The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has brought significant uncertainty to global trade, largely due to disruptions in supply chains and weakening demand. This is particularly notable within agricultural trade, as several countries across the globe have adopted restrictive trade policy approaches (such as export quotas or outright bans) since the start of the pandemic. The justification for these policies was consumer-focused, as countries needed to ensure domestic food security during the pandemic. Fortunately, after data released by the International Grains Council indicated that there are ample global grain supplies in 2019/2020 and prospects for a larger crop in the 2020/2021 production season, countries such as Russia, Cambodia and Vietnam (amongst others) reversed their protectionist policies. However, on the African continent, unfortunately, we continue to witness these restrictive trade practices, which are producer-focused instead of consumer-focused, as has been the case on other continents.

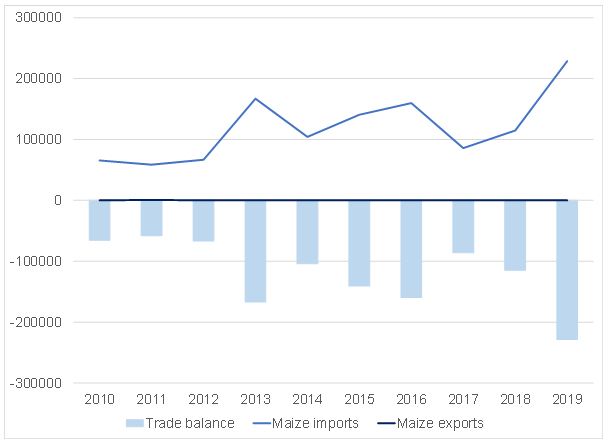

One of South Africa’s (SA’s) closest agricultural trading partners, neighbouring Namibia, is one such example. As of 1 June 2020, the Namibian Agronomic Board (NAB) has suspended imports of maize and millet, until the domestic harvest has been absorbed by local millers. Namibian authorities expect the ban to be in place at least until November 2020. The rationale provided is that this policy will ensure that domestic farmers have a market for their produce, which will support them during the pandemic. However, if one takes a closer look at the Namibian maize market, this restrictive trade policy is simply not practical. Maize is one of the major staple crops in the country, although largely dependent on imports. Over the past five seasons, Namibia’s maize production averaged 59,000 tonnes, a small fraction of their average annual maize consumption needs of 216,000 tonnes. Thus, the difference is usually imported, which now notably NAB has temporarily stopped. Such a policy is heavily producer orientated, at the expense of consumers that could benefit from competitively priced imports.

Figure 1: Namibia’s maize trade, in tonnes

Source: ITC Trade Map, Anchor

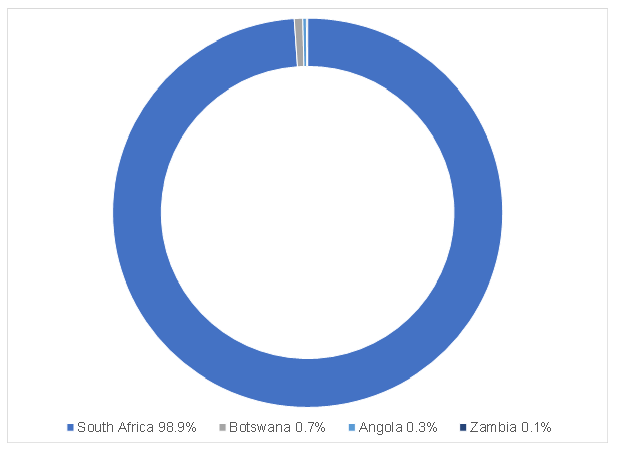

Figure 2: Namibia’s maize import markets, 2019

Source: ITC Trade Map, Anchor

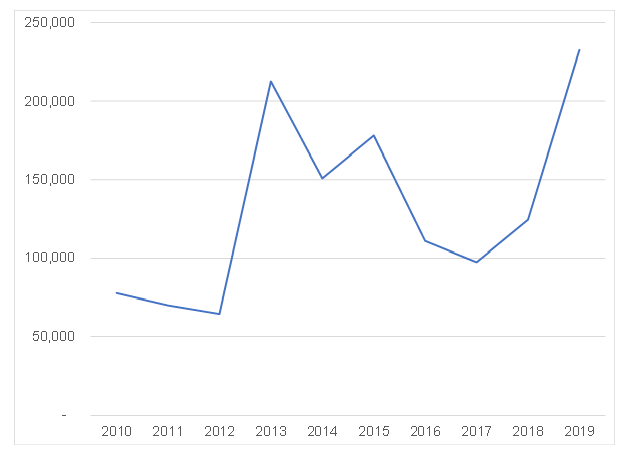

As Namibia needs to import c. 72% of its annual maize consumption, placing a temporary ban on these imports is not a viable or credible policy option, in our view, particularly during a global pandemic when governments ought to be sourcing the most affordable food for its citizens. Furthermore, in the absence of trade barriers, said affordable food will be close at hand this year. SA, Namibia’s main maize supplier, is expecting its second-biggest maize harvest on record – around 15.2mn tonnes, according to the latest data from the Crop Estimates Committee. Consequently, the forecast bumper crop will likely push maize prices downwards, below the current average of R2,600/tonne that both white and yellow maize are drifting around. Naturally, such price declines would be beneficial to Namibian consumers. The Agricultural Business Chamber of SA (Agbiz) currently estimates that SA could have about 2.7mn tonnes of maize for the export market – up 90% YoY.

Figure 3: SA maize exports to Namibia, in tonnes

Source: ITC Trade Map, Anchor

The Namibian government’s attempt to provide support to local farmers through trade policy will likely have very little success. There is no certainty that Namibia’s domestic maize harvest will be of acceptable quality to attract millers. Furthermore, Namibia has not been self-sufficient in maize production for over two decades. Such policy mismatch and uncertainty does little to help an economy that was already struggling through a recession pre-COVID-19.

Taking a broader look across the continent, Namibia is one of many countries across Africa where the ongoing COVID-19 crisis has brought significant uncertainty to agricultural trade. McKinsey & Company estimates that the pandemic could cost Africa $4.8bn in lost agricultural exports and affect the livelihoods of over 10mn farmers. These losses are likely to emerge from COVID-19-related disruptions, such as cancelled flights and the closure of chocolate factories in Europe, which have limited exports of crops such as nuts and roses, whilst livelihoods would be lost through job cuts and reduced prices. McKinsey further forecasts losses of between $500mn and $2bn in exports of fruits, vegetables, and nuts. In addition, a decline in the demand for chocolate and the consequent drop in prices could reduce cocoa exports by as much as $2bn. Exports of coffee, which supports about 6.6mn jobs mainly in East Africa, could decline by about $200mn. The loss of flower export revenues is estimated at $400mn-$600mn. This, coupled with the ongoing locust invasions, could also interrupt preparations for the next planting season.

In May, Tanzania’s agriculture ministry warned that the pandemic may impact food security and that containment measures adopted by several countries will have long-term implications for the global economy. In its National Security Bulletin, the ministry warned that ‘timely access to agriculture inputs for crop cultivation would be delayed by disrupted transport and markets, hence affecting yields and income’. The World Bank issued a similar warning at the end of May, highlighting that labour shortages are starting to impact producers, processors, traders, and trucking/logistics companies in food supply chains. It further noted that ensuring farmers have access to inputs and labour for the next planting season is a major concern.

However, compared to Namibia and other African counterparts, SA’s agricultural sector is leading the pack. In 1Q20, SA recorded an agricultural trade surplus of $773mn. This is 16% higher YoY, with exports having increased at a higher rate than imports. The export increase was underpinned by grapes, maize, wine, wool, pears, apples, plums, lemons, and macadamia nuts, among other agricultural products. These products are likely to underpin SA’s agricultural export basket in 2Q20 (which largely corresponds with global lockdowns), but notably with a decline in wine exports that were impacted by domestic lockdown regulations.

Whilst SA’s 2Q20 data will only be out in July, high-frequency data from various commodity organisations and agricultural institutions point to continued robust agricultural exports over the past few weeks. Along with the forecast bumper maize harvest, citrus will feature prominently in 2Q20 data onward, as this year’s exports are expected to reach a record 143.3mn cartons for the Southern Africa region, mainly from SA. Notably, the export activity of citrus continued with minimal interruptions during the lockdown period.

The African continent and Europe continue to form the largest markets for SA’s agricultural exports, accounting for a 44% and 29% market share, respectively, in terms of value during 1Q20. Thus, given the current weakness in the African continent’s agriculture sector, SA is presented with further trading opportunity within its largest agricultural export markets. Overall, while the pandemic will result in a loss of incomes (and in turn, a decline in the demand for goods), the agriculture and food sector look set to be one of the few sectors within SA to not be as hard hit. As such, for 2020, SA’s agricultural exports are forecast to increase to levels over $10bn from $9.9bn in 2019. The key catalysts for said growth will be the increase in grains and horticulture output, and the intrinsic advantage gained by weakness in the agricultural sectors of neighbouring countries such as Namibia and the rest of the African continent.