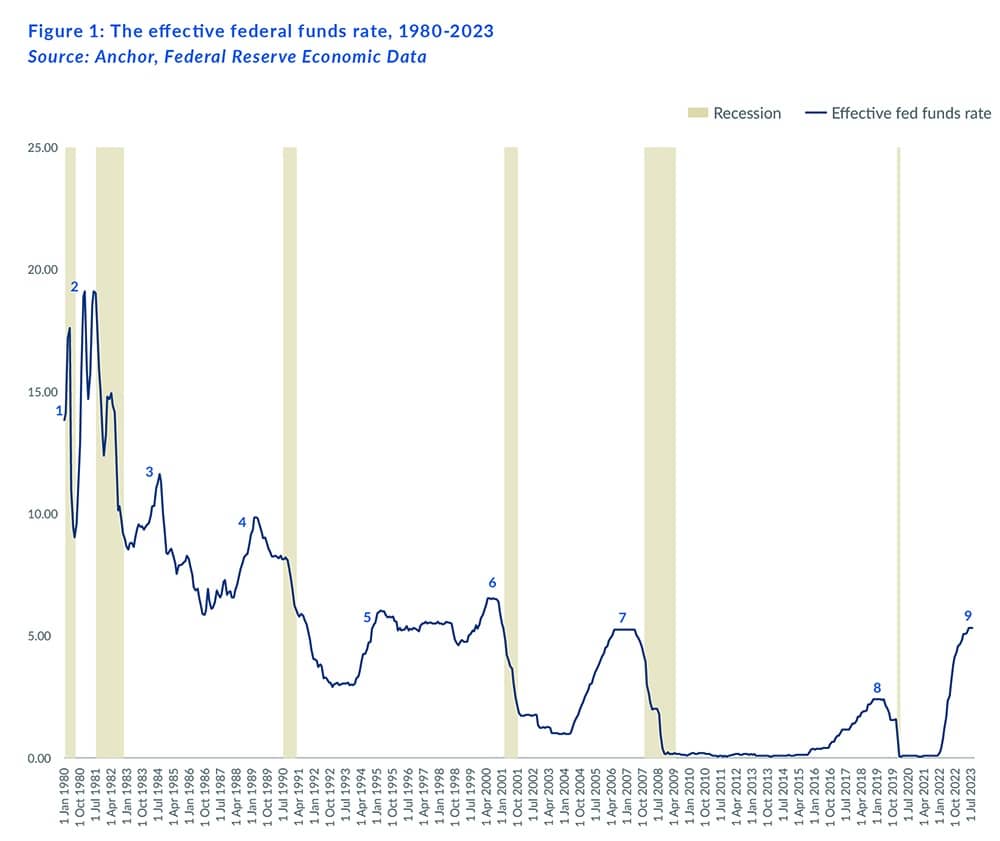

The US Fed is facing a difficult challenge – bringing inflation back to its 2% target without triggering a recession. This precarious balancing act is known as a soft landing. Soft landings are the holy grail of monetary policy. However, achieving this feat has historically proven challenging for the Fed. Since 1980, the Fed has embarked on eight monetary tightening cycles (excluding the current one), with the US economy tipping into a recession six times (see Figure 1). So far, the progress of the current tightening cycle has been relatively painless, as inflation has moderated while the labour market remains tight. This article explores why we believe recession risks remain high despite growing soft-landing optimism.

How does the Fed control inflation?

When the Fed is concerned about actual or developing inflation, it raises the interest rate in the federal funds market. This action subsequently increases other interest rates throughout the economy via financial arbitrage. Higher interest rates make credit more expensive and dampen aggregate demand, especially for houses and vehicles. Dampened aggregate demand reduces inflation. If the Fed raises the policy interest rate just enough to slow the economy and bring inflation down (closer to its 2% target) without causing a recession, it is known as a soft landing.

A classic example of a soft landing is the monetary tightening cycle conducted under former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan in the mid-1990s (see Figure 1). However, if the Fed raises the policy interest rate too much, it may cause a recession – this is known as a hard landing. An example of a hard landing is the monetary tightening cycle conducted under another former Fed Chair, Paul Volcker, in the early 1980s (see Figure 1).

The current monetary tightening cycle

Since 2022, the Fed has raised the fed funds target range to 5.25%-5.5%. The Fed’s current policies include unconventional monetary policy tools such as quantitative tightening (QT). So far, a recession has not occurred. US economic data has revealed a moderation in price pressures and a gradual cooling of the labour market – indicating a relatively painless progress in the Fed’s fight against inflation. This has fuelled optimism for a soft landing, with many investors rethinking the narrative of higher interest rates persisting for an extended period. Indeed, the US economy has shown surprising resilience thus far. However, we remain attuned to the following recessionary risks.

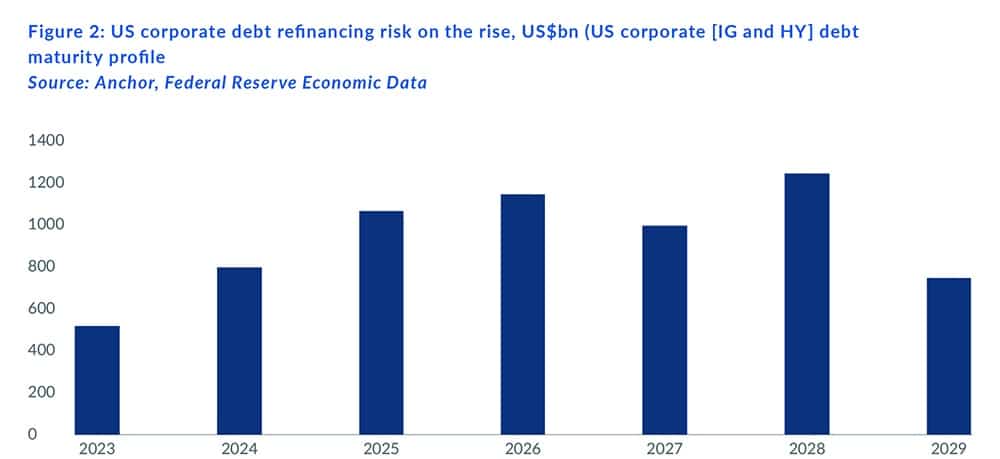

The pace of US corporate debt (investment-grade [IG] and high-yield [HY]) maturing picks up sharply from 2024 onwards, following muted refinancing needs due to the cheap debt raised in 2020 and 2021. US corporate debt maturities increase from US$500bn in 2023 to US$800bn, US$1.1trn, and US$1.15trn in 2024, 2025, and 2026, respectively (see Figure 2)

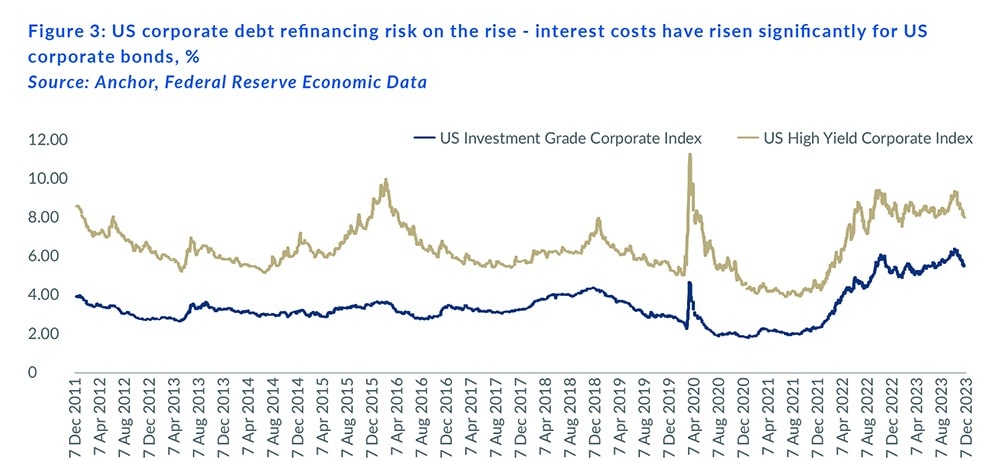

The Fed’s tightening cycle has increased corporate funding costs over the past few years. To provide context, US IG corporate borrowing rates are now three times higher than those seen in 2020-2021 and nearly double the rates witnessed between 2012 and 2019 (see Figure 3). Similarly, the US HY corporate borrowing rates have doubled compared to the 2020-2021 levels (see Figure 3).

Corporates typically refinance debt obligations several months in advance. This means that US corporates aiming to refinance upcoming debt obligations today will continue encountering at least twice as high funding costs due to elevated interest rates. As these substantial debt maturities approach, US corporates will confront challenging decisions. They must choose between reducing their debt levels and scaling down their operations or implementing cost-saving measures, such as job cuts, to facilitate refinancing at double the cost, maintaining their sustainability.

The combination of tighter financial conditions stemming from increased funding costs, rising operating expenses due to inflationary pressures, and the substantial rise in refinancing requirements due to significant debt maturities will hasten the softening of the labour market, accelerate the pace of corporate defaults and cause a harder slowdown in economic activity. A similar situation is also observed in Europe.

The presence of external shocks complicates landings

Steering the economy toward a soft landing is a delicate task that can be easily disrupted by external shocks—shocks beyond the scope of monetary policy. Examples of such shocks include supply and fiscal shocks. Central banks, including the Fed, have various conventional and unconventional monetary policy tools to fight or stimulate inflation. However, these tools primarily target aggregate demand, leaving the Fed with very little control over aggregate supply.

Historically, adverse supply shocks, such as oil and food shocks, have complicated the mission of achieving a soft landing, often leading to severe recessions. A prime example is the Fed’s tightening cycle from 1972 to 1974, which was significantly affected by two adverse supply shocks (oil and food) and the end of price controls. Another instance is the Fed’s late 1980s and early 1990s endeavour, which faced negative impacts from adverse supply shocks (particularly oil shocks) triggered by Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

Fiscal shocks have also historically caused turbulence in achieving a soft landing. An example is the Fed’s modest tightening cycle from 1965 to 1966. The Fed embarked on a tightening cycle because it was worried that the overheating economy (caused by the increased defence spending for the Vietnam War in the mid-1960s) may be inflationary. These worries proved to be well-founded.

External shocks, such as supply and fiscal shocks, have impacted the current tightening cycle. These external shocks are:

- COVID-19-induced global supply disruptions.

- Oil shock.

- Food shock.

- COVID-19-induced fiscal stimulus.

All four external shocks in the current cycle are inflationary, making it more challenging for the Fed to rein in inflation. This means that the Fed becomes forced to keep interest rates higher for longer as it fights against stubbornly high inflation. The longer the interest rate stays elevated, the harder the economic slowdown.

Long and variable lags in monetary policy create a human danger.

Monetary actions, such as changes to the policy interest rate, take time to impact various elements of the real economy, like inflation, employment, and economic growth – a phenomenon known as the long lags. The lags are also variable as the time between cause and effect can differ for each element and tighten the cycle in a nearly impossible way to predict. Moreover, external shocks can extend these lags, creating a real human danger as policymakers might witness minimal or no immediate effect in reducing inflation due to these additional inflationary pressures. Consequently, they may continue raising interest rates beyond what is necessary to reduce inflation, potentially leading to a hard landing. All else equal, altering interest rates until its full effects on the real economy can take a year or two. Despite the tightening nearing the two-year mark, many believe that the full impact of the current tightening is still working its way through the real economy, given the continued strength of the labour market and growth acceleration.

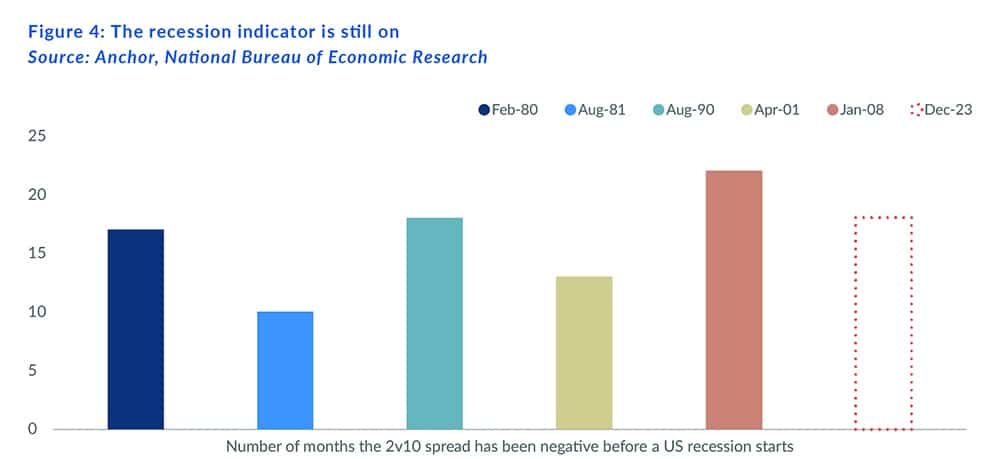

Bond markets, by nature, are forward-looking – prices reflect what investors think will happen to the economy in the future. The bond market is still calling a recession, albeit with a lower probability than 12 months ago. Historical data suggest that yield curve inversion often precedes a recession – it is considered a key recession indicator. When the 2v10 spread (the difference between the yield on the 10-year US bond and the yield on the 2-year US bond) turns negative, the yield curve is considered inverted. Since the late 1970s, an inverted US yield curve has been able to anticipate five of the six recessions. Figure 4 shows the number of months the 2v10 spread was negative before a US recession started in 1980. The average number of months is 16 – a recession generally hits the US economy 16 months after the US yield curve inverts. After more than 500 bps of Fed hikes, today’s US yield curve has been inverted for about 18 months, well within historical standards.