Pension funds and proposed changes to legislation relating to pension funds in SA have been in the news quite a bit lately. Increasingly, members of employer pension funds and trustees are concerned that pension fund savings may be targeted by the SA government to support the dire financial position which it finds itself in. Any talk of prescribed assets (forcing pension funds to invest in, for example, government-led infrastructure development projects) sends shivers down the collective spines of ordinary pension fund members, who fear that their already (mostly) inadequate retirement provisions will be further depleted by being forced to invest in projects that may yield a sub-par return.

Although hastily retracted, the recent discussion paper on social security reform contemplating a national pension savings scheme funded through additional taxes, has opened long-standing fears that pension fund members may lose control over their pension savings. Whilst the green paper may have been withdrawn, the debate about funding national pension and health savings schemes is alive and well.

Lacklustre investment returns over the better part of the past decade, mostly because of regulations that restrict local pension funds from investing more than 30% of their assets offshore, coupled with low-growth prospects for the SA economy going forward, has not contributed positively to the way that most South Africans feel about their pension fund.

In addition, major industry surveys done locally all show that South Africans have been steadily reducing their pension fund contributions. This, coupled with a low return over the last few years and low return expectations over the next few years, means that SA is facing a pension funds crisis, which is expected to play out over the next ten to fifteen years. Industry data show that the average pension fund member is projected to retire with only around one-third of their final salary as a pension.

It is understandable then that many South Africans have fallen out of love with their company pension fund. However, is this position justified? A good starting point to assess this question, is to scrutinise what pension funds look like and how they invest in other countries.

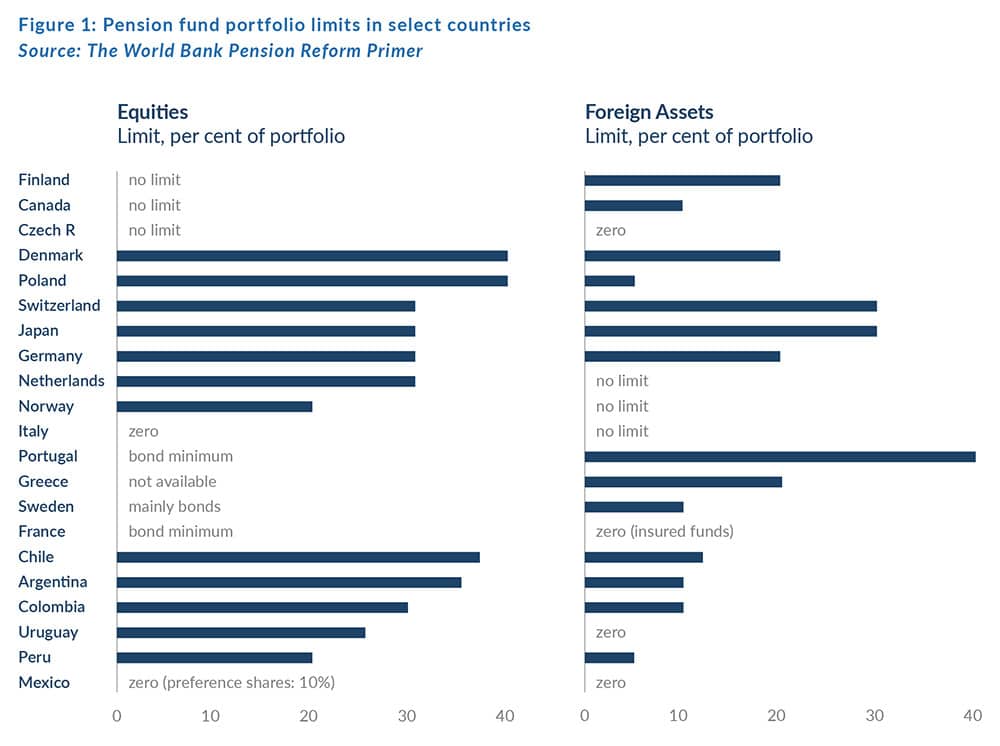

In Figure 1 below, we show the investment limits that apply to pension funds across mostly the developed world but also several major EM countries.

The first fact to note is that prescribed investment limits, such as those that apply to South African pension funds, is a worldwide phenomenon and not unique to SA.

A major complaint among South African investors has been that their pension funds are limited to investing only 30% of their total assets offshore. However, as can be seen from the data in Figure 1 above, SA allows a much greater percentage of pension fund assets to be invested offshore than most other countries, with the exception being Portugal. Among those countries highlighted in Figure 1, only Switzerland and Japan allow the same offshore limit (30%) as SA and all the other countries allow much less to be invested outside of their borders. If you consider that SA allows an additional 10% of pension fund investments to be invested in the rest of Africa (which can be invested in hard currency), then being allowed to have a total of 40% of your pension fund assets exposed to hard currency returns (US dollar, euro etc.), cannot be said to be overly restrictive.

Of further significance is that SA also allows a much higher investment limit in equities (75%) than most of the countries listed in Figure 1. If you consider that, in addition to the 75% limit on investment in equities, SA allows a further 10% to be invested in private equity and alternative asset classes, such as hedge funds, and an additional 15% in listed property, it is clear that Regulation 28 is not nearly as restrictive as many pension fund members believe it to be.

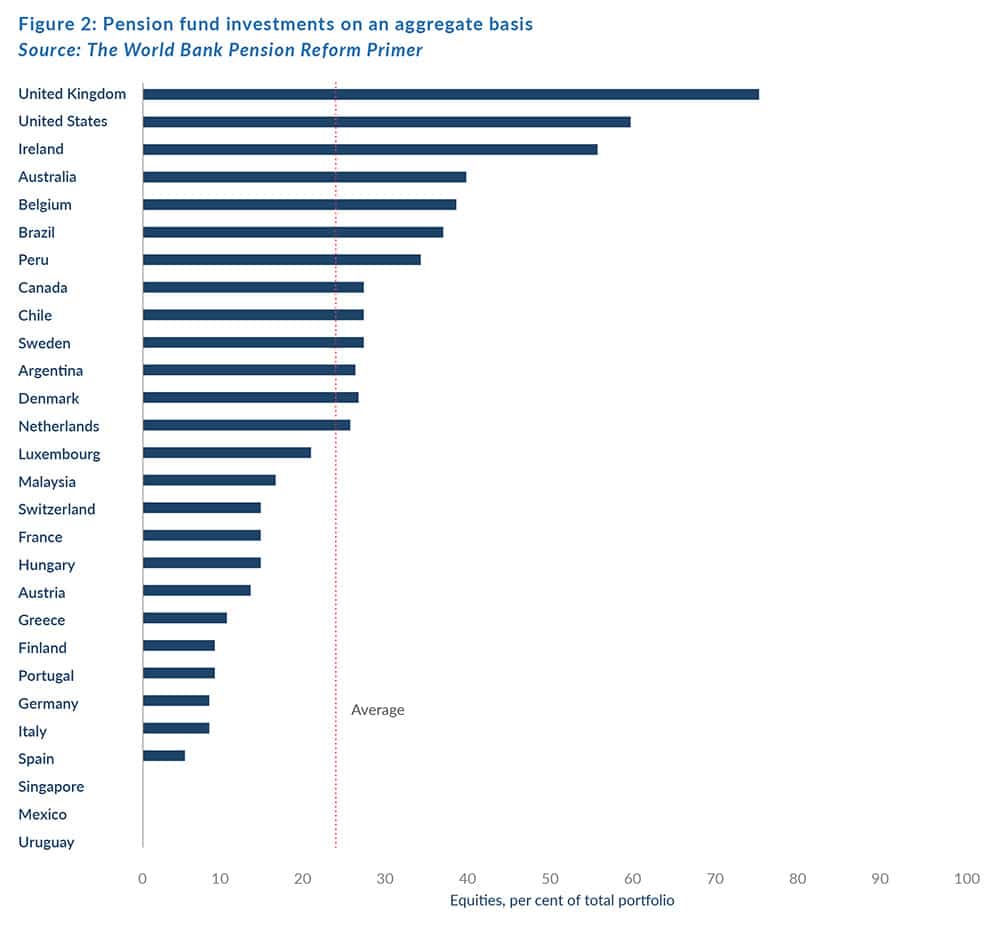

Regulation is one thing but how much members of these pension funds invest in different asset classes is even more insightful. In Figure 2 below we show the asset allocation (on an aggregate basis), followed by pension fund investments across the globe.

The typical South African pension fund follows a 70/30 asset allocation model, with roughly 70% of funds invested in equities and 30% in fixed interest instruments. This is significantly higher exposure to growth assets than is the case for most of the countries listed in Figure 2. In fact, only US and UK pension funds allocate similar percentages of their portfolios to growth assets, as is the case for most South African pension funds.

The next question that jumps to mind is how many countries employ prescribed assets in the sense that they force pension funds to invest in government instruments (such as government-issued bonds) and infrastructure development projects? The research data are too numerous to replicate here. However, quite a few countries force investment into government bonds, by applying minimum exposure levels. Examples of these countries include Austria (35% minimum), France (50% minimum), Denmark (60%) and Mexico (51%).

Conclusion

SA pension fund legislation is quite liberal and allows far greater investment freedom than most other countries around the globe. Investment freedom is also far less restricted than in most parts of the world.

In addition, the investment strategies followed by South African pension funds are more aggressive (meaning that more assets are allocated to growth investments such as equities), than is the case in most other countries.

Should a form of prescribed assets be introduced in SA, it would not be out of the ordinary either.

Tax benefits that apply to South African pension funds are significant and in-line with global norms. By way of comparison, the maximum tax-deductible pension contribution amount in the US is US$19,500 p.a., which roughly compares to the R350,000 p.a. maximum tax-deductible limit in SA.

This means that South Africans have no leg to stand on in criticising the current legislative framework for pension funds. The real question which every pension fund member must assess is how pessimistic or optimistic they are about SA’s political and economic future. These two concepts are interconnected. If SA implements reforms that support economic growth and avoids populist and socially orientated economic policy changes, then there is no reason why pension funds cannot thrive. If, however, economic reform and growth remain muted, then it is unlikely that members will see the required returns to fund their retirement.

Given the current state of the political environment, there is no clear indication of which way SA’s economic policy is likely to go. In this context, the age-old rule of making sure your investments are properly diversified should be followed. South Africans must make sure that, in addition to their pension fund savings, they also diversify their savings to include discretionary savings, both locally and abroad. Simply exclusively relying on your pension fund to provide you with retirement savings, may not be sufficient.