The market was left stunned as the Magnificent Seven or Big 7 tech giants (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Tesla) reported results recently and outlined capex plans, projecting 40%-plus increases in their investment budgets for 2026. Instead of being applauded, many of these announcements were met with sharp share price declines, as investors expressed scepticism about whether incremental profits would be sufficient to justify the eye-watering investments.

Demand for computing capacity is undeniably growing at an unprecedented pace. The Big 7 are expected to spend c. US$650bn on AI-related infrastructure in 2026 alone (including on data centres, chips, energy, etc.), on top of an already extraordinary US$450bn spent in 2025. To put that in context, it is like building 100 nuclear power plants, more than South Africa’s (SA) GDP (US$500bn), almost as much as the US’ annual defence spend and as much as rebuilding the entire US Interstate Highway System (a c. 78,600 km network of freeways connecting US cities) in a single year, but in silicon.

Despite the urgency to invest, monetisation remains uncertain. These companies are racing to build capacity because falling behind could be an existential threat – but this does not guarantee attractive returns. The key question investors must now confront is simple: Is this AI capex boom value-creating, or are we entering a late-stage investment cycle where capital is deployed faster than profits can follow?

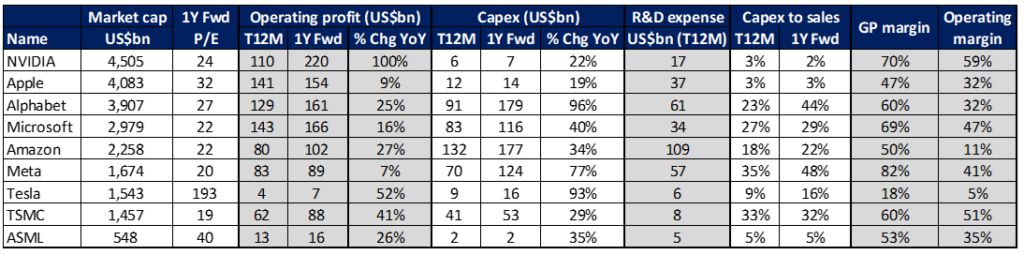

Figure 1: The profits and spending of the big tech companies

Source: Anchor Capital, Bloomberg

There are some fascinating takeaways from the table in Figure 1 above:

- The big spend is primarily from four companies who are building computing capacity – Amazon (US$148bn), Alphabet (US$132bn), Meta (US$123bn) and Microsoft (US$116bn).

- The valuation of most of the shares mentioned above is around a forward 20x-23x P/E multiple, which is roughly the same as the market average. These companies are not relatively expensive and do not appear to be in the much-publicised “bubble”. Apple (31x) and Alphabet (28x) are the expensive ones.

- Apple and NVIDIA stand out as having almost insignificant capex compared to the others. Apple clearly chose not to participate in this race for computing space. Its strategy currently looks clever – stand back and rent what it wants from the big spenders. Apple has just concluded such a deal with Google (Alphabet). Not surprisingly, its share price went up while all the others went down during the week of 1 February 2026.

- A lot of this spending is heading the way of NVIDIA (with an over 90% market share in high-speed graphics processing units [GPUs]). Still, NVIDIA itself ironically has minimal capex spend. Most of its production is handled by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which shows US$52bn of capex above. It is no surprise that NVIDIA is now the biggest and second most profitable company in the world (behind Saudi Aramco).

- The two biggest relative spenders are Meta (US$180bn capex and research and development [R&D]) and Amazon (US$223bn). Meta’s projected operating profit for 2026 is US$89bn, and it already has a massive advertising market share – it is difficult to picture where the incremental profit will come from to balance that profit and spend. Meta certainly cannot afford to continue spending at that rate unless revenue increases massively. The numbers seem to indicate that it is betting the house!

For most of the past 18 months, the market treated large AI capex announcements as a bullish signal. If management said, “We’re spending aggressively,” the share price often rallied. The logic was clear: demand is exploding, AI is transformational, and the winners will be the firms that build the most compute capacity the fastest.

But the market is now beginning to treat capex differently. Instead of applauding every major spend programme, investors are increasingly asking a more uncomfortable question: Will these companies actually earn an adequate return on the capital they are deploying?

And, if we zoom out, the ballpark estimate is that between 2025 and 2028, the “Big 7” technology companies could spend in the region of US$3trn on capex.

This is a number so large that it begins to distort the normal way investors think about corporate investment cycles. It is effectively the creation of a new global industrial complex — except this one is made up of GPUs, power grids, data centres, networking chips, and inference clusters.

What makes this moment different from prior tech cycles is that demand appears real, immediate, and accelerating.

Across the board, management teams are delivering a consistent message:

- AI demand is stronger than expected.

- Customer adoption of AI is faster than forecast.

- Computing supply remains constrained.

- The market is far from saturation.

In other words, the world is embracing AI faster than even optimistic forecasts predicted.

And the evidence is not just narrative. NVIDIA’s forward operating profit is expected to rise from US$110bn (T12M) to US$219bn, nearly doubling (+99%), while maintaining a remarkable 59% operating margin and 70% gross margin. That level of profitability is only possible in the presence of extreme demand pressure and strong pricing power.

However, the critical shift is that the market is no longer rewarding capex on faith alone. It is starting to penalise capex where the payoff is unclear, marking a shift from enthusiasm-driven pricing to return-driven scrutiny.

This is the classic late-stage investment cycle question: Are we building productive assets — or overbuilding capacity?

The return hurdle is massive.

If the Big 7 spend US$3trn on capex from 2025–2028, then even a reasonable 15% return on that capital would imply roughly US$450bn of additional annual operating profit.

That number is extraordinary. For context, the combined operating profits of these companies today are already roughly US$500bn–US$600bn.

In other words, the market is implicitly assuming that AI capex could potentially drive a world where operating profits double over the next 3–4 years.

That is a breathtaking assumption, and this is where scepticism becomes rational.

These firms already dominate many of the most profitable markets on earth: digital advertising, cloud computing, operating systems, mobile ecosystems, enterprise software, and e-commerce logistics.

The question is not whether AI will grow — it will.

The question is whether AI will create new pools of profit large enough to justify this magnitude of investment, without compressing returns through competition and commoditisation.

History is mixed. The internet created massive value, but it also created overinvestment (think telecom fibre buildouts). Cloud computing generated huge profit pools, but only a few firms captured them.

AI may follow the same path: enormous transformation, but profits concentrated in fewer hands than the spending suggests.

What does this mean for the shares?

The table in Figure 1 reveals clear differences in positioning.

- Apple is now the most expensive (a forward 31x P/E) and has reported excellent results after its iPhone 17 launch. This capex phenomenon has not negatively impacted it. Apple looks like a safe space to be, but its valuation seems too rich for such a massive company that we believe will battle to grow in double-digits over the longer term, even if it is just because of the law of diminishing returns.

- NVIDIA looks increasingly attractive, and its valuation is now just above the market average (forward 24x P/E). If AI demand remains tight, NVIDIA remains the tollgate and the share price has been flattish for around nine months, underperforming the market. Longer term, it is difficult to see how the current market share and margins (60% operating margin) are maintained. And as we point out above, the current spend cannot be maintained with massive revenue increases.

- Microsoft stands out as the best “quality compounder.” It combines scale with an exceptional 47% operating margin and forward operating profit growth of 16%, while still investing aggressively.

- Alphabet and Meta are the biggest capex swing factors. Alphabet’s capex rises 45%, Meta’s rises 77%, and both are pushing capex-to-sales sharply higher. The market is watching closely to see whether these investments translate into monetisable AI services.

- Amazon continues to invest heavily, but its 11% operating margin highlights that returns are still structurally lower than those of its peers.

The world is changing quickly, and AI demand is real. But the market is now asking a more mature question: AI capex is not automatically bullish — it is only bullish if returns follow.

For investors, the next phase of the AI trade will not be about who spends the most. It will be about who earns the best return on what they spend. And that is a far more challenging game.