This discussion is intended for SA-based investors who have never invested directly in offshore stocks or have only recently started this journey. The broad principles of stock picking are the same anywhere in the world. For example, overpaying for an asset typically leads to bad outcomes everywhere. However, for individuals who have focused their investing primarily in the domestic equity market, starting to buy individual stocks in global markets can be quite daunting and requires a material mind shift, in my experience.

Somewhat tongue-in-cheek, years ago, it felt to me that in SA, we bought shares on a 10x P/E, started to get worried when these shares hit a 15x P/E and sold without asking questions when they hit a 20x P/E. For global investing, especially in the US, it feels like company valuations start at a 20x P/E and work their way up.

The reality is that there are low P/E stocks everywhere in the world, including in the US. There are value managers who can construct global portfolios on low and even single-digit P/Es in aggregate. However, that is quite a unique skill set and requires a very deep analysis of the underlying companies to ensure one is not standing on any proverbial landmines.

Investing in the better-known, mainstream global stocks usually requires paying a P/E multiple that first-time global investors may not feel comfortable with. When I started investing globally years ago, overcoming this “sticker shock” took me a while. After a while, I realised that limiting myself to finding shares trading under a 20x P/E excluded me from many worthwhile investing opportunities.

As a result, I became a lot more open-minded about “optic valuations”. In other words, many global shares I looked at appeared “optically” expensive (e.g., high 12-month forward P/E multiples). Yet, investors had been making excellent returns on some of these shares over many years.

There are multiple reasons why this might be. Most SA companies operate in a very small market by global standards, with limited opportunities to scale internationally. US companies, by comparison, operate in a vast domestic market with material opportunities to scale internationally. By its nature, tech scales quickly across state lines in the US. It also scales quickly across international borders. Unsurprisingly, many of the listed US winners of the past 20 years have come from the tech space, companies like Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, etc., which are global powerhouses today. These same winners have often appeared very expensive but have delivered superior share price performance, high optic valuations notwithstanding. Global investing allows one access to the best management teams in the world, who, in turn, have almost unlimited access to capital.

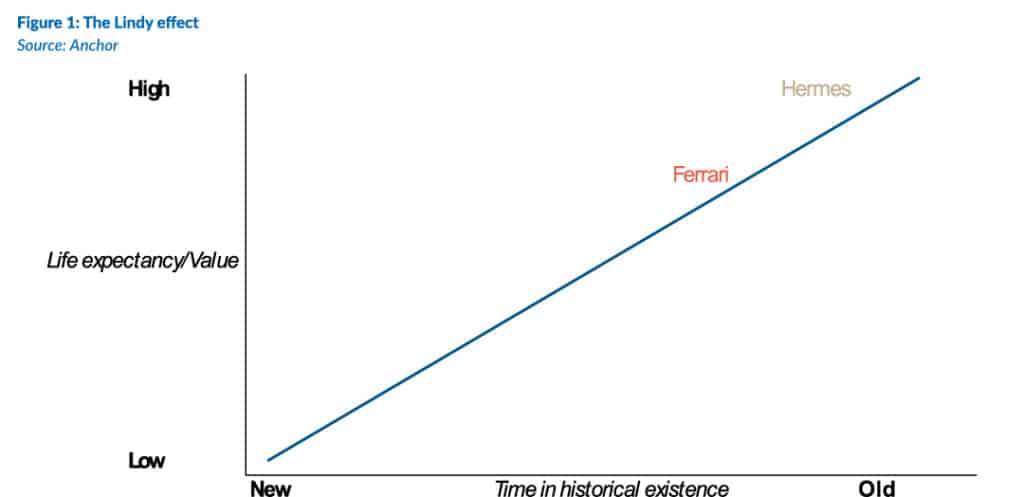

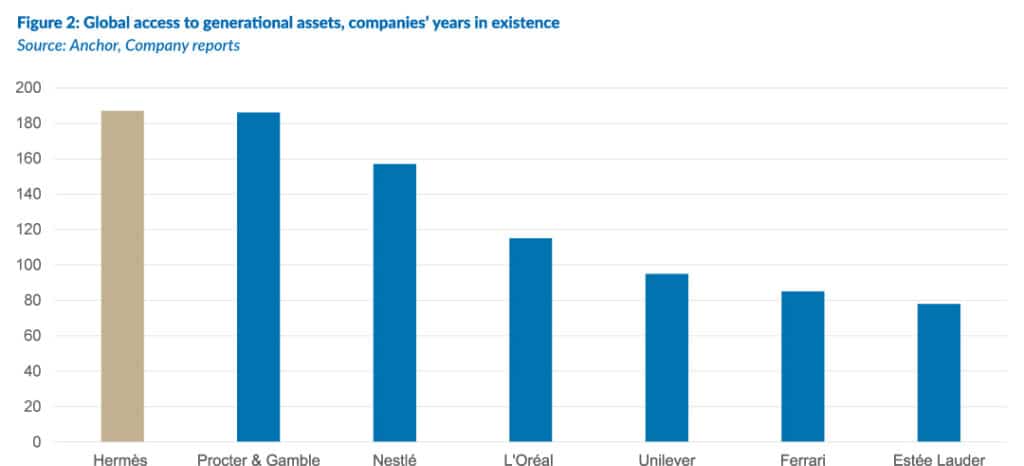

There are also other factors to consider. The Lindy Effect states that the longer something (non-perishable) has existed, the longer it is likely to exist. A company like luxury goods manufacturer Hermès has existed for over 180 years. That means it has survived two world wars, the Cold War, the Great Depression, the global financial crisis (2008-2009) and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020).

No company has a guaranteed future, e.g. personal care product manufacturers such as Revlon and Estée Lauder. However, a company that has survived all the above is unlikely to go bankrupt in the next five years. The issue is that these types of companies do not typically trade on 5x P/E multiples. We simply do not have these kinds of generational companies listed in SA.

Covering SA diversified mining shares on the sell-side for almost 25 years, my analysis was very valuation-driven. My assumption was that most things in cyclical companies revert to the mean over the longer term. However, with global investing, I have found many more secular growth opportunities without apparent means to revert.

I have found far more success in focusing on the individual quality of the businesses I am assessing vs making optic valuations my primary objective. I still view valuation as crucially important. However, I have made evaluating business quality my primary objective, with valuation as a secondary overlay. This approach helps to filter out good businesses that are also overvalued.

In my opinion, a person with a simply brilliant investing mind is Aswath Damodaran, the finance professor at New York University, Stern School of Business. He is otherwise known as the “Dean of Valuation”. He has written several books and delivered countless public talks and lectures on the finer arts of valuing companies. There are arguably few people in the world who know more than he does on how to craft a valuation spreadsheet. Yet, he frequently states how important the narrative is to the investment case of a business. This is especially true for the global powerhouses that have emerged from the US over the past 20 years.

To be clear, I love a good spreadsheet. My whole sell-side career was built on many thousands of lines of spreadsheet data. However, for global investing, I have materially reduced my reliance on spreadsheets as the answer to buying good quality companies. I like the saying that “If all the answers to investing could be found on a spreadsheet, all the world’s Excel junkies would be the richest people on earth.” I am unsure who to credit this saying with, as many seem to have used it in some way.

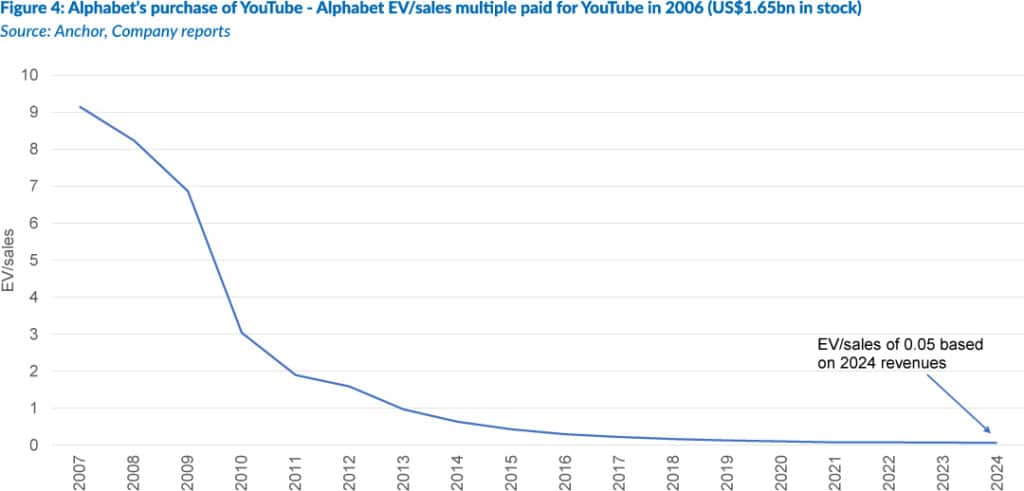

Alphabet bought YouTube for US$1.65bn in 2006, all funded by stock. This is an excellent example of a global asset that appeared optically expensive but was incredibly cheap with the benefit of hindsight. The purchase price looked like a bubble valuation at the time on an EV/sales multiple of 9.2x, and YouTube was loss-making.

However, in 2024, the EV/sales multiple was 0.05x based on the original 2006 purchase price. Alphabet was heavily criticised for buying a “loss-making start-up”. One press article questioned whether Google “swallowed a poison pill they will soon regret”. We should balance this with the fact that Alphabet has made over 250 acquisitions over the years, many of which have failed either partially or entirely. So, it does not always end as well as the YouTube acquisition.

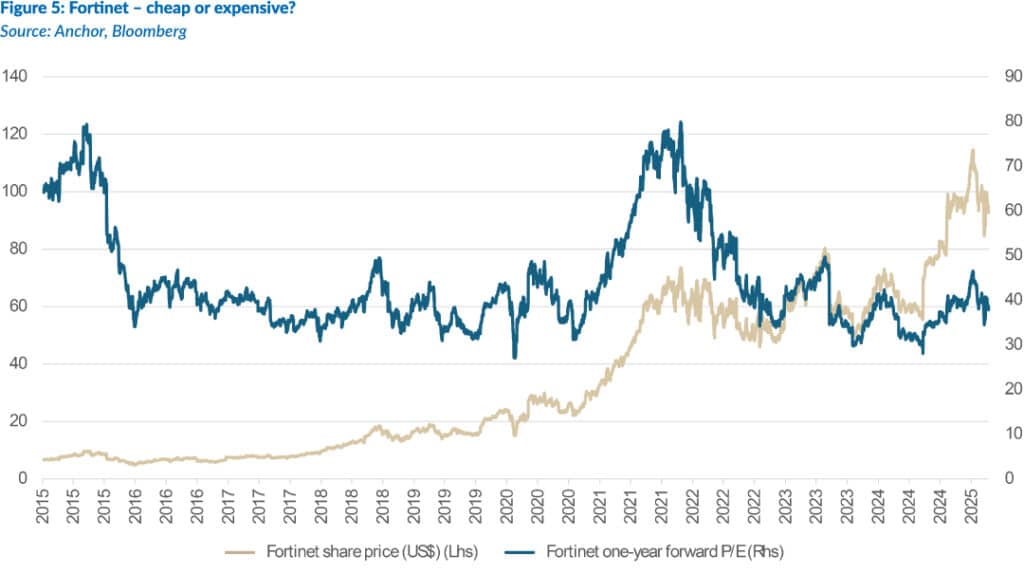

There are so many examples I could give in the US of companies that appeared optically expensive (high, one-year forward P/E multiples) for years but still ended up delivering market-beating returns. One such example is Fortinet. I have followed this stock for years. It is one of the world’s leading cybersecurity companies. It is still run by the founders from about 20 years ago. No single cybersecurity company is the best at everything, and it is a very fragmented industry. However, Fortinet has had a material focus on shareholder returns with high free cash flow (FCF) margins, internal innovation, low stock-based compensation and judiciously timed share buybacks.

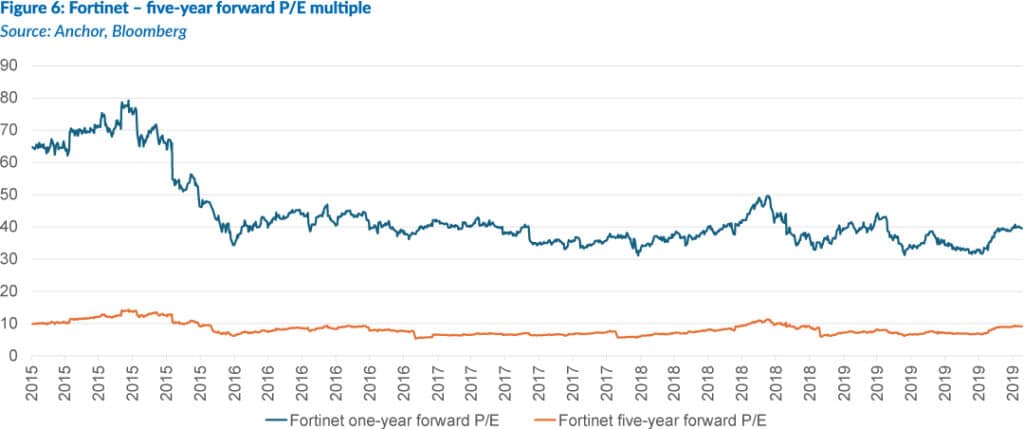

Throughout its listed history, Fortinet has virtually never traded below a one-year forward P/E multiple less than 30x. It has twice touched an 80x forward P/E. Yet the share price has grown about twenty-fold, with 2015 as the starting point in Figure 5 below. A rigid view that any share trading over a 20x P/E is expensive would have kept one out of this fantastic share entirely.

I have tracked Fortinet’s share price in Figure 6 over its five-year forward earnings. This type of exercise can only be done with the benefit of hindsight. This demonstrates that Fortinet has mostly traded on a single-digit forward P/E based on five-year forward earnings. This is not easy to do looking forward. However, it indicates that US fund managers have a good feeling for valuing these longer-dated, high-growth businesses. I believe it pays to keep an open mind when valuing these types of companies.

Another factor that sometimes results in higher valuations, especially for US stocks, is the optionality they offer investors. Optionality does not refer to a restaurant chain being able to open more stores over time. Instead, it refers to the ability of a business to add completely new revenue lines as a function of its current business and installed customer base. This is hard to value as it carries a higher level of uncertainty. However, it can be a robust revenue and earnings driver over time.

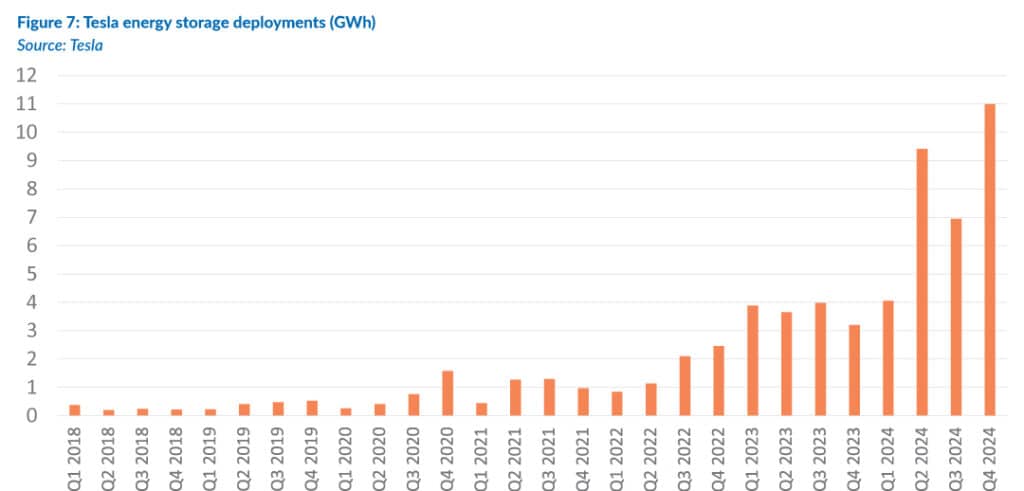

An example of this is Tesla’s energy storage business. This division is too small to be the make-or-break of the Tesla investment case. However, in two-and-a-half years, this business has grown tenfold. During this time, the market focused far more on its mainstream electric vehicle (EV) business.

One of the other lessons I have learnt in global markets is that you bet against the top dog in an industry at your peril. It is tempting to find the number 6 market share player on a low P/E and think it looks attractive. The highest market share player on a high P/E multiple is often the better investment over time. Remember, the biggest player also has the biggest marketing budget, research and development (R&D) team, deepest government relations, etc. The one time this view might not be valid is when a disruptor enters the market.

Another thing I have learned, especially with US tech, is never to underestimate the impact of a powerful marketing team. I used to think that the best tech sold itself and that marketing only needed to be acceptable. However, a powerful marketing team can outsell a competitor’s better-quality tech if that competitor is not at the top of its marketing game.

With global investing, having a large “too-hard” camp is crucially important. There are potentially as many as 50,000 shares listed globally. Even an investment team of several members cannot be on top of all market sectors. For now, many seasoned global fund managers are putting the red-hot AI theme into the “too-hard” camp. Besides the obvious winner of chipmaker Nvidia and the data centres (Amazon, Microsoft and Alphabet), it is difficult to say with certainty who the winners will be. In many respects, it is easier to predict the losers.

The fear of missing out (FOMO) can be overwhelming in global markets relative to the SA market. In SA, it feels like everyone owns the same shares. Even if you miss out on one, chances are it was always staring at you in plain view. Globally, it often feels like you are missing out on all the hot ideas. Resist the temptation to start throwing darts at every hot idea your friends all seem to own.

Global markets, especially the US, are more susceptible to bubbles than we are used to in SA. Bubbles in individual stocks. Bubbles in sub-sectors and bubbles in overall sectors. You want to avoid those at all costs. It feels like the last time we had a clear bubble in the domestic equity market was around the time of the global tech bubble in 1999-2000.

If many/most US-based investors lack an information edge despite living in the US, what edge could we have living outside that region? The expression “you don’t know what you don’t know” is especially true for investors venturing outside their home market for the first time. The one critical edge you can have, no matter where you live, is investing temperament. Taking a patient and long-term view of the quality stocks in your global portfolio can more than offset any short-term information edge you might lack.

In my view, no one can reliably predict market crashes. The whole reason a market crashes suddenly is that something happens that absolutely no one expected. However, there is no doubt that US markets and many high-quality global companies, in general, are expensive by their historical standards. We can say with reasonable conviction that the returns for US stocks over the next 15 years will likely lag the outstanding returns we have enjoyed over the past 15 years. Finally, global investing is not necessarily about achieving higher returns. It is more about geographic diversification and access to an enormous pool of investment opportunities across diverse industries. Along the way, it can also be a lot of fun!