Almost a year has passed since what would have been the world’s largest IPO, Ant Group, was due to debut on the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges with a US$300bn valuation. Just 2 weeks after getting the green light from the securities regulator, the listing was stopped dead in its tracks as China’s Financial Stability and Development Committee (FSDC) raised concerns around technology-enabled unsecured lending. This single event would ultimately set off a rapid-fire series of regulatory interventions that would wipe out around half of the value of China’s tech sector in just 5 months.

As each passing day brings with it another unexpected pronouncement, market sentiment towards the sector has understandably turned incredibly sour. It is evident that, while there has been a lot of selling for fundamental reasons, the severely negative price action has been compounded by an equally significant level of narrative-driven selling.

After several months of digesting direct communication from China’s regulatory bodies, the opinions of those we would consider experts on the region and the impacted sectors, and the views of both the “bull” and “bear” camps – we have come to appreciate the fluid, complex and nuanced nature of the developments in China’s capital markets.

No single narrative is exhaustively descriptive and, as Western investors, it is difficult to accede to principles which are certainly at odds with our own, but which still have merit. On balance, however, we have taken a constructive view of the actions being taken by the nation’s governing bodies which, when viewed collectively, do seem to embody an underlying reform agenda that aims to curb anti-competitive corporate behaviour, redirect resources to more strategic growth industries and ensure a more equitable distribution of wealth (three structural issues that the West continues to grapple with).

With rapid growth comes growing pains…

China’s unbridled economic growth over the past two decades is a direct result of effective long-term planning, the deliberate allocation of resources and a somewhat laissez-faire approach to the rapid evolution of a new-world economy.

The anachronistic nature of the early-2000s Chinese economy birthed a modern-day gold rush for ambitious companies that would use technology to bring Western consumerism to a woefully underserved populace – in the process cementing themselves in China’s economy as “quasi-institutions”.

By way of example, Alibaba’s Alipay now processes around 54% of all mobile payments in China, and the scale of its logistics network has made it possible for merchants to send a 1kg package to any location in China within 24 hours for US$0.30. Tencent’s WeChat serves as the daily communications portal for 80% of the country’s population, and Baidu literally controls the flow of news and information from the West to the East. Life in modern China without daily interaction with these companies would simply not be possible, for both businesses and individuals alike.

Naturally, in the absence of effective intervention, this oligopolistic environment has given rise to rampant anti-competitive behaviour – and the fate of new ventures is now decided by a small grouping of giant kingmakers, rather than the natural Darwinian forces of a free market economy. As the West learned more than 100 years ago, such conditions will threaten economic growth and competitiveness – and must be addressed through actively enforced regulation.

Contrasting the value destruction against the opportunity…

However, the pace and severity of China’s “regulatory renaissance” has been jarring. Although much of what Chinese regulators have promulgated is very much in line with the agenda of Western regulators, the markedly different power structure in China allows for unilateral action and immediate enforcement.

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) recent antitrust case brought against Facebook was literally thrown out on the basis that the agency’s case lacked sufficient evidence of the company’s monopolistic position – sending the Facebook share price up another 5% on the day.

In stark contrast, on 24 July, China’s State Council announced that online tutoring businesses could no longer profit from courses on compulsory school years – effectively putting a red pen through a US$100bn industry overnight.

Such heavy-handedness has driven Chinese tech company valuations 40%-90% lower over the past 8 months, and it will be some time before we will be able to measure the impact of the new rules of the game on growth. For an investor in this space, it has been a sharp and painful experience.

We now find ourselves at an interesting juncture. As is so often the case in capital markets, an objective and pragmatic approach is almost always most valuable when it is most difficult to take – and we believe the path forward in China will again lend credence to this axiom.

The way we see it, there are two legs to the opportunity. The first being the likely transitory capitulation in China’s big tech names in the face of the regulatory barrage, and the second being the secular growth of key industries that will benefit from the same intentional redirection of capital.

Profiting from capitulation

China’s latest 5-year plan is clear – the country’s central planning authorities do not identify the consumer internet companies that have dominated global capital markets, both East and West, as strategic priorities.

The latest bout of rulemaking and the state-run media’s narrative confirm this. The “platform economy” stocks (as the State Administration of Market Regulation [SAMR] refers to businesses such as Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu and Didi) have been subject to a myriad of antitrust probes, data security control measures and restrictions implemented for the sake of “the greater good”.

The previously overlooked practices of unreported M&A transactions, forced exclusivity arrangements and the cross-subsidisation of products and services will now effectively be curbed. This will almost certainly negatively impact the near-term growth rates of the larger incumbents as they unwind these activities and incur the cost of rectification.

The challenge for investors now, is to quantify this impact in the absence of information. The earliest indications of operational impact will only start to filter through in the next series of quarterly results – and there is also always the threat of further unexpected regulatory measures. Given the high levels of uncertainty, markets are being forced to search for valuations that reflect the most bearish of assumptions and, in our view, this is where an opportunity is starting to form.

Tencent is a good example, and one that is obviously of great consequence to SA investors. The conglomerate is under pressure on several fronts, having been the subject of several of the above-mentioned actions. Add to this the authorities’ planned review of the variable interest entity (VIE) structure that facilitates Western investment into the business, and you have the perfect storm.

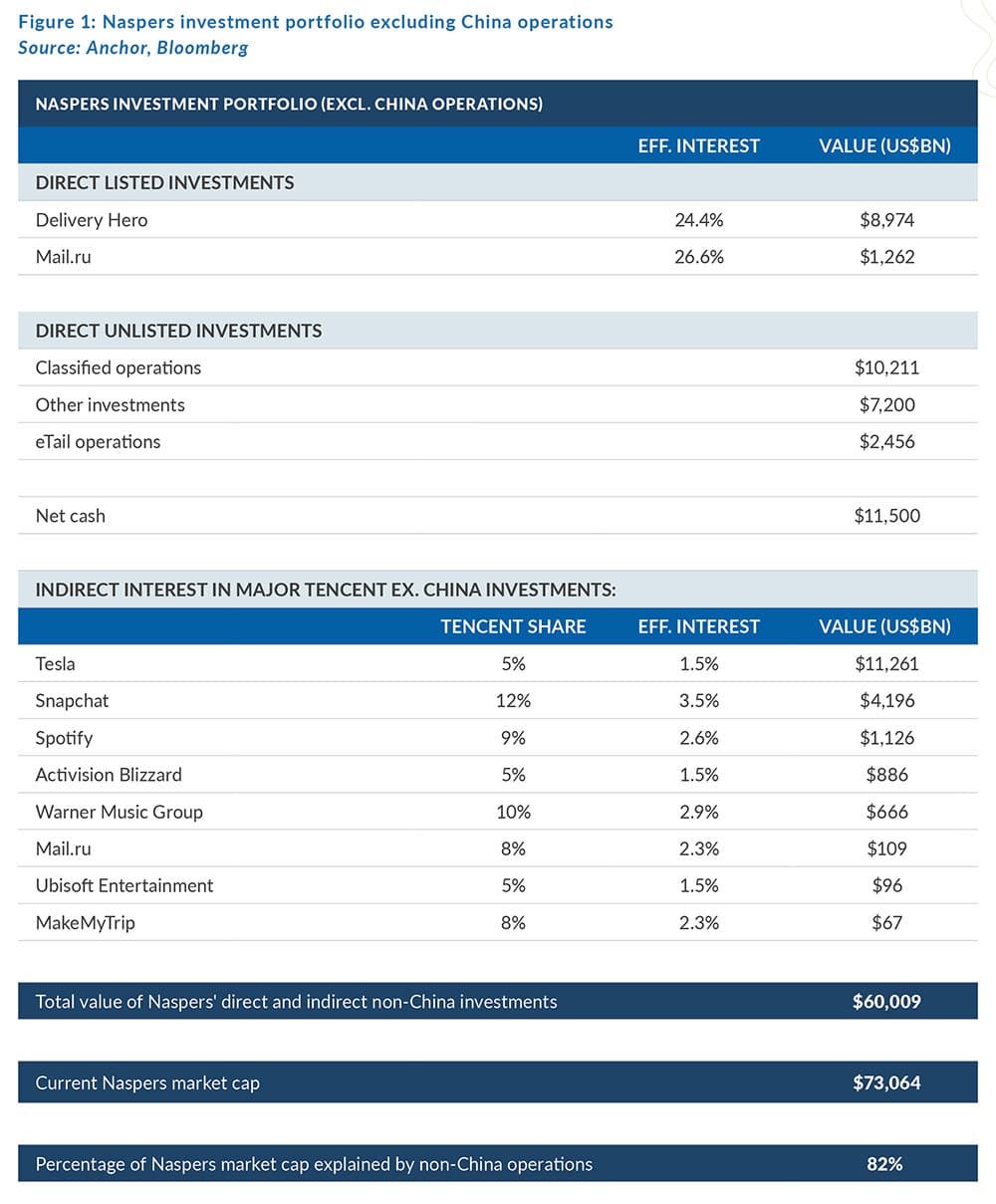

The selling pressure has been so severe, that we have now arrived at a point where – on a look-through basis – 82% of Naspers’ market cap is accounted for by the Group’s investments and operations outside of China. Granted such a calculation does not provide for a (justified) discount – but whichever way you go about it, the implied impairment to the value of Tencent’s core operations at these levels is likely bordering on the irrational.

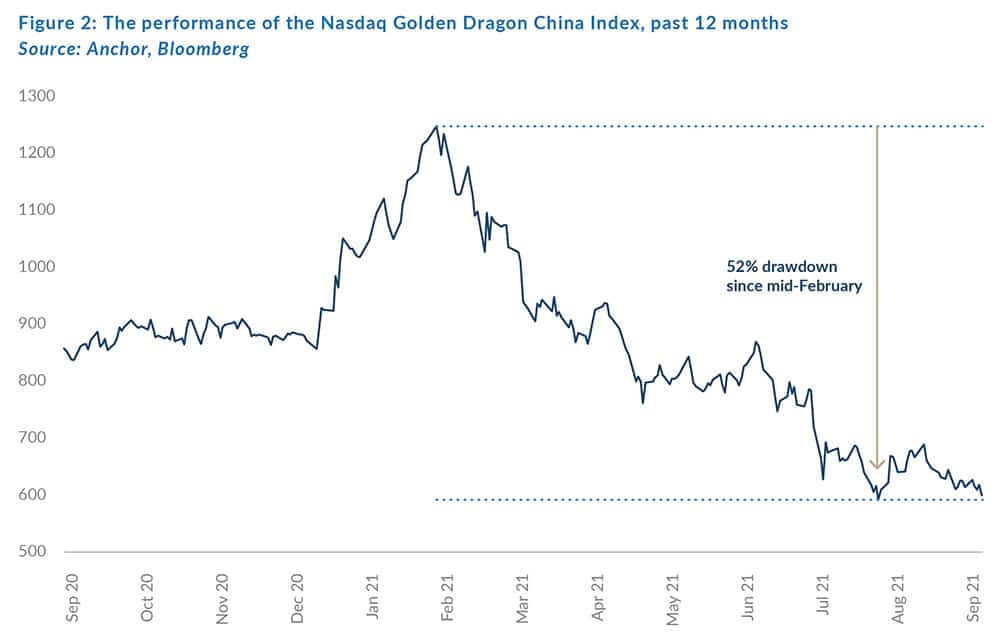

Far from being the only stock approaching what seems to be an inflection point, Tencent and Naspers are in good company. The Nasdaq Golden Dragon China Index, which tracks the performance of 99 US-listed ADRs for China-domiciled companies, is now down over 50% from its peak reached just 8 months ago. It has come to represent an “asset class” that has fallen totally out of favour.

While a deep dive into the investment merits of the constituents is beyond the scope of this article, we view it as an effective diversified proxy for the theme – with a larger weighting toward the larger, less risky platform companies and smaller exposure to the names with a high level of optionality (with concomitantly high levels of risk) such as the online education companies.

Although it may not happen for a while still, when the proverbial dust does settle – we believe the bloodletting will stop and fundamentals will once again become the primary driver of stock prices in this space, which from here would imply meaningful upside.

Investing behind secular growth

The shorter-term fallout from what has become known as the China “techlash” is obvious. Looking beyond this, the longer-term structural impact that this transformation will have on the nature of the country’s economic expansion is arguably much more significant and of far greater consequence to investors.

As we move forward, it is likely that we will witness a redirection of resources – ranging from capital to entrepreneurial efforts and even the aspirations of Chinese students – towards industries that are aligned with China’s developmental objectives.

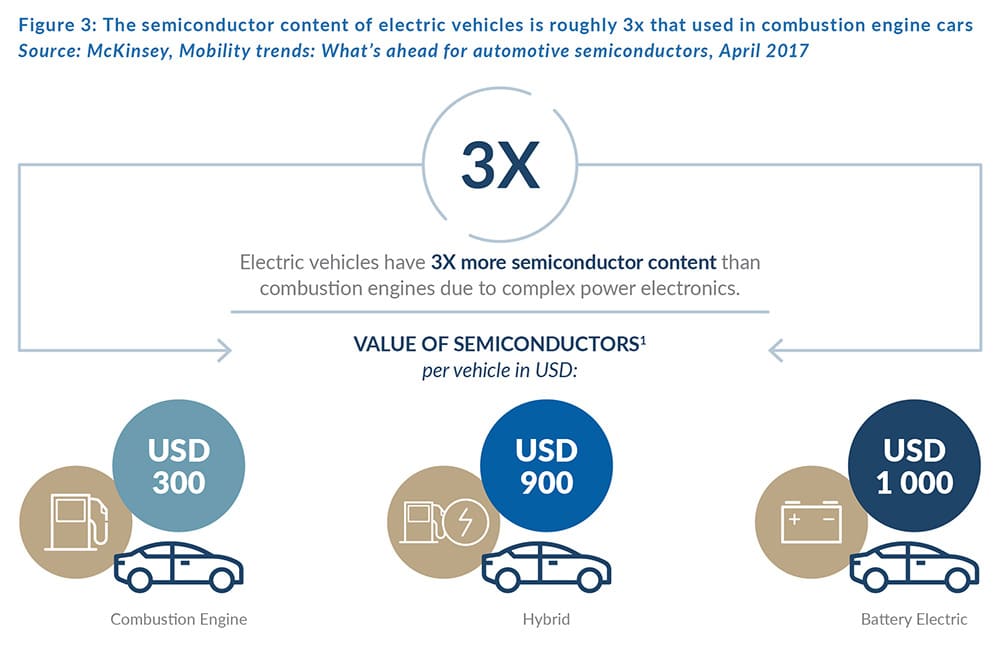

The recently published 5-year plan is explicit. China clearly wants to transform from the world’s cheapest factory into a carbon-neutral economy that will lead in high-tech manufacturing and “hard” tech disciplines. Sectors such as semiconductor manufacturing, green energy tech, genetics and biotechnology, and artificial intelligence (AI) will likely benefit from state spending and investment, regulatory support, and tax incentives – a far more attractive proposition for stakeholders than the headwinds and restrictions faced by the consumer tech companies.

We like the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest producer of computer chips, which stands to benefit from a tremendous secular tailwind as the increasing complexity of everything from vehicles to 5G base stations and data centres will drive a severalfold increase in the demand for its products.

Yum Brands China is another second-order beneficiary worth looking at, as the clampdown on living costs like education and housing will support higher levels of more basic consumption expenditure in years to come.

A rising tide lifts all boats

In what is shaping up to be a tremendous regulatory reset, China’s self-reconfiguration appears to involve enduring short-term pain for longer-term gain. The arrest of anti-competitive behaviour will almost certainly result in a healthier competitive environment, which is a net positive for cash flows and growth.

The proactive steering of resources toward more strategic industries that exhibit higher potential for secular growth makes sense and should their efforts to contain living costs prove effective – consumption expenditure could help the region wean itself off its dependence on exports.

Despite what will be a lower rate of growth over the next decade relative to the last, we still expect China’s GDP to grow in the region of 4% to 5% p.a. – a powerful tailwind for earnings growth.

Additionally, the government’s recent efforts to curb residential property speculation is likely to drive Chinese savings from property into the domestic equity markets – another significant secular force that could be supportive of equity returns in the region for years to come.