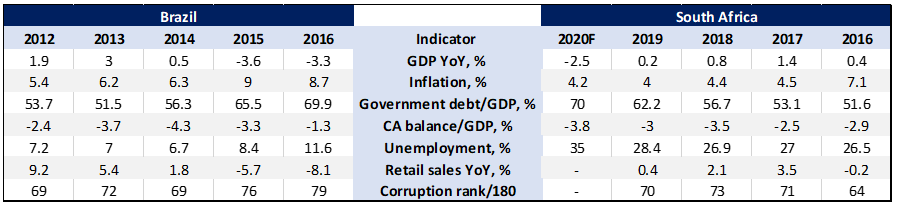

South Africa (SA) lost its final investment grade rating (from Moody’s) on 27 March 2020, in the wake of years of fiscal largesse and low growth compounded by the impact of COVID-19. Brazil lost its final investment grade rating on 24 February 2016, notably also from Moody’s. Brazil’s credit rating downgrade to junk status largely stemmed from economic weakness driven by decreases in the oil price and an inability to reform the government pension fund. Similarly, SA’s downgrade to junk status stemmed from economic weakness driven by poor economic reform and bloated government expenditure (notably the government’s inability to deal with public sector wage growth). Brazil’s downgrade journey rings a remarkably similar bell to that of SA. Pre-downgrade, both countries suffered from extensive corruption, a lack of structural reform, high unemployment, and high fiscal deficits. Indeed, upon closer inspection of some of the key economic indicators for the five years leading to the loss of their final investment grade rating, both countries appear to have followed the same trend:

Figure 1: SA and Brazil’s economic indicators for the 5 years prior to being downgraded to junk status

Source: Moody’s, World Bank, Trading Economics

Given the similarity of both countries’ respective journeys to junk status, it may serve SA well to take a more critical look, not only at Brazil’s economic policies pre-downgrade, but also at its attempt at structural reform thereafter. There may be a valuable lesson to be learned for SA as we take our first tender steps forward through junk status territory.

Trends leading to the downgrade(s): What policy structures were in place?

Since 2010, Brazil’s economic growth slowed significantly – from an annual growth rate of 4.5% (between 2006 and 2010) to 2.1% (between 2011 and 2014). There was a significant contraction in economic activity in 2015 and 2016, with GDP dropping by 3.6% and 3.4% YoY, respectively. This phase of highly depressed economic activity led to a severe recession from 2014 to 2017. By 2016, the country had lost its last investment-grade rating, and it has stayed in junk status territory ever since. The economic crisis was ultimately as a result of falling commodity prices (notably oil) and Brazil’s limited ability to carry out the necessary fiscal reforms at all levels of government, thus undermining consumer, and investor confidence. Furthermore, structural sources of pressure on fiscal spending necessitated a high tax burden (i.e. the bloated government pension system and high unit labour costs stemming from the country’s minimum wage policy). At the same time, unwarranted microeconomic interventions contributed to reduced dynamism and increased financial stress in key sectors. For example, in the energy sector, instead of promoting measures to increase efficiency, government introduced a policy to subsidise electricity prices in 2012, increasing demand despite early signs of a drought and driving electricity companies to borrow in order to cover increased generation costs in the expectation of future government compensation.

Likewise, a high regulatory burden slowed implementation of Brazil’s infrastructure investment programme, especially in its initial phases. Compounding the already significant woes in its key energy sector, Petrobras, the state-controlled oil major also ran into significant trouble of its own. A sustained period of lower oil prices and years of corruption and mismanagement all came to a head. By end-2014, Petrobras’ equity price had fallen by more than 80% in US dollar terms over a 5-year period and its debt levels had increased to the highest in the industry. Brazil’s economic crisis occurred alongside a political crisis that ultimately resulted in the impeachment of then President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, within a haze of various corruption scandals.

All in all, Brazil’s bloated government expenditure; troublesome state-owned enterprises (SOEs); poor policy reform and disjointed regulation in the energy sector as well as years of political corruption and mismanagement sound awfully familiar to the circumstances in SA. With the Moody’s downgrade in March, SA officially joined Brazil in junk status territory, amid widespread fiscal pressures and persistently low growth due to social and political obstacles to reforms. Progress on structural economic reforms has been severely limited since the advent of democracy in 1994, and the role of state capture, mismanagement of SOEs (notably Eskom and SAA), and the inability to cut public wage expenditure during SA’s economic decline has been well documented.

Policy changes as a result of the downgrade

2017 saw the beginning of a slow recovery in Brazil’s economic activity, with YoY GDP growth of 1.1% in 2017 and 2018. The slow economic growth was largely as a result of a weak labour market, investments being deferred by uncertainties about the elections and the truckers’ general strike, which brought economic activities in Brazil to a halt in May 2018. Restoring fiscal sustainability remains the most pressing economic challenge for Brazil. In order to address the country’s unsustainable debt levels, the government has enacted Constitutional Amendment 95/2016, which limits the rise of public spending. This amendment imposes a fiscal adjustment of 4.1% of GDP through 2026 and aims to stabilise debt at about 81.7% of GDP in 2023. Implementing this fiscal adjustment requires reducing the rigidity of public spending and revenue-earmarking mechanisms, which makes more than 90% of the federal government’s primary spending mandatory.

Since assuming office in January 2019, the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly emphasised its commitment to policies and structural reforms that strengthen Brazil’s fiscal accounts, foster macroeconomic stability, and improve competitiveness and productivity throughout the economy. The president and his team have suggested that their reforms will be far-reaching, though details on the much-anticipated social security reform (which is necessary to facilitate complying with the constitutionally mandated spending ceiling) have yet to be officially unveiled. Brazil is still mired in debt, with government debt currently sitting at 91.6%, and projected to increase in the next two years, to 93.9% in 2020 and 94.5% in 2021. Bolsonaro states that the main reason for the country’s persistent debt problem remains the government pension system, as he believes people retire too early with too many benefits. As a result, the senate passed the bill to the much-debated pension reform – the effects of which are yet to be felt. Other policy proposals include a programme of concessions and privatisations, a potential revision of the minimum wage policy, efforts to open the economy, and formal central bank autonomy. Despite high approval ratings since assuming office, Bolsonaro’s administration faces the challenge of passing legislation in a fragmented Congress, which will require astute political negotiations. Fiscal reforms are not popular, and the process of constructing a pro-reform coalition could take time.

Whilst SA has only just begun its journey into junk status, the country is already facing similarly difficult politically centric negotiations – notably with the country’s leading trade unions on cutting public sector wage expenditure and SOE reform. Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic may provide the SA government with a unique opportunity to push through its structural reform agenda, it remains too early to tell if this will indeed be the case. Regardless, it remains imperative that government implements a credible fiscal consolidation plan forthwith, thus leading to a durable (albeit slow) pick-up in growth. Furthermore, a reduction in primary deficits (thus stabilising government debt) remains crucial. Central to achieving either of the latter, is the implementation of much-needed structural reforms for SOEs and the required public sector expenditure cuts.

COVID-19 and beyond

It would be naïve to discount the effect of the global Covid-19 pandemic on Brazil and SA’s respective downgrade recovery plans. For Brazil, growth prospects had looked optimistic at the start of the year, however, intensifying headwinds (mainly from the novel coronavirus outbreak) could have since derailed its momentum. The pandemic’s impact on the global economy, commodity markets, and global financial conditions appear set to curtail Brazilian economic activity in 1H20, particularly in manufacturing, tourism, and trade. Moreover, the virus’ emergence in Brazil raises concerns that a full-on outbreak could cause the reform agenda to take a backseat. As of 16 April, in order to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, the Brazilian authorities announced a series of fiscal measures amounting to 6.5% of GDP – about half of which will have a direct impact on the 2020 primary deficit. With Congress declaring a state of “public calamity” on 20 March, the government’s obligation to comply with the primary balance target in 2020 has since been lifted.

The government has also invoked the escape clause of the constitutional expenditure ceiling to accommodate heightened healthcare spending and broader social assistance. The fiscal measures include temporary income support to vulnerable households; cash transfers to informal and unemployed workers; advance payments of salary bonuses to low-income workers; employment support (partial compensation to workers who are temporarily suspended or have a cut in working hours) as well as temporary tax breaks and credit lines for firms that preserve employment; lower taxes and import levies on essential medical supplies; and new transfers from the federal to state governments to support higher health spending and act as a cushion against the expected fall in revenues. Furthermore, public banks are expanding credit lines for businesses and households, and the government will back a 0.5% of GDP credit line to cover payroll costs.

For SA, the immediate sharp downturn in 2020 (led by the pandemic) was – so to speak- the final nail in the coffin for the country’s hold on its last investment grade rating. In response, the SA government placed the country under a strict 21-day lockdown, which was later extended until the end of April. On 21 April, President Cyril Ramaphosa unveiled a R500bn ($26bn) package to boost the country’s ailing economy and to support those who’ve been worst affected by the pandemic. The plan will be funded by reprioritising R130bn of expenditure from existing budgets and borrowing from both domestic and international lenders. Of the R500bn, R200bn will be allocated as guarantees for banks to encourage them to lend; R100bn will go towards job protection, R130bn will be allocated to social protection measures (primarily in the form of increased welfare grants) and COVID-19 specific measures, while the remaining R70bn will take the form of tax deferrals. The stimulus package is the latest in a string of measures implemented by the SA government, with assistance already being provided to those companies and workers facing distress through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and special programmes from the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

Funds are also available to assist small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) under stress, mainly in the tourism and hospitality sectors, and small-scale farmers operating in the poultry, livestock, and vegetables sectors. In addition, with the assistance of private contributions, allocations are being made to a Solidarity Fund to help combat the spread of the virus. The SA Revenue Service (SARS) is accelerating reimbursements and tax credits, allowing SMEs to defer certain tax liabilities, and it has also issued a list of essential goods for a full rebate of customs duty and import VAT exemption. Given the highly fluid nature of the current global economic situation, only time will tell as to the impact the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the economies of Brazil and SA, and thus the trajectory which their respective recovery plans will have thereafter.

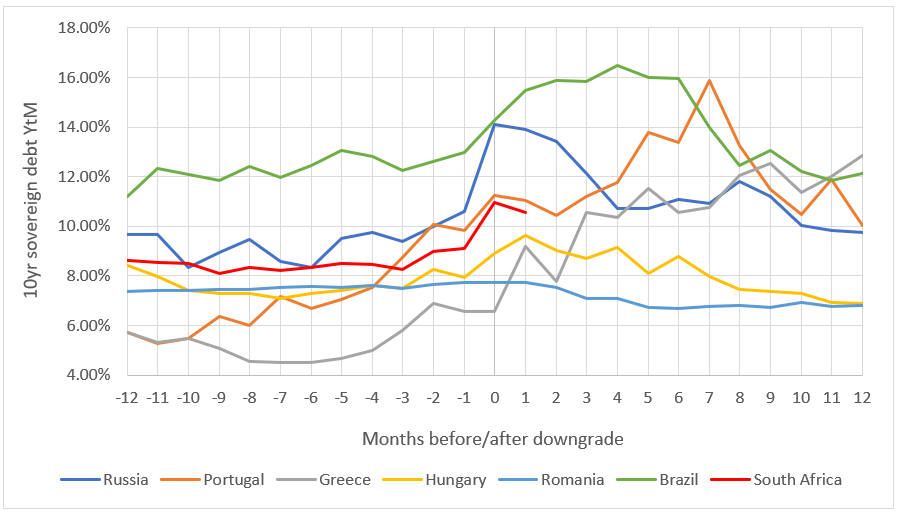

Below, we trace the evolution of several countries in the lead-up to, and post, the loss of their last investment grade rating (note SA [in red] has only one “post” data point):

Figure 2: Downgrade comparison (on 10-year government domestic-denominated debt) of 12 months pre- and post-downgrades on sovereign debt

Source: Thomson Reuters

As per Figure 2 above, Brazil’s 10-year debt peaked at over 16%, while SA 10-year debt has only recently gone over 10%. The peak-to-trough difference is around 4% for Brazil and around 3% for SA. This implies more of SA’s weakness was already priced in within the 12 months prior to the final downgrade (we note that this ties into the view that the SA downgrade had been priced-in for some time).

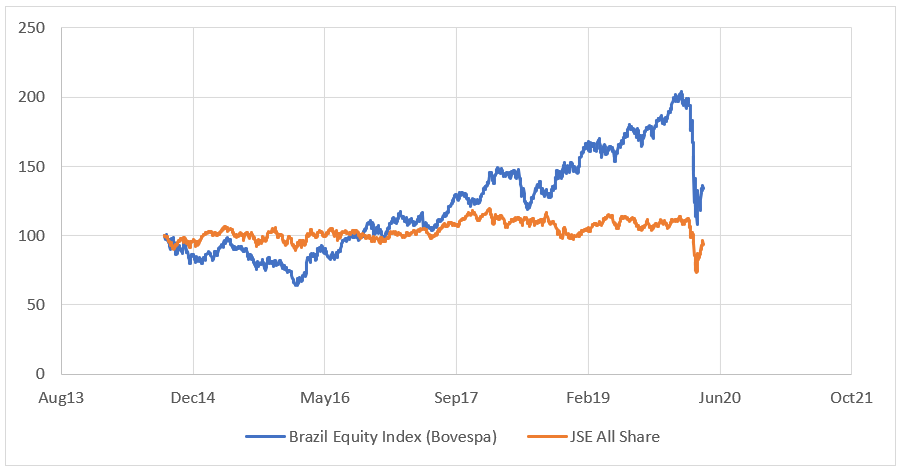

We further highlight the Brazilian Bovespa (equity) Index as compared to the SA FTSE JSE All Share Index (ALSI) over the past 5.5 years:

Figure 3: Brazil vs SA’s main equity indices (rebased to 100 as at end-September 2014)

Source: Thomson Reuters

Both above indices show the recent impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we further highlight the weakness of late-2015/early-2016, likely driven by the Brazil downgrade and recession. The SA ALSI has largely moved sideways since late 2014, with a near-0 return for investors, and marked losses on account of COVID-19 in the past two months.

In the near term, we think that local bonds should recover their lost value. Unfortunately, longer term, we note that structural reform will be required to return SA to a growth-positive and fiscally neutral path. Current estimates are for deficits in 2020 of over 10% (vs an expectation in February when the budget was delivered of 6.8%). This will have to be addressed, lest we are faced with a spiralling debt trap.