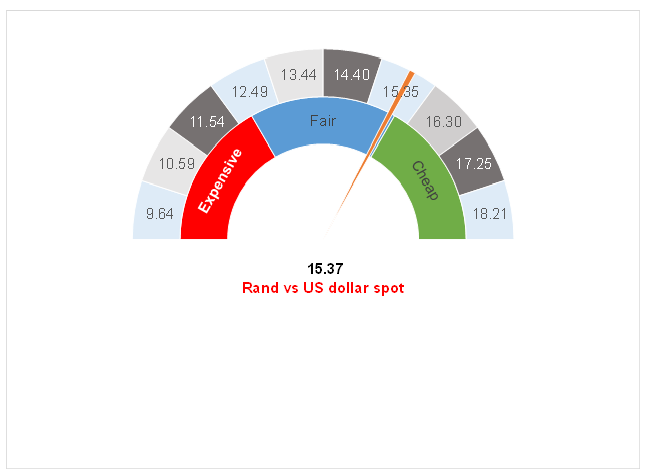

Figure 1: Rand vs US dollar

Source: Anchor

On Friday (20 November), Moody’s downgraded South Africa (SA) to Ba2 (with a negative outlook), while Fitch Ratings downgraded the country to a BB- (also with a negative outlook). Standard & Poor’s was the only rating agency not to downgrade SA, retaining its BB- rating for foreign currency debt (with a stable outlook). These downgrades surprised many economists and market participants. From a financial market perspective, there are certain downgrades that matter a great deal and certain downgrades that are rather more academic in terms of their impact. Fortunately, these latest downgrades would fall into the latter category and the rand vs US dollar exchange rate is slightly firmer on Monday morning (23 November), whilst bonds have wobbled around a bit, but effectively are unchanged in value and in yield. However, from a SA psyche perspective, these downgrades are once again a reinforcement of the price that has to be paid for having one of the most stringent lockdowns in the world. Public debt will soar to over 95% of GDP in the near term and that number assumes that the government is able to achieve all it has promised in terms of expenditure cuts and growing the economy. In recent years, government has had a particularly poor track record on both of these fronts which, in part, is the reason why it is battling for credibility with rating agencies and investors alike. SA’s debt is out of control and the politically easy solutions are no longer viable.

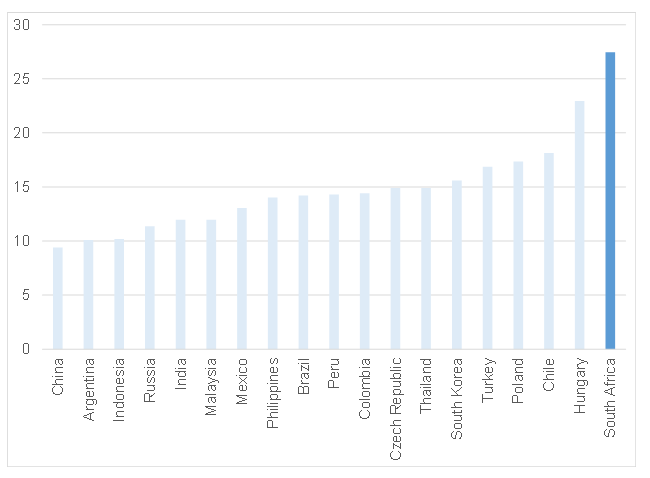

SA is already very highly taxed compared to its peers, arguably even overtaxed (see Figure 2 below, which compares SA’s tax revenue as percentage of GDP with its peers). This also indicates that there is very little scope for government to raise further revenue through taxes in order to address the country’s debt burden.

Figure 2: Government tax revenue as percentage of GDP

Source: World Bank

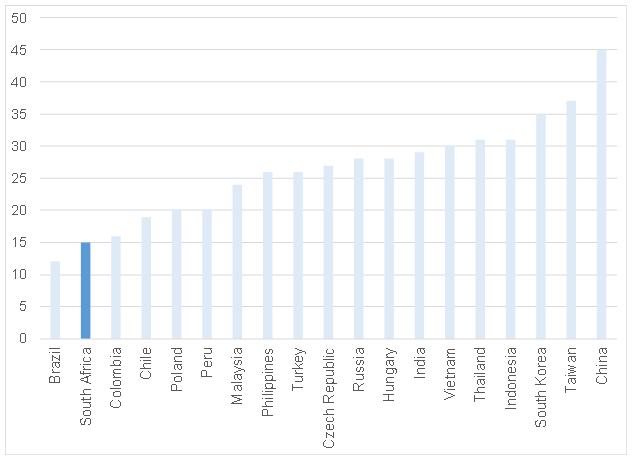

Another issue which the SA government faces is that our domestic bond market is not infinite. In fact, SA has one of the lowest savings rates in the world (see Figure 3). This means that domestic savings can only go so far in terms of funding our government and that the government will soon crowd-out other borrowers in the market. In short, SA cannot in the long run depend only on domestic savings to fund itself and the country will need to maintain its access to international markets. Government’s credit ratings are very important for it to maintain its access to these international finance markets, at a reasonable price.

Figure 3: Savings rate as a percentage of GDP

Source: World Bank

For now, SA is able to finance itself from domestic markets, however, the longer the government takes to bring its finances under control, the more government’s domestic borrowing needs will smother the private economy. Thus, all eyes are on the government wage negotiations as government does not have any alternative levers it can use to reduce the pressure on the country’s finances.

The rating agencies are aware of this pressure (and the market has already priced in its skepticism of government’s ability to deliver). Hence, while Friday’s downgrades are a stark reminder of the fiscal cliff the country faces, market reaction to these downgrades will remain muted. If government fails on its wage negotiations, then we expect further (and harsher) downgrades to come swiftly. For now, however, the market has adequately priced in this risk and is looking abroad for its cues.

Market commentators abroad have also been calling for a weak US dollar for the past three years. Sometimes, these commentators are more muted and sometimes they are more emphatic in their calls. However, we have seen very little US dollar weakness over the past three-year period, and far less than market commentators have been suggesting. These commentators have now seen Democratic Party candidate Joe Biden’s victory in the US Presidential Election as an opportunity to become quite emphatic about their call for a weaker dollar. We believe that this is largely premised on US fiscal stimulus increasing the fiscal risks and weighing on the attractiveness of the US as an investment destination. Arguably, should Biden start to pursue his tax hikes strategy, this could also detract from the strength of the US dollar. We believe that there is some truth to these risks and that one cannot discount future dollar weakness. However, we are also of the view that any US dollar weakness is likely to be relatively modest and we believe that weakness of between 5% and 10% against a basket of currencies would be the upper range of our forecast. More importantly, we note that while the risks of dollar strength persist, the global backdrop for SA will be supportive of a slightly stronger rand.

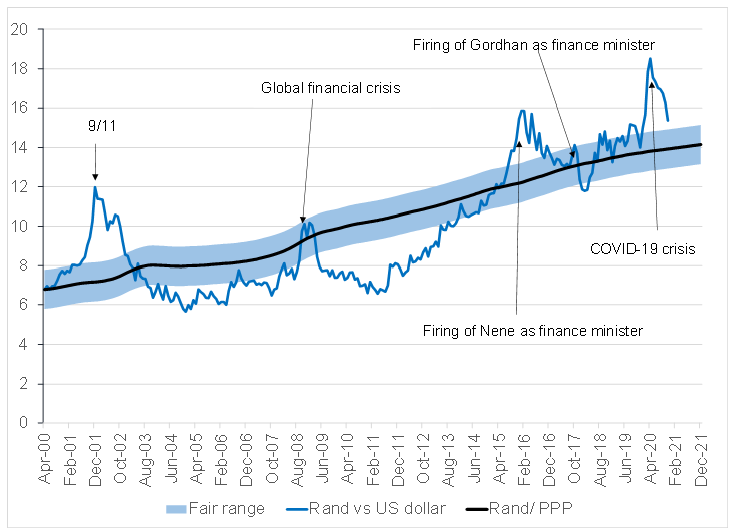

On Monday morning (23 November) the rand was trading at c. R15.37/US$1. We think that the local currency could reasonably end this year somewhat stronger vs the US dollar as global forces maintain this slight strengthening bias. The improved terms of trades for SA, due to a weaker oil price, is also rand-supportive in the near term and we see that the rand has now strengthened to the cusp of our fair-range forecast. We expect that further rand strength from here will likely be gradual and slower. We also think that current trends can carry the local unit further into our target range, although we note that the local unit will likely remain on the weaker side of fair. We are neutrally positioned on the US dollar at the moment and we will probably look to increase our exposure to the greenback should the rand move into the high-R14s against the dollar. We do caution that the short-term behaviour of the rand is random and that our views of a continued rand recovery do not have the strength of conviction that we had only a few months ago.

Figure 4: Actual rand/$ vs rand PPP model

Source: Bloomberg, Anchor