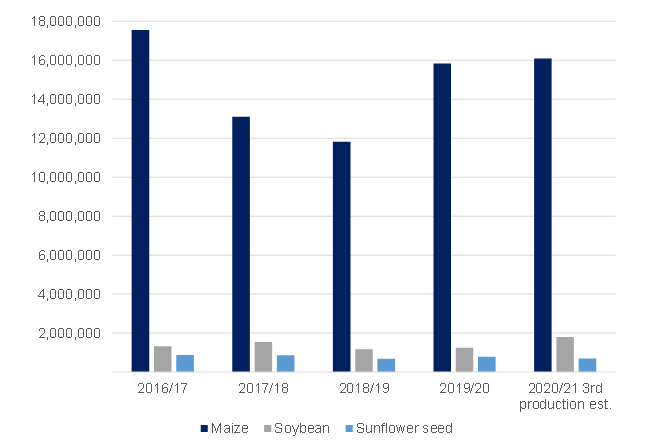

At the end of April, the South African (SA) Crop Estimates Committee (CEC) released its forecast for the 2020/2021 summer crop season. The CEC’s April 2021 forecast (i.e., the third production forecast for the year) points to 16.1mn tonnes for maize (up 5% YoY, and the second-largest harvest on record), 1.8mn tonnes for soybeans (up 44% YoY, a record harvest), and 189,885 tonnes for sorghum (up 20% YoY). Meanwhile, sunflower seed and groundnut production estimates were unchanged from March 2021, at 696,290 tonnes (down 12% YoY) and 57,900 tonnes (up 16% YoY), respectively. Dry beans were the only crop, which saw estimates slashed by 9% MoM to 56,577 tonnes (down 13% YoY).

Interestingly, both the Agricultural Business Chamber (Agbiz) and the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy believe that maize production could trend even higher in the coming months, forecasting that SA’s maize production could reach 16.7mn and 17mn tonnes, respectively. Nonetheless, current maize production data essentially indicate that SA will remain a net exporter in the 2021/2022 marketing year, starting this month (May 2021, which corresponds with the 2020/2021 production season).

Figure 1: SA’s key summer crop production, tonnes

Source: CEC, Anchor

SA’s maize consumption averages around 11.4mn tonnes p.a., thus there will likely be over 2.8mn tonnes of maize available for export markets – all else being equal. Once harvesting gains momentum, the expected large harvest could add downward pressure on domestic maize prices but likely only at a marginal rate as the higher global maize market remains supportive of domestic prices. Strong maize demand from China, rising concerns for Brazil’s maize crops due to drought, very dry soils in Canada (where planting is about to start), as well as dryness in parts of the US are some of the key factors driving this increase in global maize prices, which are now at their highest levels since 2013.

Over the past few months, the weaker rand in 1Q21 ,growing demand for SA maize in the Southern Africa region and the Far East, coupled with generally higher global grain prices, have provided support to domestic maize prices. However, Southern Africa’s demand will likely soften this season as the region is expecting a large harvest across all major maize consuming countries. The domestic currency has also firmed of late. The only major upside driver of domestic maize prices is the rally in global maize prices, regardless of large domestic supplies. With regard to soybeans, price dynamics are typically similar to that of maize. Nonetheless, the forecast increase in the soybean harvest will have a minimal effect as SA remains a net importer of soybean meal (although volume will fall notably this year on the back of the large domestic harvest from the usual 500,000 tonnes p.a. in imports). Hence, global soybean market dynamics will continue to influence local prices.

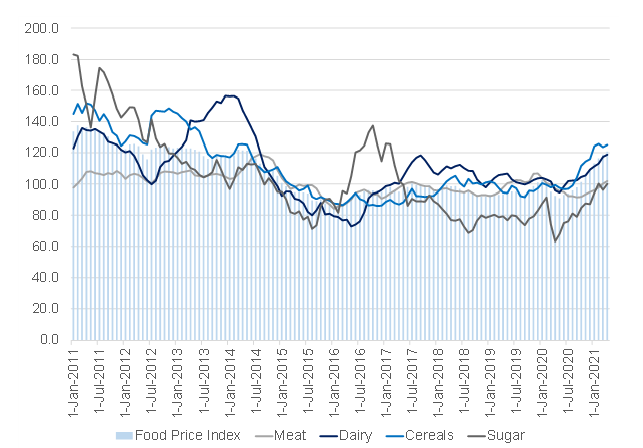

Globally, agricultural commodity prices remain elevated, as illustrated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ (FAO’s) April 2021 Global Food Price Index results, which were up by 2% MoM and 31% YoY – currently measured at 121 points. This is the eleventh-consecutive monthly rise, and the index is now at its highest level since May 2014 (see Figure 2). The gain was underpinned by the increase in all sub-indices including sugar, vegetable oils, meat, dairy, and grains. The smaller-than-anticipated US grains planting intentions, coupled with rising concerns about crop conditions in that country (as illustrated by slower maize plantings on the back of dryness), have added upward pressure on prices. In addition, firm Chinese maize demand, rising concerns for Brazil’s maize crops due to drought, the very dry soils in Canada, where planting is about to start, are further driving the increase in global grains prices.

With regards to vegetable oilseeds, increasing soybean demand from China, combined with the slower-than-expected production growth of palm oil in major exporting countries have supported prices these past couple of months. The stronger Chinese demand is also the main driver of an increase in global dairy prices. Meat prices are also being supported by strong demand from East Asia, with China currently experiencing other outbreaks of African swine fever. Similarly with sugar, the drought in Brazil and the frost in France are primary factors currently supporting prices. It is important to note these global agricultural commodity factors when considering local commodity trends, especially given their influence on both domestic commodity prices and on those commodities of which SA is a net importer, such as vegetable oils and grains (wheat and rice).

Figure 2: The FAO Global Food Price Index performance

Source: FAO, Anchor

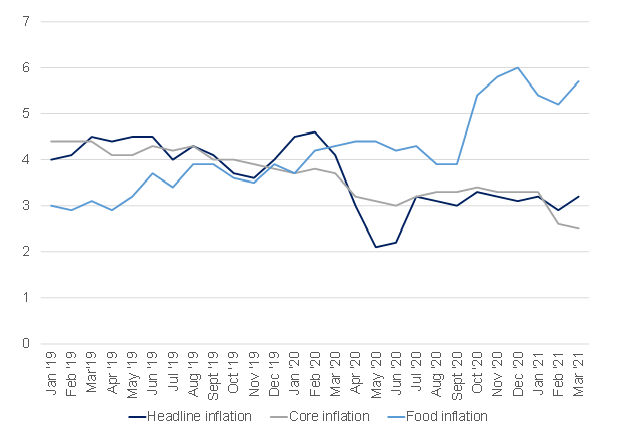

Looking at domestic price trends in particular, SA consumer food price inflation rose marginally in March 2021 to 5.9% YoY vs 5.4% YoY in February. The product prices underpinning the uptick were mainly bread and cereals, fish, milk, eggs, and cheese, and oils and fats. The increase in the prices of these products is not surprising to us and reflects the elevated farm-level prices observed at the end of 2020 and into 2021. Typically, the passthrough from the farm level to the retail level for products such as grains is three months. While SA’s consumer food price inflation was generally elevated in 1Q21, expectations are for it to soften from 2Q21. This will be primarily underpinned by grain-related products, whose prices could soften and filter through, with a lag, on the “bread and cereals” products’ prices. The anticipated decline in prices is on the back of the large forecast harvest of 16.7mn tonnes. This product category also has a higher weighting of 21% in the CPI food basket, and changes in its price inflation will be noticeable.

In terms of meat prices, Agbiz forecasts a sideways price movement for the coming months. It believes that cattle slaughtering could slightly improve in 2021, and the base effects on poultry meat, which increased in 2020 partly because of an import tariff hike, could bode well for food price inflation. As SA is a net importer of vegetable oils, the prices also tend to be influenced by the exchange rate. Thus, the relatively firmer current rand vs US dollar exchange rate bodes well for oils and fats price inflation over the coming months. The key upside risk to SA’s current food price inflation remains rising fuel prices. SA’s agricultural commodities and processed food are primarily transported by road, and increased transport costs could impact the final product prices. For example, SA is transporting c. 81% of maize, 76% of wheat, and 69% of soybeans. On average, 75% of national grains and oilseeds are transported by road. However, higher food prices are not typically fully passed on to consumers, as other factors (such as operational efficiencies and a preference to retain market share) typically have a greater impact.

Figure 3: SA YoY inflation rates, %

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

Ultimately, the initial 2021/2022 global grains and oilseeds production forecasts paint a slightly more positive picture than many had feared. If more on-the-ground evidence emerges to support these global forecasts then, over the coming months, global agricultural prices could potentially moderate from their current high levels (as illustrated in Figure 2). This, along with the strong projected summer crop harvest in SA, would in turn assist in keeping local food inflation relatively muted.