Executive summary

- China is the largest and fastest-growing market for luxury goods.

- The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) latest strategic goals include an ambition to double the middle-income cohort by 2030, increasing that demographic (which is the most prolific purchaser of luxury goods) by c. 7% p.a. for the next decade and thus providing a strong structural tailwind to luxury goods purchases for the long term.

- The shifting Chinese regulatory environment is likely to include the introduction of taxes that will diminish the disposable income of luxury goods purchasers. These taxes are likely to be applied in a measured fashion over the next few years, which may slightly dilute the structural drivers of above-average luxury goods purchases in the short- to medium-term.

- Caution around conspicuous consumption in an environment where government is focussed on moderating excesses may weigh on luxury goods purchases over the short term. However, the Chinese government seems more focussed on how wealth is generated, rather than preventing people from becoming wealthy. Thus, consumers with wealth generated in sectors facing government scrutiny may pull back conspicuous consumption in the short term but that is likely to be partially offset by consumption from wealth generated in those sectors being supported by the CCP’s strategic goals.

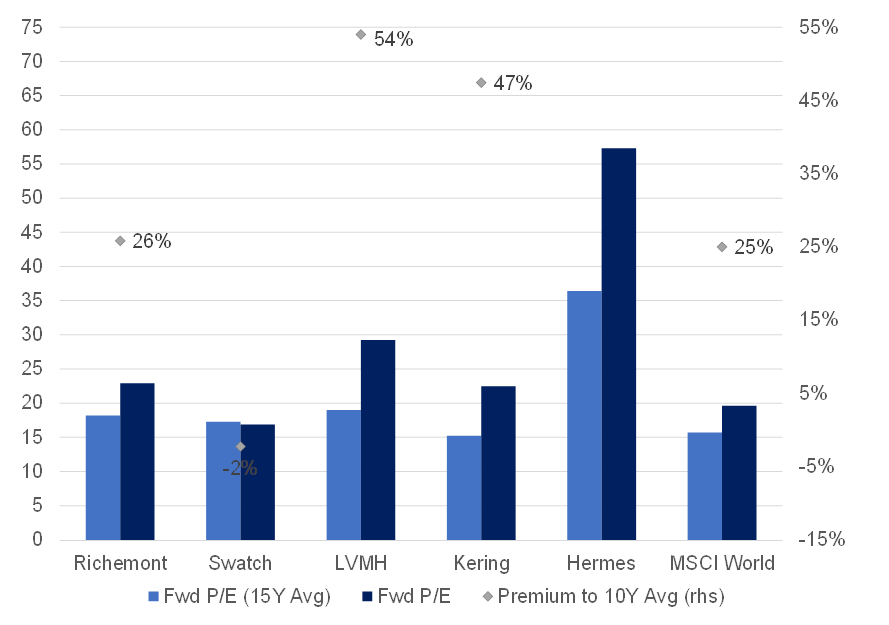

- Luxury goods companies are trading at a meaningful premium to their historic valuations, but that is also the case for the entire market, largely because of historically low interest rates. The premium that luxury goods companies trade at, relative to the broader market, is largely in line with their historic premium.

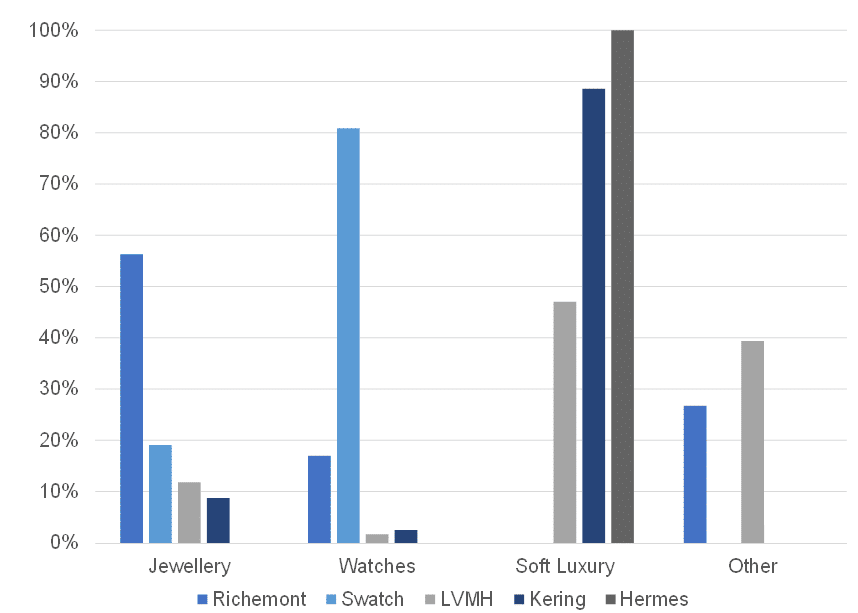

- Soft luxury goods (leather goods and fashion) have enjoyed superior growth and wider margins than hard luxury goods (watches and jewellery). As a result, luxury goods companies with sales skewed to soft luxury (LVMH, Kering and Hermes) are looking relatively more expensive (compared to their own historic valuation premium) than those companies with predominantly hard luxury goods sales (Richemont and Swatch).

China is the largest market for the luxury goods sector

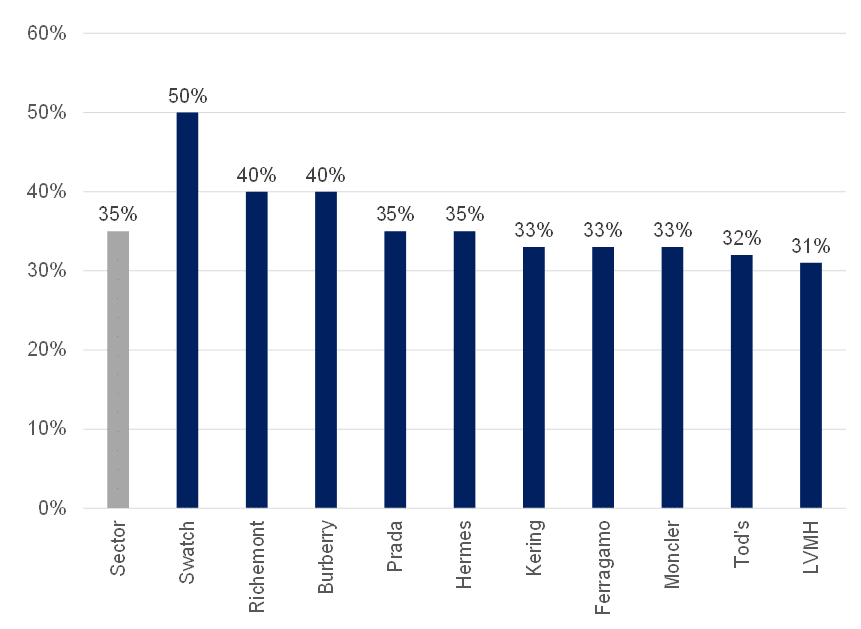

Figure 1: Exposure to Chinese consumers as % sales (2019)

Source: Anchor, UBS Estimates, company data

China’s transition to its 14th five-year plan has caused considerable pain for many stocks believed to be on the wrong side of shifting Chinese regulatory changes. The luxury goods sector is the latest to see a significant derating as Chinese media reported that President Xi Jinping suggested it might be necessary to “reasonably regulate excessively high incomes” in the search for “common prosperity”.

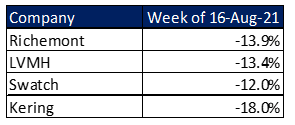

Figure 2: The share price performances of luxury goods companies in the week following President Xi Jinping’s comments

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

Concerns that Chinese consumers might shy away from “conspicuous consumption” on luxury goods to avoid drawing attention to their wealth or that the government may introduce redistributive taxes that would siphon off disposable income otherwise available for luxury goods purchases are at the heart of the most recent derating.

Common prosperity as a driver of long-term structural growth

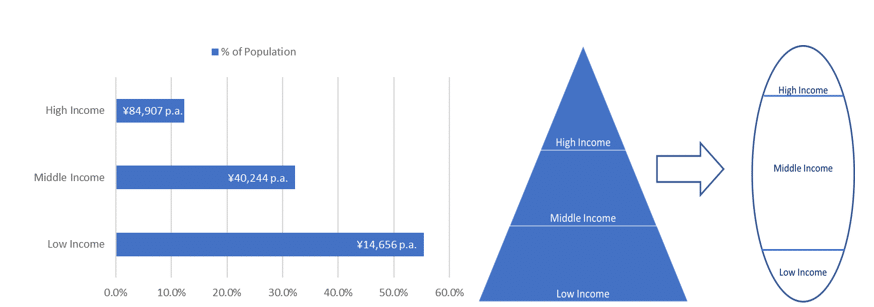

Common prosperity, at its heart, has the goal of minimising the proportion of both high- and low-income sectors of the population.

Figure 3: Shifting China’s income distribution from “pyramid-shaped” to “olive-shaped”

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg, National Bureau of Statistics of China

If China meets its goal of an “olive-shaped” income distribution, this will see China’s middle-class population double over the next decade.

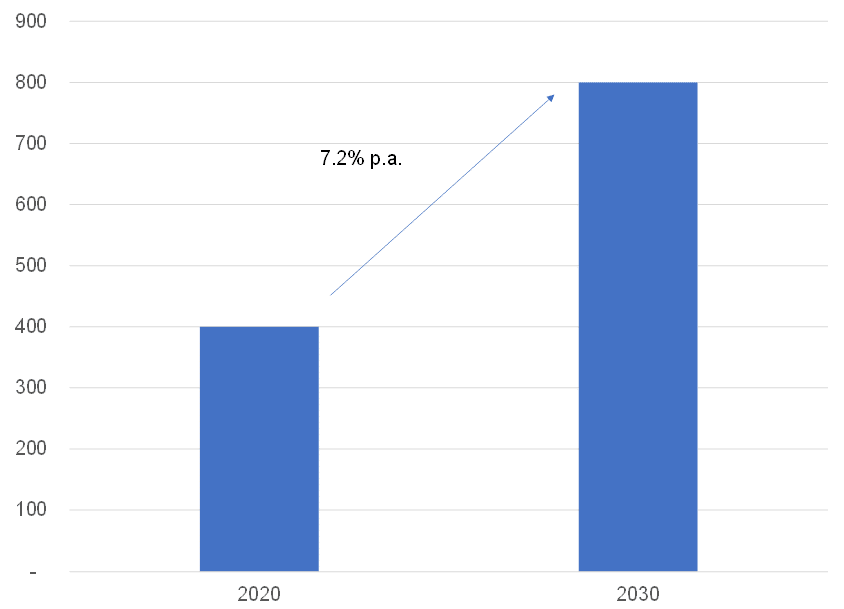

Figure 4: China aims to double its middle-income population over the next decade

Source: Anchor, Morgan Stanley

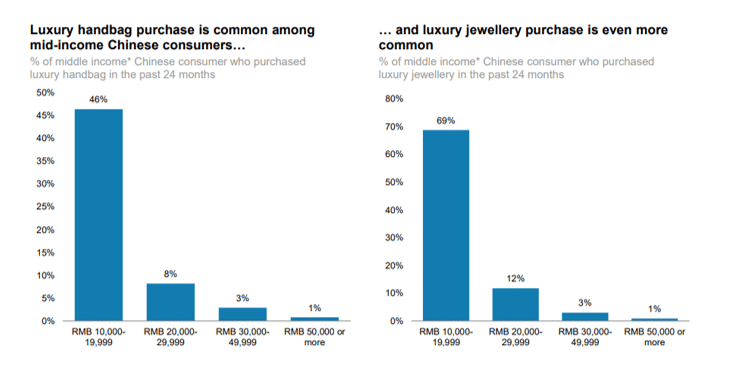

Survey data from Morgan Stanley and AlphaWise suggest that Chinese middle-income consumers are in fact the most prolific purchasers of luxury goods. So, from that perspective, we believe that the process of achieving common prosperity in fact provides a meaningful structural tailwind to luxury goods spending over the next decade.

Figure 5: Morgan Stanley AlphaWise survey data suggest that Chinese middle-income consumers are the most likely income group to make regular luxury goods purchases

Source: Morgan Stanley, AlphaWise

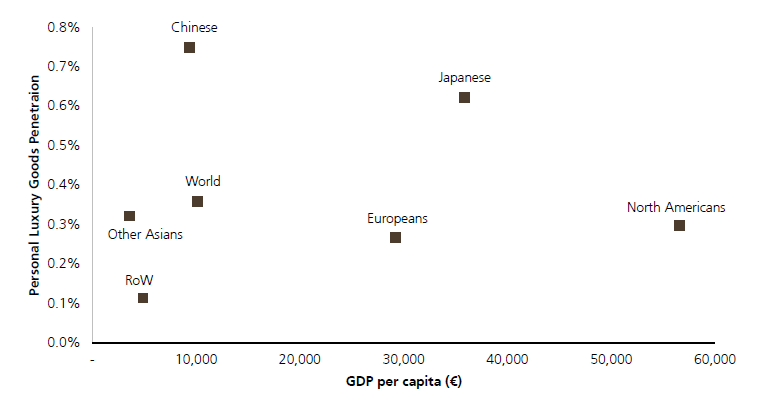

Chinese consumers also tend to start to buy luxury at a lower level of income compared with other nationalities, as illustrated by UBS analysis of luxury penetration by nationality.

Figure 6: UBS estimates of luxury spend penetration* by nation (2019)

Source: UBS estimates, Bain-Altagamma Luxury Study, World Bank. *Luxury spend penetration is defined as luxury spend/GDP

Taxes as a short-term headwind to luxury spending

We expect tax changes to be gradual and the emphasis to be on increasing household income and improving basic public services and social protection rather than major income redistribution. Policy guidelines for Zhejiang’s pilot programme are very much along these lines.

a) Personal income tax represents c. 5% of Chinese tax revenue (relative to the c. 24% average for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] countries) and is regressive (i.e., no sliding scale), so this system needs to be reformed, but any implementation is likely to be slow given the broad impact this is likely to have on the population and, by extension, on the popularity of the NPC. Any increased personal income tax burden is unlikely to fall excessively on the middle-income cohort given the government’s goal to incentivise accession into middle income.

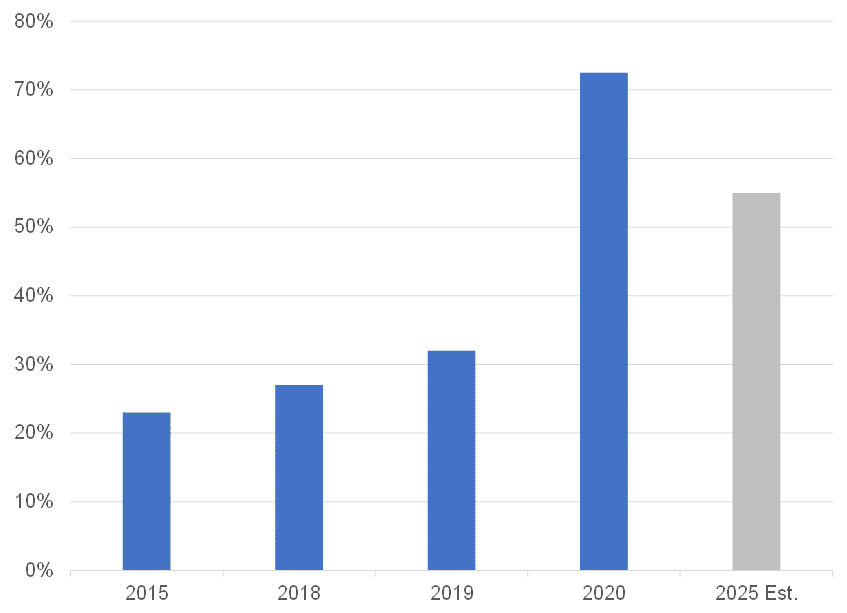

b) Consumption tax: The Chinese tax system is heavily reliant on consumption tax (c. 41% of tax revenue relative to the c. 31% average for OECD countries) and coverage is relatively narrow (predominantly alcohol, tobacco, fuel, automobiles, and some luxury goods). The system of collection is heavily skewed towards collection on production/import rather than wholesale/retail. It is likely that this will shift towards a broader coverage of goods and collection at the retail stage, though the impact of this approach is likely to be felt most acutely by lowering the tax revenue in the poorer manufacturing regions, so rollout is again likely to be slow to minimise the impact. From 2018 to 2020, the Chinese government moved to cut import duties on jewellery and increased tax-free allowances in its efforts to support the onshoring of Chinese luxury goods purchases and it seems unlikely that there will be a major U-turn on these policies.

Figure 7: The proportion of Chinese nationals’ luxury goods purchases effected in mainland China

Source: Anchor, Bain-Altagamma 2020 Worldwide Luxury Market Monitor

c) Property tax: This is a much-discussed tax, which has been trialled in Shanghai and Chongqing since 2011 but was not discussed in the 2021 NPC meetings and is also not included in this year’s legislative schedule. It is likely that emphasis will pick up pace, but the legislative rollout will take time and it is more likely to be rolled out in select cities than broadly, especially given the c. 90% homeownership rates in China and the widespread impact that a broad nationwide rollout would have. Rollout in select cities is likely to disproportionately impact luxury goods buyers, but most likely in a limited and gradual manner.

A slow rollout of additional taxes impacting the affordability of luxury goods and the disposable income of luxury goods consumers will act as a marginal, gradual headwind to demand over the next few years, but this is likely to be offset at least as much by a focus on increasing the incomes of potential luxury goods consumers.

Caution on conspicuous consumption as a short-term headwind to demand

The government’s goal of achieving an “olive-shaped” wealth distribution is more focussed on pushing low-income groups into middle-income than shrinking high-income groups. It also seems that the government cares more about how people make their income than preventing them from becoming rich. There is some risk in the short term that wealth accumulated in sectors not aligned with governments objectives may be less inclined to be displayed conspicuously. This headwind is likely to be transitory and replaced by a tailwind from consumption via wealth attained in sectors where the government is encouraging growth.

Growth prospects

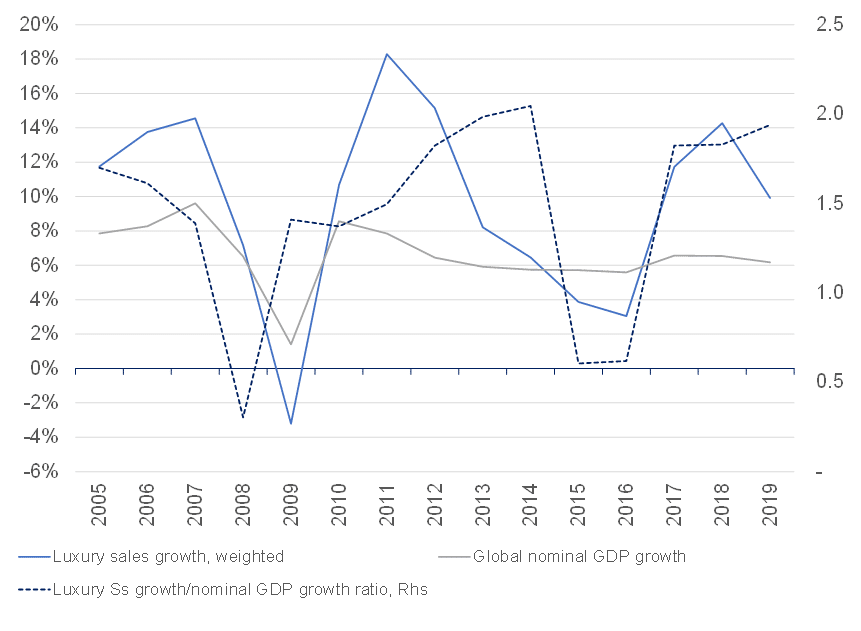

UBS estimates that the >40% of luxury goods purchases are concentrated amongst the few largest luxury goods companies, so we use the sales of the four largest listed luxury goods companies as a proxy for industry trends (LVMH, Richemont, Swatch, and Kering).

Over the past 15 years or so, global nominal GDP growth has gone from about 8% p.a. (4% GDP growth + 4% inflation) to c. 6% p.a. (3% GDP growth + 3% inflation) and the IMF expects it to continue running at c. 6% for the next few years.

Over the past 15 years, sales at the luxury goods majors have run at about 1.6x the rate of global nominal growth (when excluding the global financial crisis [GFC] and the corruption crackdown in China in 2015/2016). We assume that this trend will continue going forward, giving us 8%-10% top-line growth for the industry over the next few years.

Figure 8: Sales of luxury goods have grown much faster than global nominal economic growth for the past fifteen years

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

It is also likely that the trend of soft luxury (e.g., fashion and leather goods) growing slightly quicker than hard luxury (watches and jewellery) will persist. This means we can expect the likes of Hermes, Kering, and LVMH to grow slightly quicker than Richemont and Swatch, especially given the latter’s lack of meaningful soft luxury brands in its sales mix.

Figure 9: LVMH, Hermes and Kering have a higher proportion of soft luxury goods sales relative to Richemont and Swatch, which are predominantly hard luxury companies

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

That said, Richemont’s ventures into the online luxury space will give it exposure to the faster-growing soft luxury segment, albeit at a much lower margin than that enjoyed by the brand owners.

Valuation

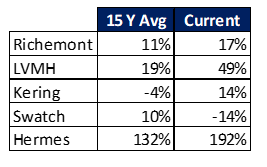

Except for Swatch (which trades roughly in-line with its average forward P/E multiple over the past 15 years), the other luxury goods companies are trading at a significant premium to their historic average.

Figure 10: Luxury goods companies are expensive relative to their own history

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

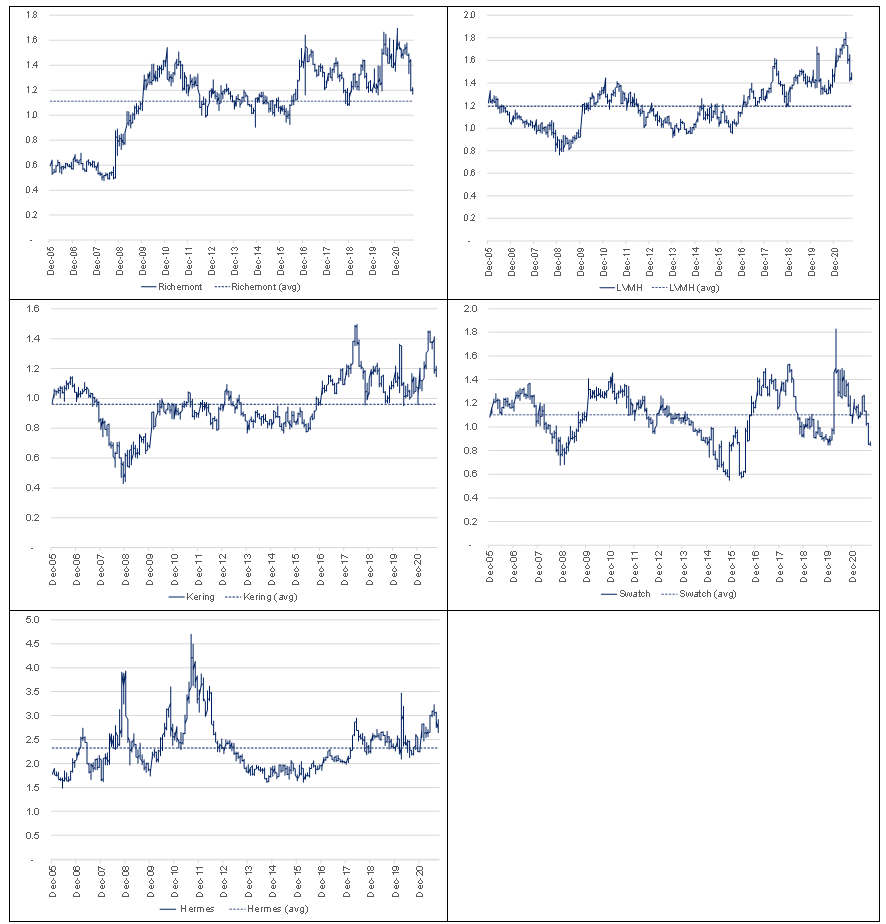

But, with historically low interest rates helping to justify above-average valuations across the market, it is probably more appropriate to compare current valuations to the relative premium that these stocks have traded at historically.

Figure 11: Valuation premium/(discount) that luxury goods stocks trade at relative to the MSCI World

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

And, in that context, we note that:

- The recent regulatory crackdown in China has brought the valuation premium that these luxury goods companies trade at relative to the market, much closer to historic levels.

Figure 12: The recent sell-off in luxury goods companies has brought their valuation premium relative to the MSCI World Index much closer to their historic average premium levels

Source: Anchor, Bloomberg

- The companies skewed towards soft luxury goods (Kering, Hermes, and LVMH) are looking more expensive relative to their own historic premium than the hard luxury goods companies (Richemont and Swatch). This, as investors seem willing to pay up for what appears to be structurally higher margins and the relatively more attractive growth prospects of soft luxury relative to hard luxury.

Conclusion

China’s transition towards “common prosperity” will create some short- to medium-term headwinds to the growth in luxury goods sales, but these should be more than offset by long-term, structural growth in the sector driven by an expanding middle-income cohort in China. The recent sell-off has brought the sector to a level where it trades at a reasonable premium to the market, with soft luxury perhaps looking slightly more expensive than hard luxury. As such, the long-term prospects for the sector remain good, while in the short term the sector is likely to trade largely in line with the market.