markets.

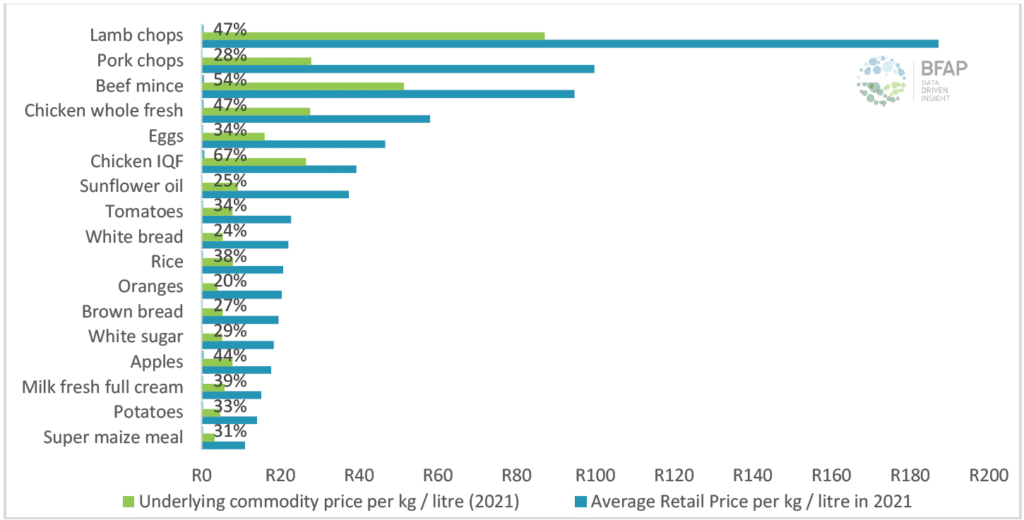

Aside from firmer underlying agricultural commodity prices, costs along the value chain have also contributed to food inflation. Figure 4 below from the Bureau of Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) presents a few representative examples of average price (of the underlying commodity) vs final retail products. The share of commodities in the price of final retail products ranges from as low as 20% to 67%, indicating that additional cost factors in the value chain, such as logistics, processing, and value addition, also make a significant contribution to food inflation. It is important to note that pandemic-related disruptions have further added to these costs, while prices of factors such as fuel and electricity have increased greatly over the course of 2021. In December 2021, the YoY inflation rate for administered prices was 15.6%, while SA inflation on electricity and fuel measured at 14% and 40.5%, respectively.

Figure 4: Share of underlying commodity prices in final retail value in 2021

Source: BFAP

So, the questions remain, should we be worried about food inflationary pressures and what can we expect in 2022? We forecast that global food inflation will moderate over the coming months because of high base effects associated with high price levels during 2021. There is, however, notable upside risk to this view. Global climatic conditions remain a key factor, particularly with regards to South America. Persistent dry conditions in South America would be a key price driver in global grain and oilseed markets. Based on the significant expenditure share of bread and cereals in the SA consumer’s expenditure basket, this could play a key role in inflationary figures over the coming months.

Another key determinant that drives upside risk is energy prices. Crude oil prices remain upwardly sticky, with many idiosyncratic factors at play. Oil prices have started the year stronger than previously forecast as supply remained constrained – not only has OPEC+ been slow to ramp up production, but some OPEC members have also experienced specific production disruptions. Simultaneously, demand has remained firm during the Northern Hemisphere winter, while transport sectors globally have seen a further improvement in activity. Global oil inventories also remain comparatively low.

Should the oil price rise further, it would simply add to the broad-based increase in food production and manufacturing cost, which could, in turn, push prices higher. Nonetheless, we still believe that, on balance, food inflation will moderate over the coming months as a result of high base effects associated with high price levels during 2021. Concurrently, SA headline consumer inflation should temporarily spike towards the SA Reserve Bank’s target ceiling, boosted by higher food and fuel prices. This ultimately creates strong favourable base effects that support the moderation that we foresee in 2H22, despite the gradual rise anticipated in underlying inflation. This, along with generally weak demand-pull or second-round inflation pressure, should underpin a gradual interest rate normalisation path, in our view.