Ever since Jack Ma (the founder of China’s largest e-commerce group, Alibaba) criticised Chinese banking regulators at a October 2020 financial summit in Beijing, many of China’s largest, predominantly foreign-listed, technology (tech) companies have experienced regulatory interventions, which have severely curtailed or, in some cases, eliminated their profit-making opportunities. In this note, we summarise what happened, try to contextualise the regulatory interventions, and we discuss the way forward for investing in Chinese public companies.

Executive summary

What happened?

- Ant Financial’s much-hyped November 2020 initial public offering (IPO) was scrapped after its founder, Jack Ma criticised regulators in a speech made days before the planned IPO. Regulators later forced the company to convert to a financial holding company.

- In February this year, government officials started discussing possible regulatory interventions in other sectors of the economy including online gaming and online tutoring.

- In July 2021, during the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) centenary celebrations, the regulatory crackdown gathered momentum and interventions included the withdrawal of Chinese ride-hailing app, DiDi Chuxing from app stores just days after its US$4.4bn US IPO.

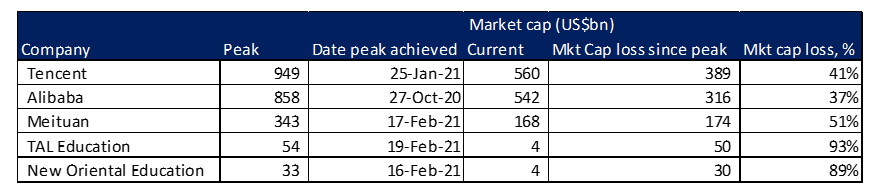

- Five of the largest, and most directly impacted, Chinese companies have lost US$1trn in value between them, from the peak valuations they achieved shortly before they began to experience regulatory intervention to now.

Why did it happen?

- Initially, the regulatory interventions appeared to be an attempt by the Chinese government to reassert its authority on a private sector which was getting too powerful for its liking, while the targeting of foreign-listed companies seemed to be a part of the ongoing US-China spat.

- With the benefit of hindsight, the regulatory interventions coincided with a shift in strategic focus for the government, which rolled out its latest five-year plan in March this year.

- Having successfully achieved its strategic goals of poverty eradication and increased urbanisation and urban employment during the previous decade, the government has shifted its focus to addressing increasing inequality, a side-effect of the unchecked economic growth used to achieve its previous strategic objectives.

How do we approach China from an investment perspective going forward?

- The latest five-year plan commits to increased access to Chinese capital markets, so the opportunities to invest in China’s economic growth will expand rapidly.

- Diversification is key when the government is willing to sacrifice companies in industries that do not align with its strategic objectives.

- Having a long-term mindset is critical to ride out the cycles of regulatory tightening.

- We would advise investors to focus on those areas with long-term strategic tailwinds.

- Avoid those companies which have a business model at odds with the long-term strategic goals of the Chinese government. Or, at the very least, reassess the future profitability and growth potential of these companies to see if their current valuations adequately reflect their new reality.

- The incumbent’s ability to leverage its superior data set as a competitive advantage to expand into adjacent industries will become increasingly difficult, so a passive approach (which is typically overweight the internet companies that have dominated over the past decade) is unlikely to be particularly successful going forward.

- If China is successful in achieving “common prosperity”, its economy should increasingly rebalance towards consumption and, perhaps, the simplest way to benefit from that trend will be to back those companies that are most likely to capture a disproportionate share of the increasing consumption (which might very well be global consumer companies and not necessarily domestic Chinese companies).

What are the biggest areas of uncertainty?

- The implementation of new policies is still being flushed out, so we should be prepared to experience some additional regulatory intervention, which may very well increase negative sentiment around China’s investment case.

- The success of the implementation relies heavily on successful innovation. Innovation, though, is inherently uncertain and, as such, is unlikely to just happen at the whim of central control.

- In October 2022, when the CCP holds its 20th National Congress (NC), if incumbent President Xi Jinping is unsuccessful at clinging to power, there is a strong possibility that the new leader will take a different approach to interpreting and implementing the long-term strategic goals for China, which is likely to result in another period of sustained regulatory intervention.

What happened?

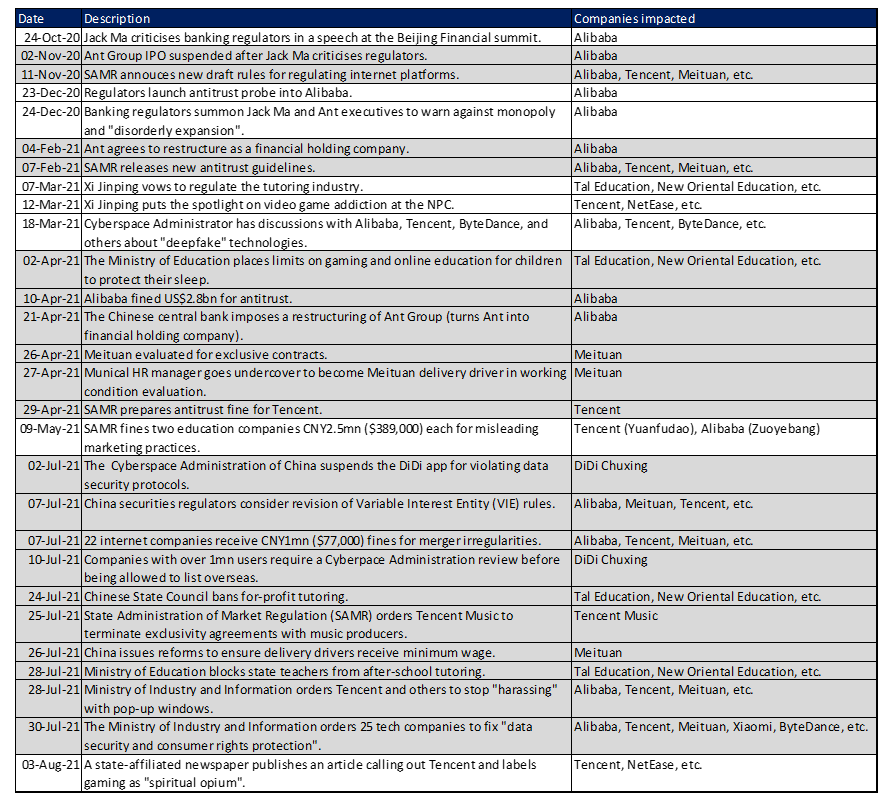

Ant Financial Group, the fintech arm of Alibaba Group, was due to go to an IPO in Hong Kong and Shanghai on 5 November 2020, with the firm expected to raise US$37bn, valuing the company at c. US$300bn. This would have seen it overtake the US$29.4bn IPO of Saudi Aramco in 2019 to become the most valuable IPO ever. However, Ma’s criticism of Chinese regulators just 12 days before the IPO ultimately saw the IPO scrapped and the company forced to convert into a financial holding company with significantly higher capital requirements and regulatory constraints. This also prevented it from using the rich dataset of Alibaba numbers to further its lending business. The initial regulations seemed squarely aimed at punishing Ma for daring to challenge the Chinese government but, in February 2021, the narrative started to expand as the regulatory crackdown gathered momentum and spread to other tech sectors including the lucrative gaming and online tutoring markets. This all happened in the lead up to China’s most important political meeting of the year in March – the “lianghui” (“two sessions”), which refers to the annual meeting of that country’s top legislature, the NPC and its political advisory body, the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). The lianghui ultimately saw the approval of China’s fourteenth five-year plan, which lays out the strategic priorities for the country over the next half decade (as well as some longer-term goals for 2035). Regulatory intervention seemed to slow in the wake of the “two sessions” but then in July, as the CCP was celebrating its centenary, the regulatory interventions started to accelerate including a clampdown on Chinese ride-hailing company, DiDi Chuxing, which saw its app being pulled from app stores by Chinese regulators over data security concerns just days after its US$4.4bn US IPO.

Figure 1: Timeline of recent Chinese regulatory interventions

Source: Anchor

Investors were, unsurprisingly, spooked by the regulatory interventions which had a significant impact on the market value of these companies, with five of the largest and most directly impacted companies seeing their combined market caps fall by c. US$1trn from their respective peaks (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Five of the largest, and most directly impacted, companies lost US$1trn in value between them

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

Why did it happen?

Cynical investors might interpret the interventions as the Chinese government’s attempt to reassert its authority on a private sector which was getting too powerful for its liking and, perhaps, used the opportunity to kill two birds with one stone and ensure the damage was most acutely felt by foreign investors in another shot fired in the US-China rivalry. What has become clearer with hindsight is that this is more likely the initial implementation of the latest long-term strategic initiatives of the CCP as its shifts focus to its new policy direction.

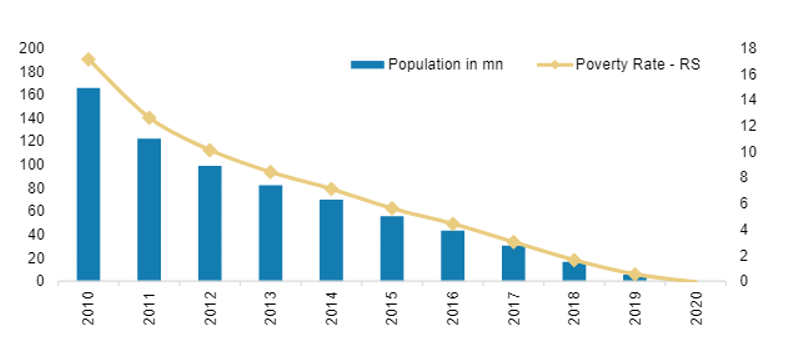

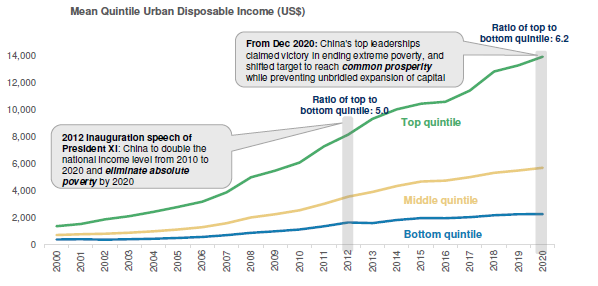

The past decade has seen China successfully meet its goals of alleviating poverty and improving living conditions. 160mn people have been lifted out of extreme poverty over the past decade (c. 100mn of those people have been lifted out of poverty during President Xi Jinping’s reign [since 2012]).

Figure 3: China has successfully eradicated poverty over the past decade

Source: CEIC, Wind, Morgan Stanley Research

The shift to urban areas has also been accompanied by increased employment, with 60mn jobs having been created in urban areas in the past 5 years.

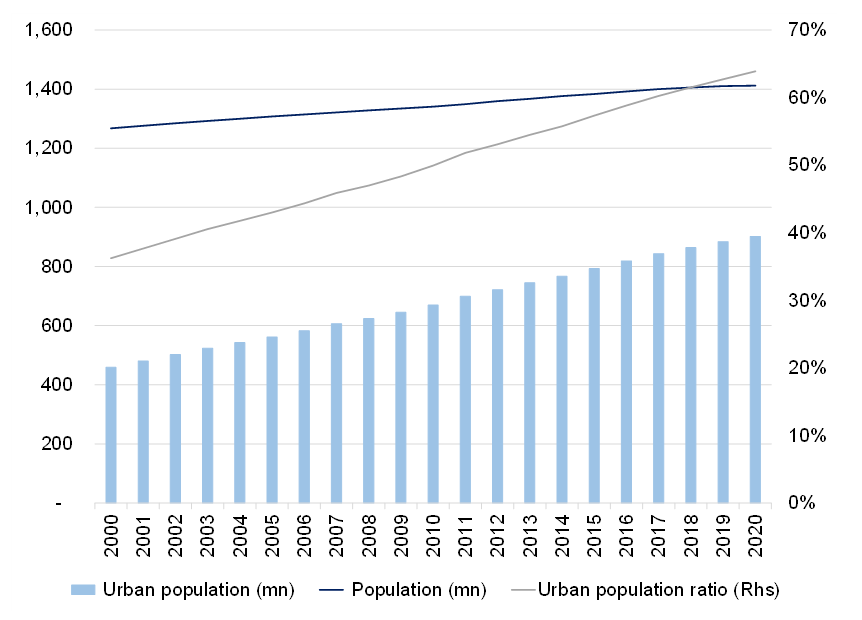

Figure 4: The past decade has seen c. 230mn people relocate to urban areas in China

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

The policies that enabled the rapid economic growth have clearly played a significant role in achieving the strategic goals of government over the past decade, but it has become clear that unchecked economic growth has come at the cost of increasing inequality.

Figure 5: Rapid economic growth has alleviated poverty in China but also increased inequality

Source: CEIC, Wind, Morgan Stanley Research

China’s latest five-year plan is an attempt to address some of the challenges created because of the unchecked economic expansion. The goals required to achieve “common prosperity” can be broadly categorised as follows:

- Social and economic stability

- Address income inequality (the balance between corporate profits and wages).

- Ease the time and monetary burden of education.

- Enhance elderly care and reduce medical costs.

- Increase insurance coverage (and reduce the need for precautionary savings).

- Protect consumers from predatory/monopolistic behaviour.

- National security

- Enhance data security (particularly as it pertains to foreign listings).

- Ensure supply chain self-sufficiency (including semi-conductors).

- Strengthen cyber security.

- Financial stability and sustainability

- Curb regulatory arbitrage.

- Contain leverage (including in the property sector – “property is for living not for speculating”).

- Promote foreign direct investment (FDI) and increase financial market liberalisation.

- Environmental sustainability

- Reach peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

- Geopolitical stability

- Increase China’s role in regional and global economic policy.

- Manage rivalry with the US.

Some of the recent regulations fit neatly into these themes and, even though the Alibaba regulatory challenges preceded the approval of the latest five-year plan in March this year, the process of drafting the plans began in March 2020 and were approved for drafting at the fifth plenum in October 2020, so Ma’s comments likely only accelerated the actions against Alibaba. These goals are fairly broad and quite philosophical, so the implementation is not always obvious, but the latest regulatory crackdown gives us a good idea of the areas that are most likely to be in focus.

How do we approach China from an investment perspective going forward?

First, we should not panic, what is at play is clearly not a bunch of random acts of government “muscle-flexing” or another salvo in the tit-for-tat battle for global supremacy with the US. In fact, as investors, we should welcome the long-term strategic thinking that will likely deliver sustainable growth, which is a key element of successful long-term investment returns. The latest five-year plan also commits to increasing access for foreigners to Chinese capital markets, so the breadth of investment opportunities is going to keep growing. That said, there are definitely some learnings we can take from this.

- Diversification is key when it comes to China

It is clear that China is willing to sacrifice areas that do not align with the country’s long-term goals and that can have catastrophic consequences for individual companies focused in niche areas (e.g., after-school tutoring). While the warning signs are perhaps obvious in retrospect, there are often compelling arguments as to why these warning signs should be ignored (“surely China wants its populace to be the most highly educated in the world?” might have kept you invested in after-school tutoring, despite warnings from government of an imminent crackdown in the sector). The message of diversification might be a tough one for South African (SA) investors whose easiest access to Chinese investment opportunities is in the form of Tencent (via Naspers and Prosus), but this speaks to the importance of rather looking for suitably diversified offshore investment solutions instead of trying to create a globally diversified portfolio via JSE-listed counters.

- Having a long-term mindset is critical. Regulatory policy is likely to be a recurring theme for investors looking for Chinese investment exposure. Investors need to have the patience to ride out the cycles of regulatory tightening.

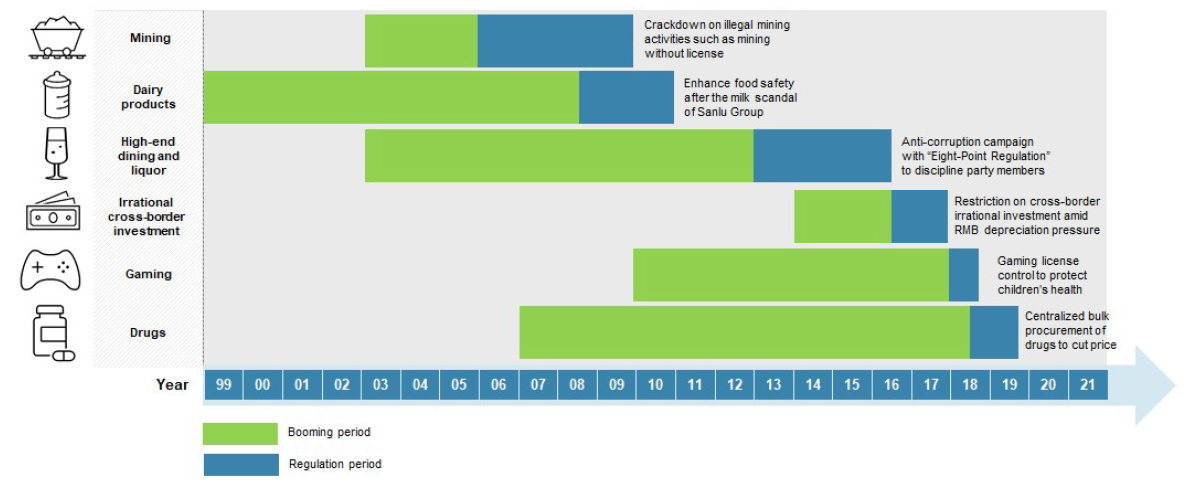

We have probably experienced a period of unusually limited government intervention in China, as cyclical challenges related to the trade war and then the pandemic saw the Chinese government back away from any intervention that would add stress to an already uncertain economic environment. Having said that, it is not unusual for there to be a level of cyclicality to Chinese government intervention. We recently hosted a webinar entitled Let The Bullets Fly – China’s regulatory crackdown and the impact on tech counters, with Chinese tech commentator, Lillian Li, who characterised the Chinese approach as “innovate and then regulate” and we think it is important to have that context when dealing with China. China’s long-term strategic focus, and central control, lends itself to occasional “course corrections” as sectors fluctuate between:

- A relaxed stage: Local government support, pro-growth mentality, and business interests together contribute to a lag in regulating emerging sectors; and

- a tight regulation stage: When a problem is looming as evidenced by public opinion and/or financial stability indicators, the top leadership shifts gears, quickly mobilises all of its administrative resources to reorientate its policy control and bolster its regulatory capacity.

Figure 6: China’s pattern of “innovate and then regulate” leads to periods of booming activity followed by regulatory intervention

Source: Morgan Stanley

- Focus on the areas with long-term strategic tailwinds.

China has been reasonably clear about the areas that will experience government support over the next few years, these include:

- Innovation – looking to avoid the middle-income trap by increasing innovation and shifting to higher value-add manufacturing, while also securing technological self-sufficiency:

- Tech localisation – next-generation artificial intelligence (AI), semiconductors, cloud computing, and others.

- Advanced manufacturing – including a focus on robotics, new energy vehicles, aircraft development, and agricultural machinery. Manufacturing companies to get a 100% tax deduction for research and development (R&D).

- Accelerating the drive towards a low-carbon economy. The government is expected to issue a separate five-year plan for energy soon, but the current plan includes:

- Increasing nuclear power by 40%.

- Bolstering energy security by securing China’s coal supply and expanding production of crude oil and natural gas.

- Avoid companies whose business model is at odds with the long-term strategic goals of the government.

Or, at the very least, reassess the future profitability and growth potential of these companies to see if the current valuation adequately reflects their new reality. This might include companies that:

- Rely disproportionately on cheap labour or where workers experience particularly harsh working conditions.

- Are gaining market share because of regulatory arbitrage (e.g., fintech and decentralised finance).

- Are taking advantage of, or manipulating, their customers through misleading advertising or predatory marketing techniques.

- Are providing products that are harmful to the health and well-being of the Chinese population (particularly to the extent that it impacts the youth).

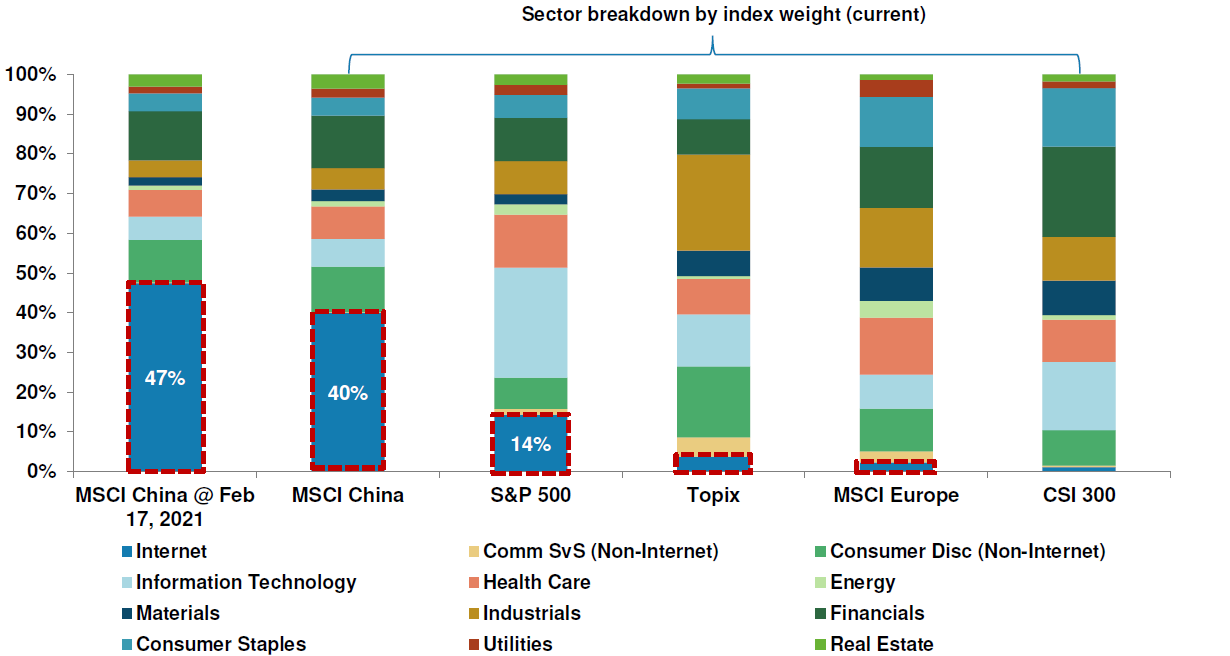

- The incumbent’s ability to leverage their superior data set as a competitive advantage to expand into adjacent industries will become increasingly difficult.

Unlike the previous decade, it is less likely that backing market leaders will be a winning strategy as the incumbents face increased antitrust and data security scrutiny. This also suggests that a passive investment approach to China (which is generally overweight the current market leaders) might not be the best approach.

Figure 7: Increased antitrust and data security scrutiny is likely to result in internet companies (which currently represent a disproportionately large share of Chinese equity market) underperforming in the next cycle

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

In general, if China is successful in achieving “common prosperity”, the increasing affluence and urbanisation should also achieve the aim of increasing consumption as a share of economic activity in China. So, perhaps the simplest way to benefit from that trend will be to back those companies that are most likely to capture a share of that increasing consumption, which might very well be global consumer companies and not domestic Chinese companies.

What are the biggest areas of uncertainty?

It is clear that we are still very early in the rollout of China’s latest five-year plan, so the way the government implements and interprets the policies is still very much a work in progress. Thus, we should be prepared to experience some additional regulatory intervention, which may very well increase negative sentiment around the Chinese investment case. That said, it seems to us that most of the surprises are likely to be at the margins, with the broad aims of the party starting to become much clearer and, as such, are likely already priced in to current valuations.

The success of the implementation is also a key risk as the government’s plan to avoid the middle-income trap relies heavily on successful innovation. Innovation, though, is inherently uncertain and, as such, it is unlikely to just happen at the whim of central control.

Perhaps the biggest threat lies in the upcoming elections in October 2022, when China holds its 20th NC. Xi Jinping has paved the way for an unprecedented, third 5-year term as president by abolishing term limits in 2018. If Jinping is unsuccessful at clinging to power, there is a strong possibility that the new leader will take a different approach to interpreting, and implementing, the long-term strategic goals for China, which is likely to result in another period of sustained regulatory intervention.