I have followed the cybersecurity sector as an analyst for over 15 years and I have always found it to be a fascinating industry. Cybersecurity has remained mission-critical for corporates (and private individuals) of any size for many years. The industry’s mission to protect digital and physical assets has become increasingly critical every year. In recent years, it has also become more widely followed by financial market commentators and participants. However, the core thesis behind investing in the sector is unchanged, and at Anchor, we have a long-term positive view around investing in global cybersecurity. We believe it is a sector with long-term secular tailwinds, offering a promising investment thesis.

While it may be tempting to fill many pages with a deep dive into the intricate inner workings of the cybersecurity industry, this review is intended to be a high-level summary. Once you drill down below the surface, the industry becomes highly complex and even seasoned tech experts are left floundering at the complexity beyond a certain point.

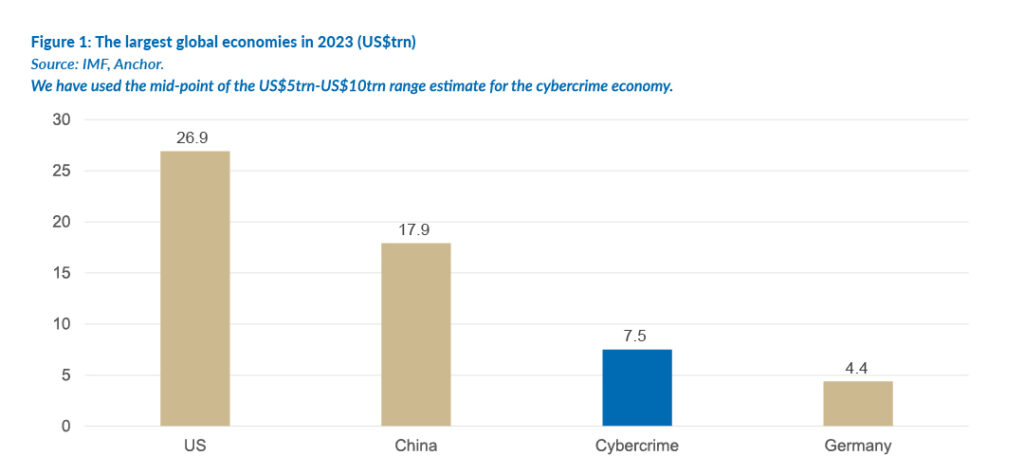

The estimates of cybercrime’s costs to the global economy vary widely, ranging between US$5trn and US$10trn p.a. Either way, the cost is enormous. This has led many observers to rank cybercrime as the third-largest “economy” in the world after the US and China.

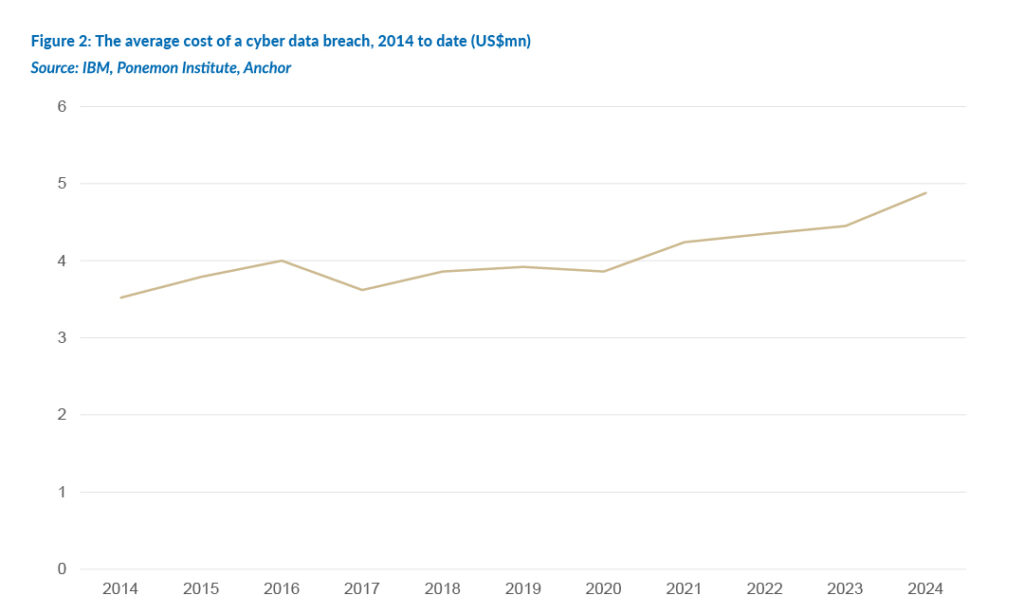

The average cost to corporates of a data breach has steadily risen to US$4.9mn by 2024, according to research done by IBM and the Ponemon Institute. A breach can be traumatic for any organisation. The costs of a data breach include the costs of detecting the breach, post-breach remediation, and the subsequent loss of business. It seems inevitable that most corporates will, in time, experience a breach of some sort. The aim is to try and keep the frequency and the impact of data breaches to an absolute minimum. None of the cybersecurity companies can claim that their offerings are 100% foolproof. Although there are many initial attack vectors, compromised credentials top the rankings. A corporate can have the best cybersecurity systems in the world, but the entire organisation is at risk if an employee is careless with their login credentials.

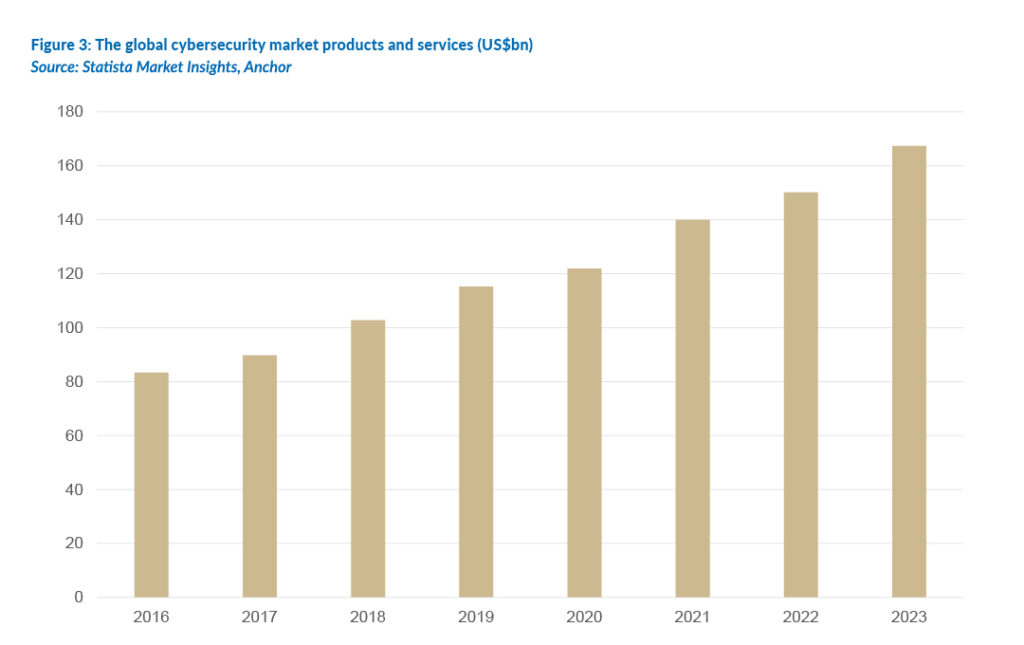

The global cybersecurity market, including all products and services, was valued at an estimated US$167bn in 2023 and will reach nearly US$300bn by about 2032. This is a significant revenue pool that cybersecurity companies are competing over.

There is an interesting analogy between investing in the cybersecurity and defence industries. The defence industry offers many attractive properties, such as mission-critical and resilient demand throughout the economic cycle. However, many potential investors baulk at the “killing” aspect that goes with the defence industry. The cybersecurity industry offers many qualities similar to those of the defence industry but without negatively impacting human lives. Many of the world’s leading cybersecurity companies sell to governments even though it is a relatively small part of their total earnings.

Morgan Stanley publishes a quarterly survey of US corporate chief information officers’ (CIOs) tech budgets and spending trends. These surveys typically show cybersecurity spending as the part of IT budgets that are least likely to be cut. While the cybersecurity industry is not entirely immune to broad economic downturns, it is extremely defensive as corporates do not compromise on cybersecurity just because the economy has turned down a bit.

Years ago, cybersecurity was mostly defined by on-premises, physical firewalls. There was an on-premises network with a physical firewall to protect it. Anybody behind the firewall was considered to be safe. However, with the advent of the internet, email, smartphones, the cloud, work-from-home, work-from-anywhere and the internet-of-things (IoT), the attack surface available to threat actors has grown exponentially. The industry has moved onto a type of zero-trust architecture ([ZTA], a somewhat loose term that many vendors lay claim to), which says that no one is to be trusted, not even a company’s CEO. What if it is not the CEO who has emailed you a request but someone else who has assumed their identity? In my opinion, identity protection is one of the most challenging aspects to get right in cybersecurity.

With the explosion of the attack surface has come a material increase in the suite of products required to protect corporates and individuals. This has left the cybersecurity industry one of the most fragmented in all of tech. There is a long list of individual best-of-breed point solutions and some larger platform companies that offer a suite of products.

The average US corporate uses about 40 different cybersecurity vendors, leading to a complex sprawl of products. This has created a tug-of-war between using best-of-breed point solutions or using a platform whose products integrate into a couple or even a single operating system. I would argue that Palo Alto and Fortinet are the best examples of platform offerings. However, companies like CrowdStrike, Zscaler, and even SentinelOne are all laying claim to platform offerings. Overall, the needle does seem to be shifting to the power of platform offerings.

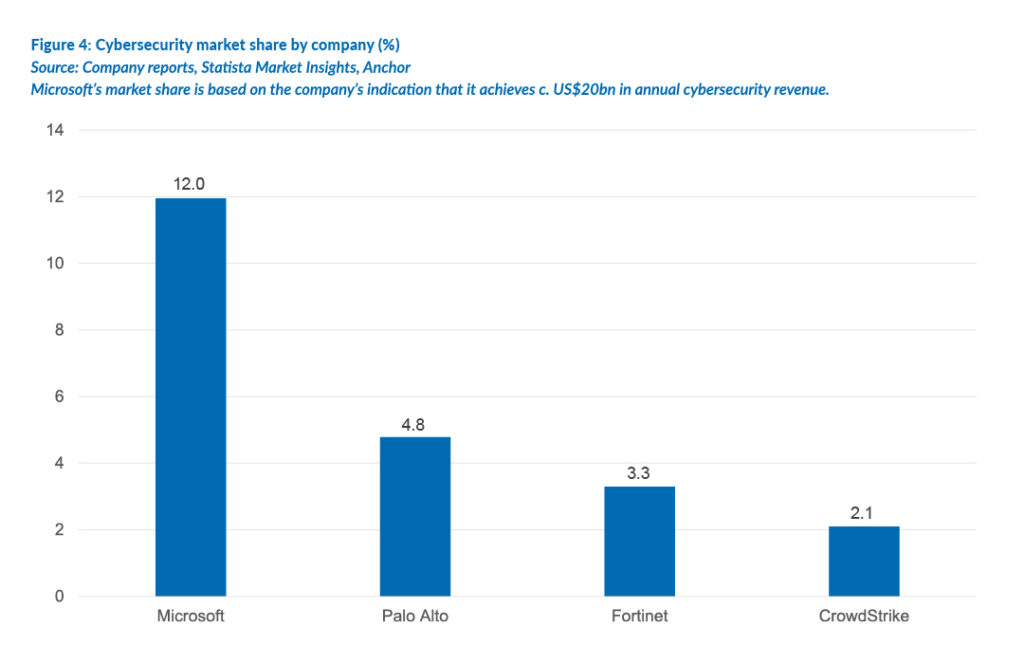

Microsoft is considered the biggest player in the cybersecurity industry. However, it bundles many cybersecurity products into broader software packages. As such, its estimates of c. US$20bn in cybersecurity revenue is often taken with a pinch of salt. It is unclear whether it could achieve this level of revenue if its cybersecurity products were all sold on a standalone basis. There is even some double counting where certain corporates run CrowdStrike or SentinelOne’s endpoint products in conjunction with the Microsoft Defender offering.

Palo Alto is the largest independent cybersecurity company in the world, yet it has only a c. 5% global market share. Fortinet is likely the second-largest independent, with a c. 3% market share.

There is no such thing as the “best” cybersecurity company. Each of the bigger players has strengths and weaknesses. The industry is highly competitive, with many participants adamant that their offerings are the best for each specific purpose. Hence, the clamour for the “best-of-breed” mantle. Corporate buyers do not want to settle for second best when it comes to cybersecurity.

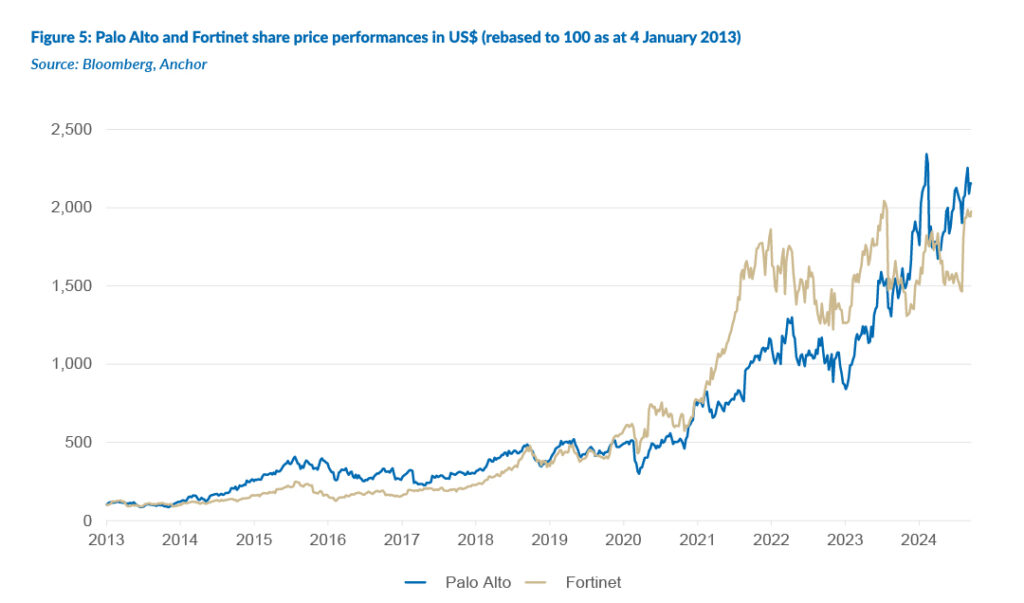

At Anchor, we admire Fortinet as a company, given that it is exceptionally well-run. It has a reasonable P/E for a US growth tech stock, is still run by its founders from c. 20 years ago, highly profitable (its free cash flow cash margin puts it in the top 5%-10% of S&P 500 Index constituents on this measure), a strong balance sheet, a good balance between growth and profitability, a high return on capital employed (as it builds mostly internally with very few acquisitions), and judicious share buybacks typically only when its share price has declined somewhat. As shown in the chart below, Palo Alto and Fortinet have proven to be excellent share investments over time.

There are surveys from Gartner, Forrester and MITRE ATT&CK that attempt to evaluate the companies’ offerings within specific sectors. These surveys are broadly accurate, and undoubtedly, the cream always rises to the top. However, they cannot be blindly relied upon and require some nuance and interpretation. The MITRE ATT&CK evaluation does real-world testing on the various security endpoint offerings in the market. What amuses me is that within 24 hours of the assessment being published, several endpoint vendors publish their interpretation of the results, claiming to have “won”! I have learnt that within this industry, the truth usually lies somewhere in the middle.

The recent explosion of artificial intelligence (AI) is ultimately a tailwind for the cybersecurity sector. Although AI puts more power in the hands of threat actors, it also increases the need for cybersecurity protection. A cybersecurity company like SentinelOne was built from the ground up on AI since 2013, long before AI was fashionable. It is likely to become a case of fighting AI with AI.

Finally, a brief discussion on the recent large-scale IT outage caused by CrowdStrike, one of the world’s leading cybersecurity companies. CrowdStrike is truly a world-class business, which is what makes the outage the company caused even more perplexing. It was not actually a cyber breach but an update/configuration change that rolled out and instantly bricked every Windows machine it touched. It is hard to understand why standard best practise was not employed, such as testing on a few machines first and then incrementally rolling it out in stages. Some in the tech world have questioned whether it points to deeper issues within the company, but we have no way of knowing whether that is true.

Given CrowdStrike’s excellent track record before this incident, we must assume that it is highly unlikely that this exact issue will ever happen to the company again. This will likely slow its signing of new business for the next few quarters, but I am sure that in a couple of years, the world will have mostly forgotten about this incident. Note that cybersecurity contracts typically limit the vendor’s liability to the contract’s value. Without this, the cybersecurity vendors would be open to material litigation on an ongoing basis.

The CrowdStrike incident also highlights the dangers of too much concentration in IT—some diversity between different vendors is not bad. Still, overall, in our view, the ever-growing need for cybersecurity (and the investment thesis for these companies) remains intact as businesses and individuals have to protect their digital assets from increasingly sophisticated cyber-attacks.