I covered the SA-listed diversified miners on the sell-side (the term used in the financial services industry that denotes a firm that sells investment services to asset management companies [buy-side] or corporate entities) for over two decades – starting in 1994. In this article, I give my perspectives on how investors should think about investing in mining shares. Mining shares are volatile and somewhat unpredictable compared to many other sectors. Covering the miners can be humbling at times. Even seasoned mining analysts periodically make fools of themselves. However, covering the miners teaches you that nothing goes up forever. You get regularly reminded of how quickly things can change. The miners are also a solid valuation grounding school.

Even though I covered mining stocks professionally, my personal investing journey has always stretched far beyond the mining sector. My investments have been global and local, mainly outside the mining sector. These days, I cover global equities for Anchor. I would describe myself as an investment enthusiast who just happened to cover the mining sector. Had any other sector fallen in my lap in 1994, I would probably have enjoyed covering it just as much as the miners.

It has often been said of the miners that “you do not buy them, you rent them”. The volatility and unpredictability of mining stocks mean you quickly take the profits that the sector offers you. At Anchor, we consider ourselves to be ‘quality-growth’ investors. For the most part, the miners do not fit into this camp. It is much harder to find secular compounders in the mining sector like you sometimes find in the global tech sector, for example.

As a quality-growth fund manager, you typically try to buy asset-light, high-margin, and high return-on-capital-employed (ROCE) assets. The miners struggle to fit into this investment style. Mining companies are capital-intensive with a finite resource base. These companies also often have a low ROCE on a through-the-cycle basis.

Let us take a theoretical example of a retailer that owns 100 stores when you invest in it. When you buy the share, the retailer plans to close five stores every year for the next 20 years, meaning that in 20 years, the retailer will close its doors and cease to exist. Essentially, you sign up for this when you buy a miner – it is a finite and ever-depleting resource. While this oversimplifies the reality of investing in mining shares, I think my point is made.

When mining companies start mining a new deposit, it stands to reason that they will attempt to mine the best parts first. As the years roll by, grades fall, and haulage distances increase, especially with underground mines. Therefore, costs steadily rise. Some mining companies spend significant amounts of money on so-called ‘expansion capex’ over many years without growing their overall production volumes. In other words, what they define as volume expansion, is just replacement volumes to offset the otherwise declining production base.

There can sometimes be a sting in the tail of the bull thesis for a specific commodity. On occasion, the bull case for a commodity price is based on rising producer costs, falling industry production and a lack of discoveries. Remember that when you buy a commodity producer, you might be investing in some of the cost and production challenges yourself. It is often not a free lunch when you buy shares in the underlying commodity producers.

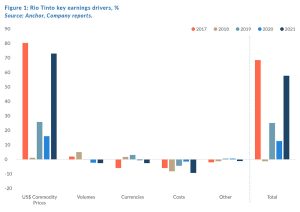

There are four key drivers of the US dollar earnings of a commodity producer – US dollar commodity prices, production volumes, producer currencies and production costs (in local currency terms).

Figure 1 below summarises the drivers of Rio Tinto’s US dollar earnings over the past five years. The chart below shows the percentage impact of each driver on Rio Tinto’s US dollar earnings; all other factors held constant. The individual drivers add to the totals on the right-hand side of the chart each year.

In my experience, US dollar commodity prices are unequivocally the key earnings driver for miners. So much broker research is written about the other three drivers, and while this can add interesting angles to the investment thesis, it always comes back to the move in US dollar commodity prices. This is a simple reality.

Production volumes are typically the smallest of the four earnings drivers in any given period. This is especially true for large, established, diversified miners. The make or break of any earnings report is unlikely to come from the production volume numbers unless you are dealing with a smaller startup.

The move in producer currencies can appear to be a reasonable driver at face value. However, here the catch is that those producer currencies (such as the SA rand or the Australian dollar) are often driven by moves in US dollar commodity prices. These two drivers should not be viewed independently of each other. While SA miners are supposed to benefit from a weaker rand, ironically, some of the best share price performances can occur when the rand is strengthening in response to rising US dollar commodity prices.

The change in local currency-based operating costs (away from the move in producer currencies) is what we should evaluate mining management for above anything else. For the most part, this is all mining management has under its direct control. Compared to many other sectors, it always feels that mining management has so little it can directly influence.

The miners cannot change production volumes in the same way that an industrial or tech company can. A software company can sell an almost unlimited amount of its products. The miners cannot run sales promotions or launch exciting new products. The miners cannot innovate or decide to raise prices by 10% of their own accord because input costs have risen.

For the most part, mining management is about controlling costs. One key to controlling costs is ensuring that the miner invests in the correct assets. In the long term, it is almost always true that controlling costs in an open-pit mine is easier than in a deep-level, hard-rock underground mine. Rio Tinto and BHP (arguably the world’s two leading diversified mining companies) have long curbed their exposure to deep-level, underground mining for this reason. Here the argument goes that no one can control costs in a miner if you are in the wrong assets.

Notwithstanding my cautious approach to the miners, there are times in history when the miners have offered investors outlandish returns. If you could catch one of these in your investing journey at some point in the future, you would be well rewarded. Three times in my career, the miners have offered returns asymmetrically skewed to the upside. These periods were around 1998, 2009 and 2015.

There is one other unique investment opportunity that the miners offer periodically. High net debt is a hurdle that non-cyclical companies struggle to overcome. For example, it is very hard for a consumer business to trade its way out of a debt crisis. It is not as though the company can temporarily double its selling prices while it pays down its debt. Often, these companies do not survive or have to conduct deeply dilutive rights issues. This locks in a permanent capital loss for the company’s equity shareholders.

However, the debt crisis for a miner is often triggered by a temporary collapse in its underlying commodity prices. Provided the miner can hang on long enough without triggering a rights issue, the inevitable recovery in commodity prices can enable the miner to manage its debt down via rising operating cash flows. In 2015, Anglo American and Kumba Iron Ore were excellent examples of this. These high net-debt, low equity value situations can easily present ten-bagger opportunities. I would summarise my view as follows: It seldom makes sense to buy a company overwhelmed by debt, but if you do, your best chance of success is with a cyclical commodity-type company.

A final issue I would highlight is that there is arguably a difference in how global and local fund managers think about investing in the miners. Materials (excluding energy) account for only about 3% of the S&P 500 Index. Most global fund managers can largely ignore investing in the miners because of their comparatively small size and the unpredictability of the sector. Once every few years, a global fund manager might put a small percentage of their fund into a couple of mining shares when the investment opportunity is asymmetrically skewed to the upside. If it works, they add a few percentage points to their returns. If not, then very little performance is lost.

However, SA captive money does not have the luxury of ignoring the miners. The mining sector accounts for c. 25% of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index. It is too big a weighting to ignore. Also, there has been a material reduction in the number of companies listed on the JSE over the past two decades. As such, the range of investment opportunities on the JSE has shrunk.

In as much as I have suggested that the miners are not in the global quality growth camp, within the mining industry, some truly world-class mining companies are listed on the JSE. BHP, Glencore and Anglo American are all arguably within the top 5 diversified miners in the world. That makes the JSE-listed miners unique relative to the local banks and industrial companies. Furthermore, a company like BHP has no assets in SA, so it offers local fund managers some geographic asset diversification outside of SA.

Mining companies struggle for space within a global portfolio. However, in a local portfolio, they are well worth their place. Nevertheless, the current point in time does not feel like a unique buying opportunity for these miners. The upside and downside risks seem about evenly balanced. It, therefore, seems like a stock picker’s market, searching for individual mispricing opportunities.