1. What is asset allocation

Investors are universally aligned in the objective of growing their investments as much as possible, but that is usually where the alignment ends. They are often at odds as to from where the best potential for capital growth will likely come. Investors are also rarely in agreement as to how much they are willing to see the short-term value of their capital fluctuate (or more pertinently, drop), in order to achieve long-term capital growth.

That is where asset allocation comes in. At its most basic level, asset allocation involves creating an investment portfolio with investments spread across various:

- Companies,

- sectors and styles,

- regions, and

- asset classes

Metaphorically, this means investors placing their investment eggs into different baskets to mitigate against unexpected outcomes in any single investment. To put it simply, it means diversifying potential risks in the process of constructing an appropriate investment portfolio.

2. How do we go about allocating assets?

Investors, being human, run a broad gambit of risk tolerances, so, constructing an appropriate investment portfolio can be a very personal task, but the techniques used for achieving an appropriate portfolio can be broadly split into two main categories:

Accessing different sources of economic and earnings growth.

Investing across different companies, sectors, styles and regions is a way of ensuring that investments are not overly exposed to drivers that could unexpectedly be derailed by events which are often difficult to predict such as regulatory changes, natural disasters, disruption or fraud. An event such as the current COVID-19 crisis is a great example of where well-managed companies have been forced to their knees by events beyond their control or most investors’ ability to foresee (e.g. premier global online travel agent, Booking.com has lost a quarter of its market value since the start of the pandemic and, in SA, a business like Sorbet could see up to 40% of its 220 salons across SA closing permanently).

This form of diversification is achieved primarily through bottom-up stock selection, finding companies in different industries, with earnings in different regions, that are unlikely to be linked by the same source of disruption.

Adding different asset classes that are less susceptible to capital losses in the short term.

This part of portfolio construction, by and large, involves adding some level of portfolio insurance. Much like regular insurance there is an ongoing cost involved (in the case of your portfolio it is more of an opportunity cost – forgoing some potential growth) to protect against a potential future loss, which may or may not happen.

The primary asset classes we consider when adding “insurance” to our portfolios are:

Assets whose capital is guaranteed:

a) Cash is typically the safest investment (and the most liquid), particularly when held in a regulated financial institution where the government guarantees deposits. Holding cash though typically guarantees negative real (above inflation) growth after fees and taxes, so it has arguably the highest opportunity cost of all portfolio insurance.

b) Structured products, with an embedded capital guarantee. Structured products usually only offer capital protection at expiry, which is often after several years. So, investors adding portfolio insurance in order to guarantee that they will be able to access liquidity in their portfolio at any time, without worrying about locking-in large capital losses should liquidity be required during a market correction, should bear in mind that structured products may not be well suited to fulfil that role in their portfolio.

Assets that typically appreciate when growth-sensitive assets depreciate:

a) Bonds; and

b) gold

Each of these asset classes have various characteristics that make them attractive from a portfolio insurance perspective, but they all come with unique “costs” to the portfolio and may provide imperfect protection when you need them most.

3. Potential pitfalls of asset allocation

The illusion of diversification

Same theme applied in multiple different ways:

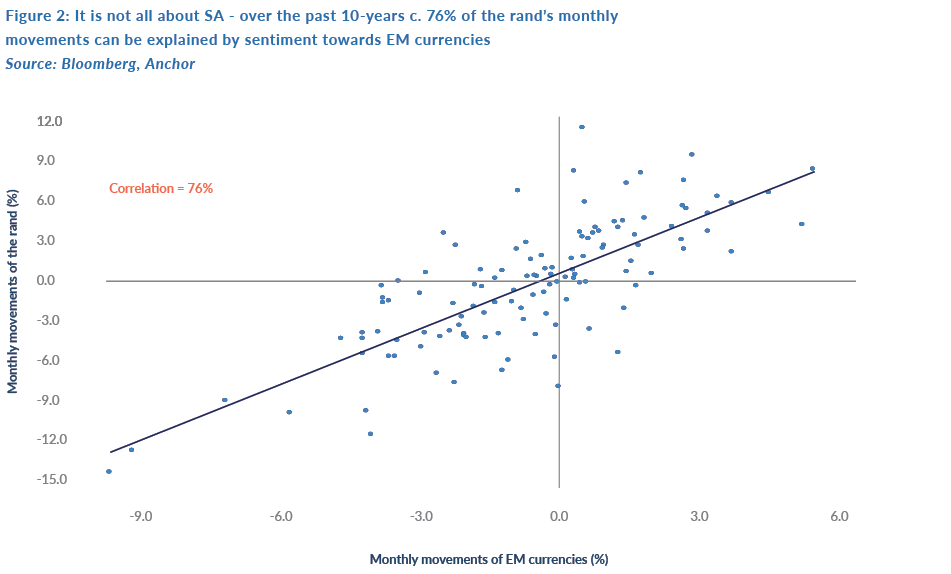

This is essentially like having lots of different eggs but keeping them all in the same basket. SA investors are particularly susceptible to this. We are faced daily with the challenges that many EM citizens are forced to live with including corruption, high levels of unemployment, poor governance, and sub-standard basic services, so it is easy to become disillusioned about the local economy. This sentiment can then become pervasive in investors’ asset allocation as they maximise their allocation to global investments and favour local companies’ shares, which earn some or all of their income outside of SA. This is a perfectly acceptable approach for many investors, but it does make their domestic currency returns extremely susceptible to the local exchange rate, which is extremely volatile and is also, in the short- to medium-term, influenced to a large extent by non-SA factors such as sentiment towards EMs or the value of the US dollar relative to its DM peers.

Different themes all linked by a higher-order effect.

a) Liquidity is often a key theme linking seemingly uncorrelated investments in times of crisis. Investors all needing to raise cash at the same time flood the market with supply just as demand dries up. This is most extreme in less liquid investments that even during the good times have limited demand.

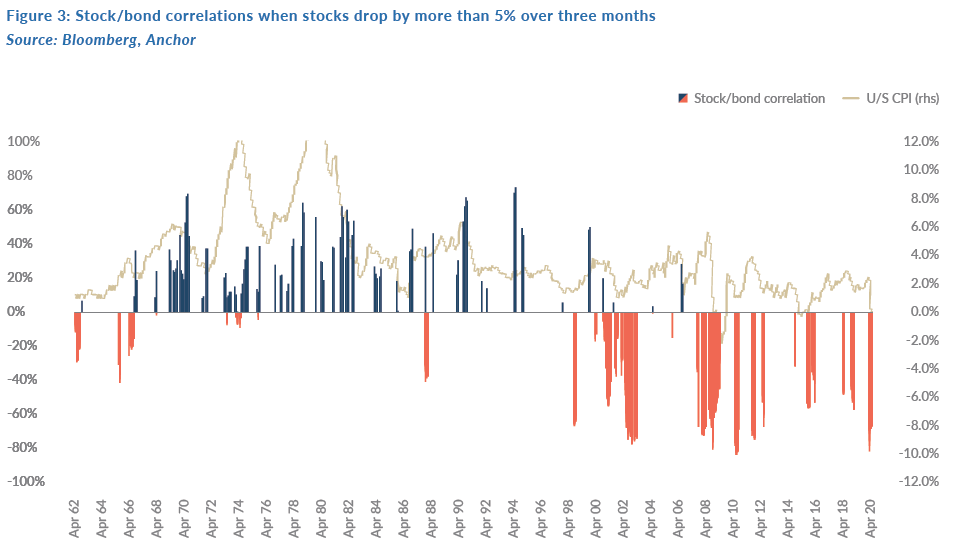

b) Inflation, or more specifically inflation volatility, is another factor that is often linked to the performance of stocks and bonds. Before the US Fed started specifically targeting inflation (and getting it under control), predominantly this century, high and volatile US inflation (which tends to be negative for both stocks and bonds) would usually result in bonds falling at the same time as stocks.

The illusion of capital protection

The worst-case scenario for investors is when they have decided to forgo some of their long-term growth potential to protect capital in the short term and the insurance does not work when they need it to. This is often the case when investors are reluctant to give up too much for their insurance.

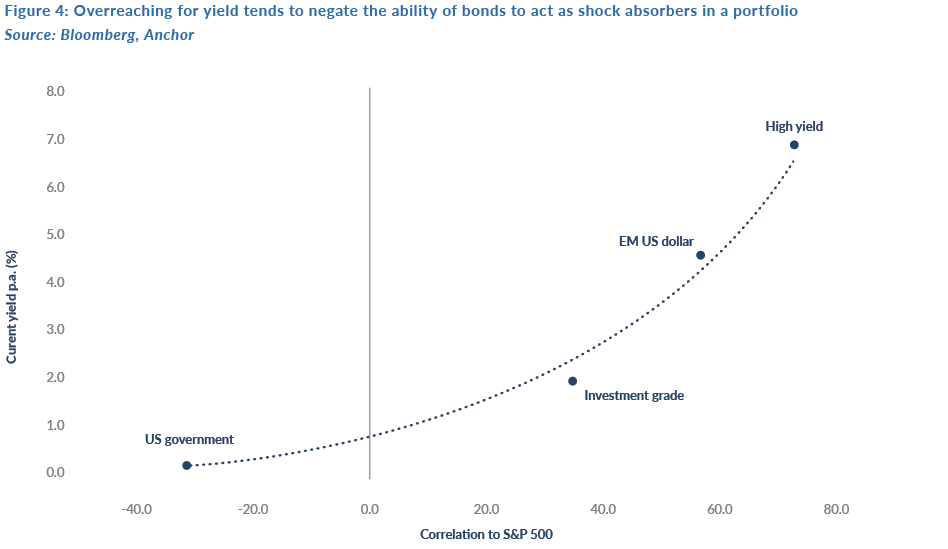

Bonds

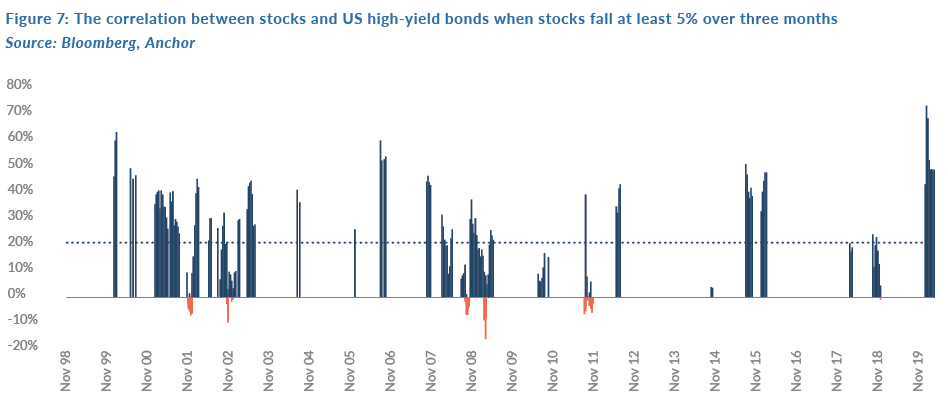

While DM bonds have certainly worked well as short-term hedges against falling stock markets for the past 20 years or so, the opportunity cost of holding bonds has continued to rise as low inflation and aggressive quantitative easing (QE) has squeezed real bond yields to unattractive levels, limiting their long-term return prospects. Enter the search for yield as investors try and reduce the opportunity cost of insurance – unfortunately, as with many things in life, cheaper is not always better as the higher the credit spread embedded in bonds, the more likely they are to move in synch with equities.

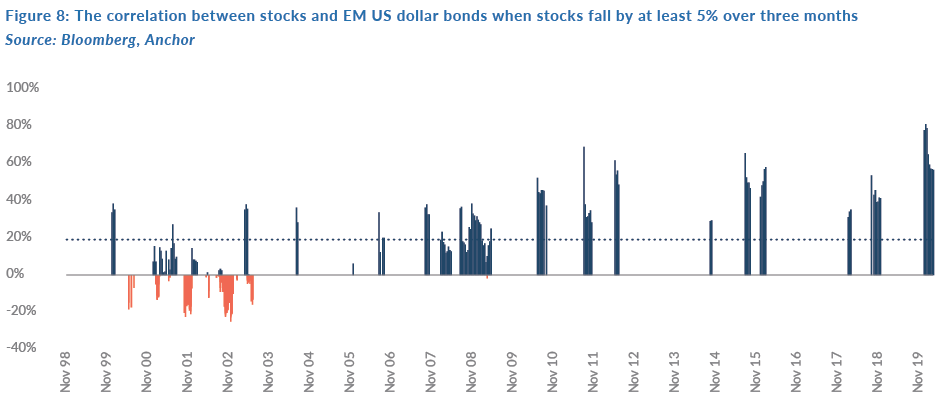

So, investors adding bonds to a portfolio in the hope of achieving some insurance, tend to do themselves a disservice in their overreach for yield. This is particularly true when the insurance is needed most i.e. when equities experience short-term drawdowns.

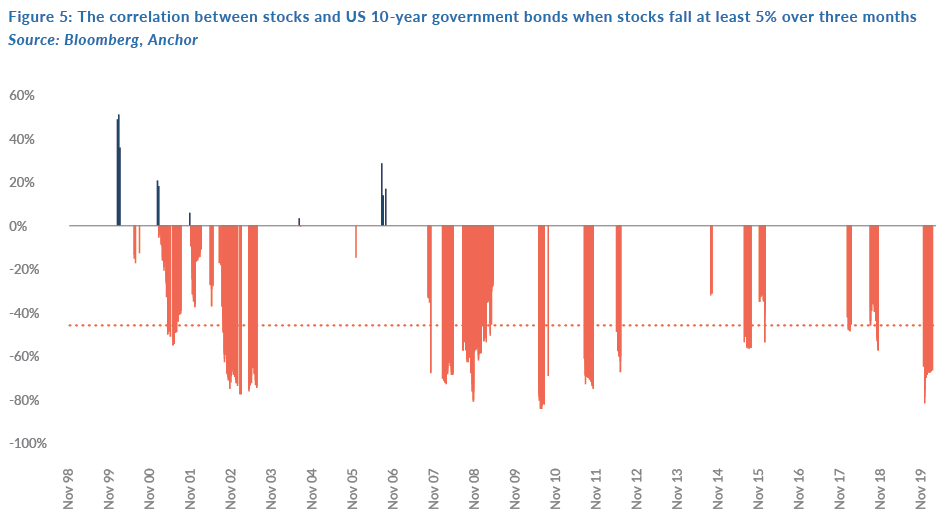

When equities fall by 5% or more over three months, US 10-year government bonds move strongly in the opposite direction (i.e. up):

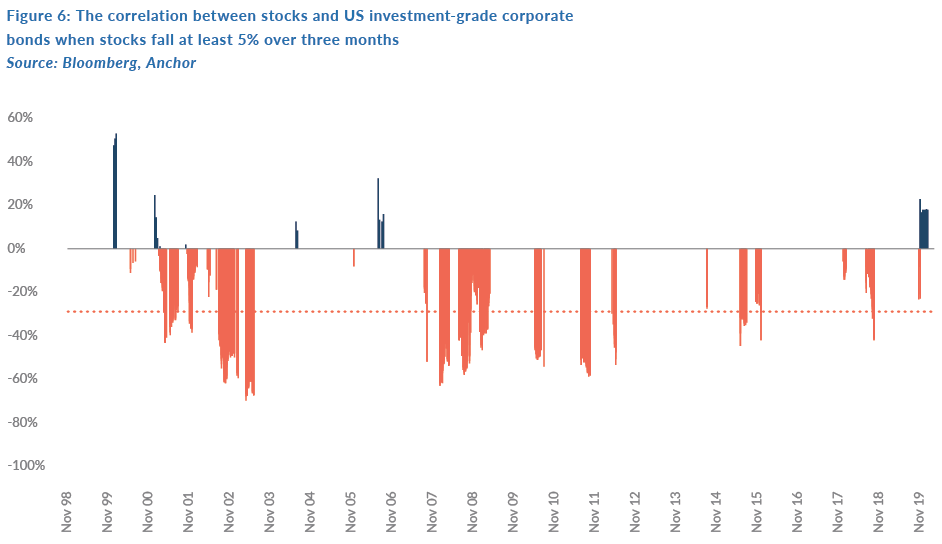

US investment grade credit moved somewhat in the other direction (i.e. moderately up):

Over the past 20-odd years, the major exception to this was the sell-off in March this year when investors initially panicked that the corporate bond market might seize up (in the wake of the GFC, regulators made it much harder for banks to provide liquidity to corporate bond markets). Fortunately, the Fed stepped in to allay those fears with a corporate bond purchasing programme of its own.

When it comes to high yield bonds the chances of them losing money, when you have a short-term correction in equity markets, is reasonably high. Just because they are called bonds does not mean they are going up (or at least not going down) when equity prices fall.

The same goes for high-yielding US dollar bonds issued by EM issuers.

Gold

Gold is a popular hedge against uncertainty in investors’ portfolios and a complicated one to understand. Victorian Europe’s richest man, and bullion broker to the Bank of England, N.M. Rothschild said: “I know of only two men who really understand the value of gold, an obscure clerk in the basement vault of the Banque de France and one of the directors of the Bank of England. Unfortunately, they disagree.”

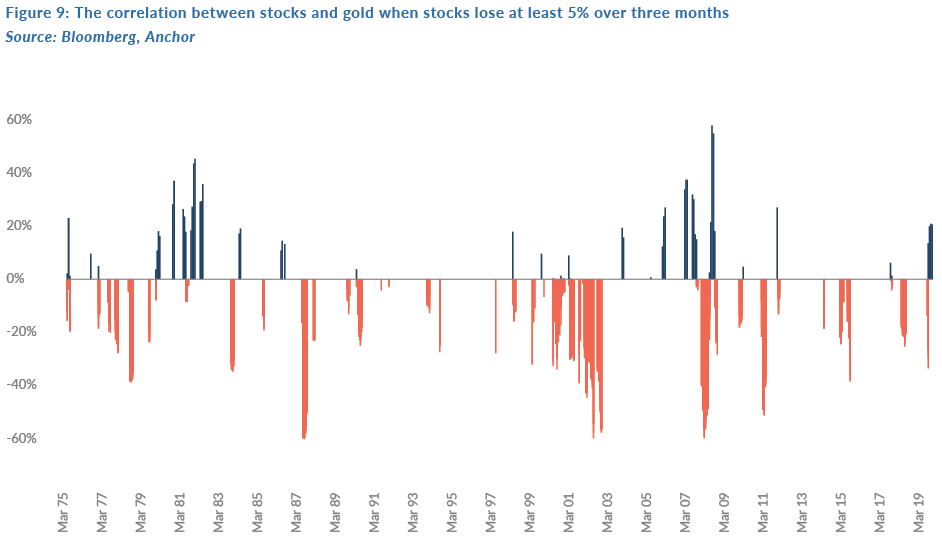

We include gold in portfolios primarily because we expect it to appreciate when the value of our stocks goes down in the short term, and so we look at how it moves when equities drop. For the past c. 50 years it has been about 75% effective – i.e. three out of four times when stocks fell by more than 5% over a three-month period, gold rallied. This compares to government bonds, which were effective only 63% of the time, although this increased to 98% over the past 20 years, when inflation has been largely under control.

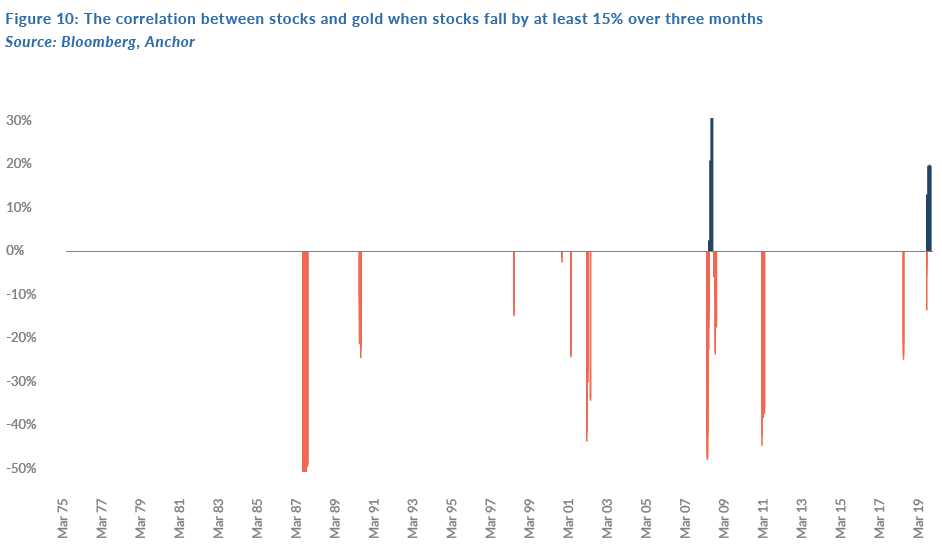

We also looked at how gold did with more meaningful stock market collapses – to see if it perhaps fared better during bigger stock market corrections – when stocks dropped more than 15% over the course of three months. The results were reasonably similar – gold was an effective hedge about 77% of the time. Perhaps what was more worrying was that the times it did not really work well (when gold fell alongside equities), were during the two most recent crisis – the GFC and, recently, during the COVID-19 crisis.

Conclusion

Constructing an appropriate investment portfolio is typically a very personal exercise, weighing investors’ risk appetite and liquidity requirements. Stock selection can help in the process of accessing a variety of long-term growth sources, which can help investors diversify the risk inherent in specific economies or sectors and, hopefully, reduce the impact of less predictable outcomes like regulatory changes, fraud or natural disasters.

Investors can add other asset classes that offer some form of short-term insurance either because of explicit or intrinsic capital protection or from the nature of the asset classes, which results in them rallying when risk assets are falling. There is a cost associated with adding portfolio insurance in the form of other asset classes – this is predominantly an opportunity cost of forgoing future potential growth. It’s important for investors to remember that they may negate the short-term insurance that they desire in an attempt to reduce this opportunity cost by trying to achieve too much yield in their bond allocation or by choosing assets, such as gold, which have historically only rallied as equities fell about 75% of the time.