Markets obsess about one thing at a time. Remember when the euro crisis dominated the collective consciousness as we waited for the dominoes to fall … first Greece, then Spain, Italy, and France? What about COVID-19? Cast your mind back a year, with the global economy in a self-induced coma and markets in freefall. Did anything else matter? In the moment, nothing else did and it was difficult, if not impossible, to maintain perspective.

These episodes appear relatively benign in the rear-view mirror, an obvious buying opportunity. Could they have turned out differently? Absolutely. And yet, one can reasonably conclude, even without the benefit of hindsight, that the odds and potential pay-off were highly favourable at the time. As investors that is about as much as we can ask for and act on.

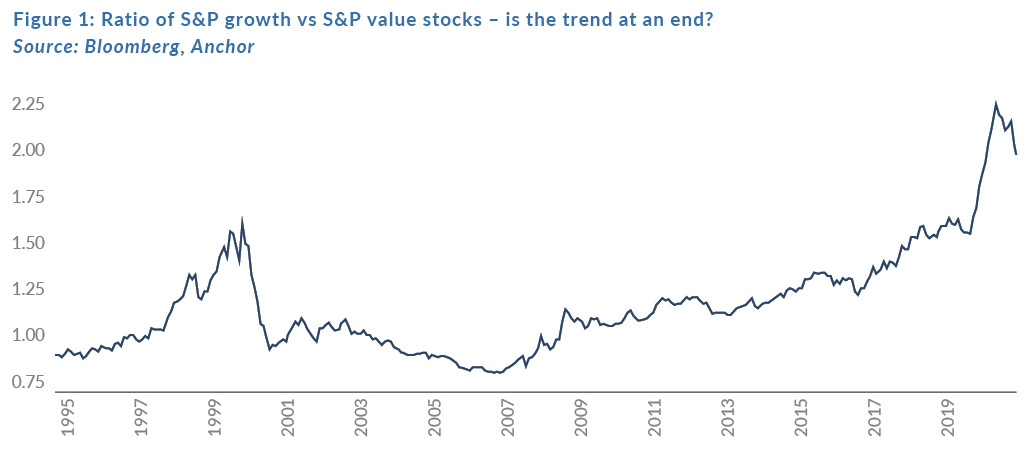

What is the market obsessed about today? The return of economic growth, inflation, and rising interest rates. The dominant narrative is that this environment is good for value stocks and cyclical shares, and bad for growth stocks. After a decade of outperformance, investors are asking whether this represents the sunset for growth and a new dawn for value.

Although we generally find the growth vs value distinction arbitrary, our holdings are nevertheless biased towards the former group. Are we on the wrong side of history?

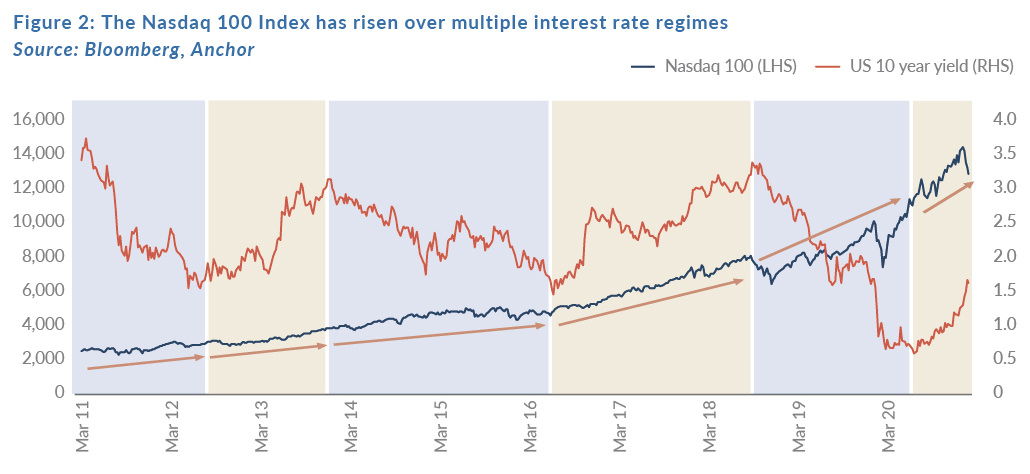

The data do not support the narrative. In Figure 2 below, we highlight the Nasdaq Index (dark blue line, intended to represent technology and growth stocks) and the US 10-year yield (red), while the shaded light blue and beige areas represent periods of falling and rising interest rates, respectively. Over the past decade, the Nasdaq rose irrespective of the direction of interest rates.

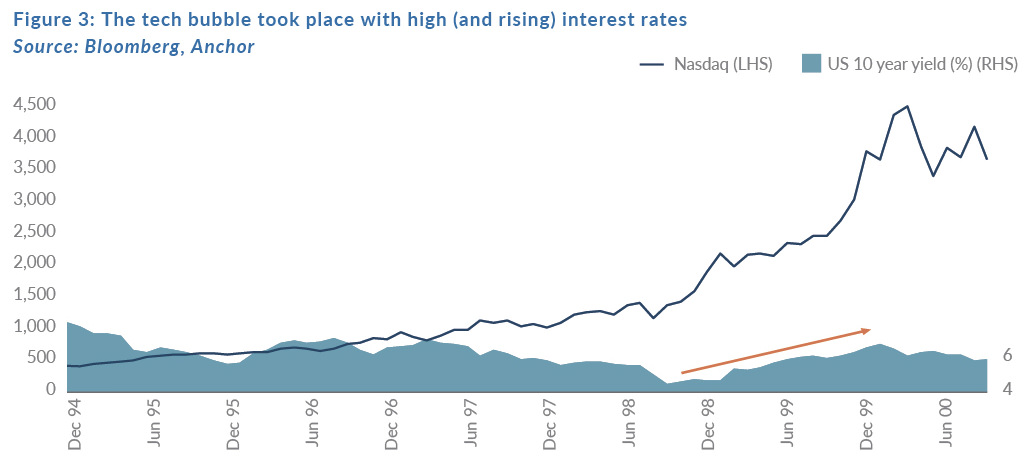

We also note that the technology bubble took place in an era of 6% interest rates. Equally noteworthy is the fact that the steepest part of the ascent came as yields rose from roughly 4% to 6%.

Growth stocks became a crowded trade as COVID-induced uncertainty peaked. As vaccines were announced and countries gradually re-opened their economies, investors rotated into the sectors that would benefit from a return to normal. According to JP Morgan’s proprietary ‘crowding indicator’, growth stocks have recently experienced one of the largest unwinds in positioning in over three decades. Bank of America’s March 2021 Fund Manager Survey revealed a wholesale rotation into cyclical sectors, while participants’ technology sector holdings had been cut to the lowest level in over a decade. Investors were more bullish on the outlook for value stocks than at any point in the survey’s almost 15-year history. To the extent that value and cyclicality represented a high odds, favourable pay-off bet in mid-2020, that is less likely the case today.

The recent setback in growth stocks, while painful, is arguably both necessary and a (long-term) positive. First, the fact that the rally has broadened out across sectors is a healthy sign and may result in a more durable bull market. An unchecked parabolic run in a narrow group of stocks, much like the tech bubble, is unlikely to be sustainable. Second, it is an almost immutable law that the market demands its pound of flesh from investors. There can be no ups without downs and no highs without lows. Some will fail the latest test, while the strong hands will go on to reap their reward.

The Anchor Global Equity Fund is focused on a subset of growth stocks, called multibaggers. These are the elite of the elite, the companies (and shares) with the potential to increase by multiples of their current size over the next 5 to 10 years. Over shorter time horizons, these shares are prisoners of their labels; when the algorithms sell baskets of technology and growth shares, our holdings do not escape unscathed. Longer term, however, we believe each share will rise (or fall) on its own merits.

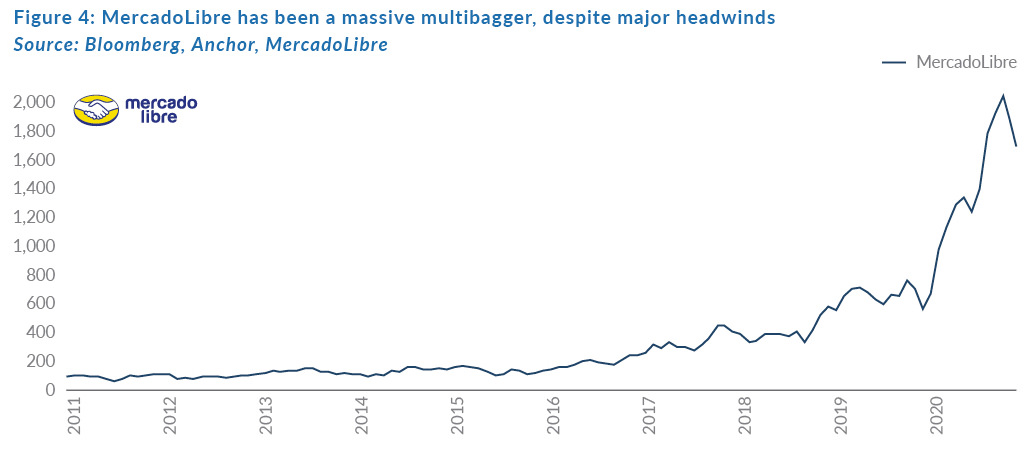

Take MercadoLibre, the Amazon of Latin America, as a case in point. Headquartered in Argentina, MercadoLibre has operated in countries with hyperinflation, stagnant economic growth, and chronically weak currencies. And yet, despite a host of seemingly insurmountable challenges, the stock has risen 20-fold (in US dollar terms) over the past decade. A narrow focus on macro variables (or factor labels) would almost certainly have led to the wrong investment decision.

Over the next decade, the success of our holding in Sea Limited will depend on whether the company can press home its leading position in ecommerce in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian markets. Likewise, Snap’s returns will hinge on its ability to deliver engaging augmented reality experiences to both consumers and advertisers. And if Etsy can provide more shoppers with a greater selection of unique, handcrafted items, we believe its shares will deliver a pleasing performance. What is less likely to matter, for these companies and the rest of our holdings, is the direction of interest rates or their classification as either growth or value counters.

Shorter term, the sentiment and positioning pendulum may have swung to the point where growth stocks offer better odds and a superior payoff vs value stocks. Longer term, the question of growth vs value is largely irrelevant. Rather, we are placing our bets on founder-led companies that are building great products and growing rapidly. We are looking for the next MercadoLibre. The market will inevitably move on to a new obsession, but the sun will never set on multibaggers.