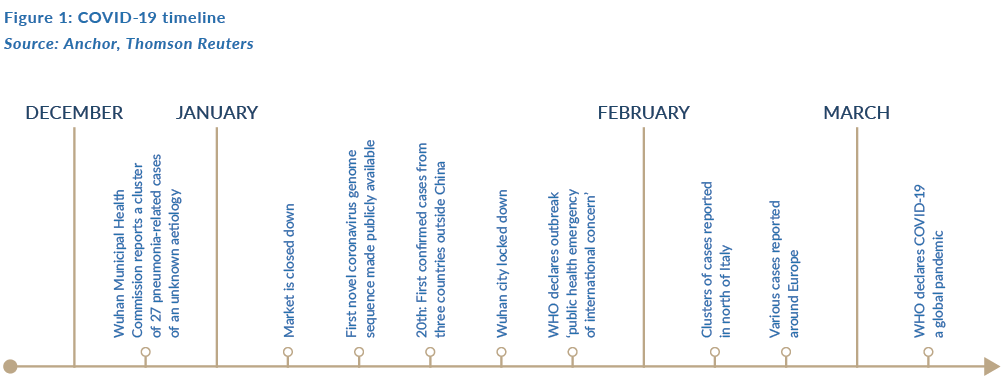

On 31 December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission in Wuhan City, China, reported a cluster of 27 pneumonia-related cases of an unknown aetiology, with a reportedly common link to Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. Twenty days later, there were reports of confirmed cases from three countries outside China: Thailand, Japan and South Korea, with the cases all having been exported from China. On 22 February, Italian authorities reported clusters of cases in Lombardy and additional cases from two other regions, Piedmont and Veneto. Over the following days, cases were reported from several other regions. Transmission appeared to have occurred locally, in contrast to first-generation transmission from people returning from affected areas in other countries.

As a further cause of concern, transmission events were also reported from hospitals, with COVID-19 cases identified among healthcare workers and patients. During the following week, several European countries reported cases of COVID-19 in travellers from the affected areas in Italy, as well as cases without epidemiological links to Italy, China or other countries with ongoing transmission cases. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak a ‘public health emergency of international concern’. In the weeks to follow, several countries implemented entry screening measures for arriving passengers from heavily effected areas, along with major airlines suspending flights from said areas. As cases continued to mount, hard-hit countries (particularly within Asia and Europe) began to install strict public health initiatives, including social distancing measures that led to the closure of many public entertainment spaces. On 11 March, less than a month and a half from the first reported cases, the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic due to a rapid exponential increase in cases.

As policymakers around the world struggle to combat the rapidly escalating pandemic, they find themselves in uncharted territory. Much has been written about the measures and policies successfully used in countries such as China, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan to curb the spread of the virus but, unfortunately, throughout much of Europe and the US, it is already too late to contain COVID-19 in its infancy.

As a consequence, policymakers are struggling to keep up with the spreading pandemic and, in doing so, are repeating many of the early errors made in Italy, where the pandemic has since turned into a humanitarian disaster. Some aspects of this pandemic — starting with its timing — can undoubtedly be attributed to plain ‘sfortuna’ (or bad luck in Italian), that were impossible for policymakers to fully control. Other aspects, however, are symbolic of the profound obstacles that leaders in Italy (as well as elsewhere in Europe and now possibly the US) faced in recognising the magnitude of the threat posed by COVID-19, and thus organising a systematic response to it and learning from early implementation successes (or more importantly, failures).

It is, however, worth noting that these obstacles emerged even after COVID-19 had fully taken hold in China, and some alternative models for the containment of the virus (in China and elsewhere) had already been successfully implemented. What this suggests rather is a systematic failure to both absorb and to act upon existing information rapidly and effectively, rather than a complete lack of knowledge of what ought to be done.

The spread of COVID-19 is having a profound and extensive impact on the global economy and has sent policymakers into a relative frenzy looking for effective ways to respond. China’s experience thus far shows that the right policies make all the difference in fighting the disease and mitigating its impact — but some of these policies come with difficult economic trade-offs. Unfortunately, success in containing the virus comes at the price of slowing economic activity, no matter whether social distancing and restricted movement are voluntary or enforced. In China’s case, policymakers implemented strict mobility constraints, both at a national and local level. Whilst the human cost of the pandemic is clearly apparent, the economic costs are yet to be fully understood. By all indications, China’s slowdown in 1Q20 will add significant downward pressure on economic growth and will leave a deep mark for the remainder of this year.

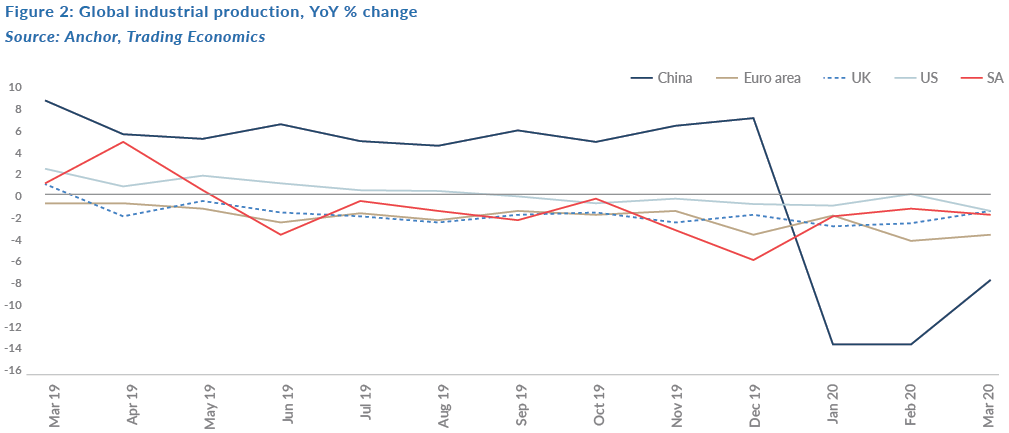

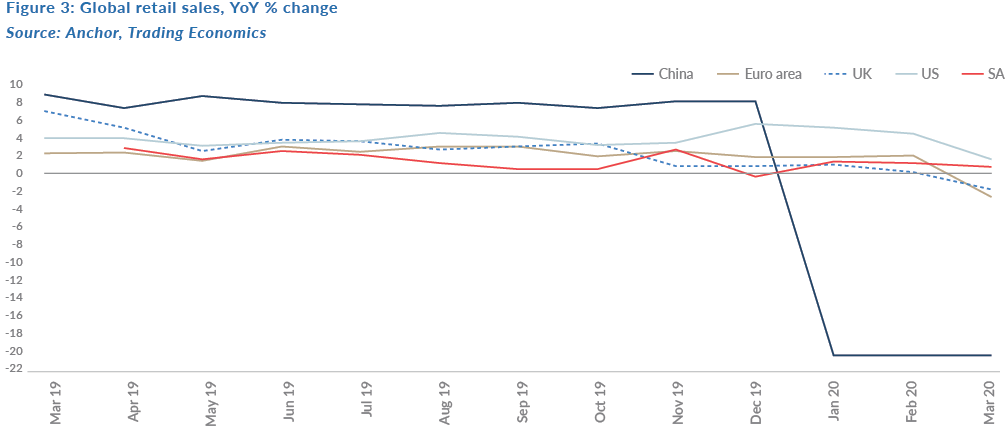

What started as a series of sudden stops or ‘blips’ in economic activity, quickly cascaded through the global economy and morphed into a full-blown shock, simultaneously impeding supply and demand. This is clearly visible by the very weak January-February (and preliminary March) readings of industrial production and retail sales across the globe. The novel coronavirus shock is severe, even compared to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007/2008, as it has hit households, businesses, financial institutions, and markets all at the same time—first in China and now globally.

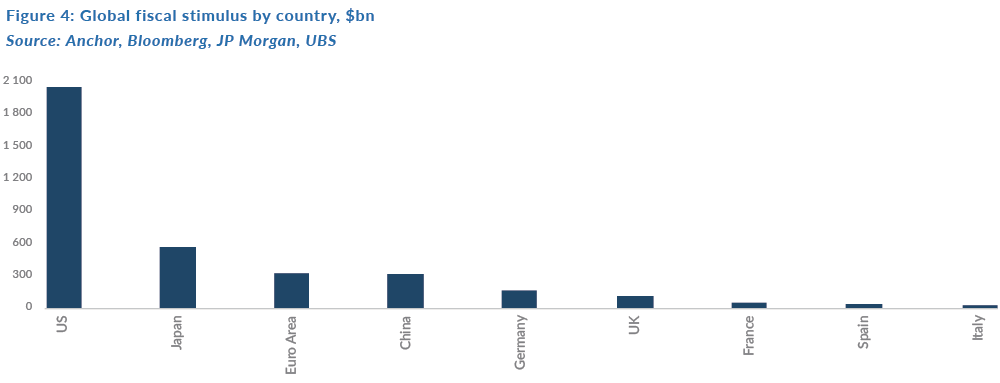

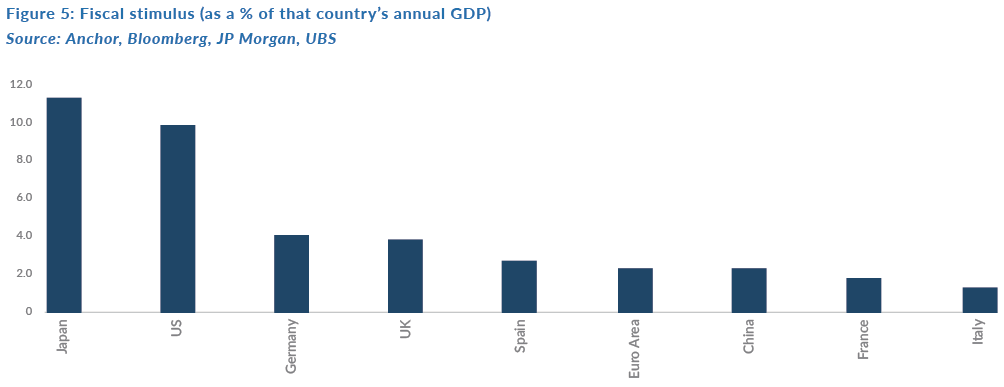

Mitigating the impact of this severe shock requires providing support to the most vulnerable. Chinese policymakers have implemented an estimated RMB1.3trn (c. $183bn or 1.2% of China’s GDP) of fiscal measures to mitigate the economic impact of the virus. Some of these key measures include: (i) increased spending on epidemic prevention and control; (ii) production of medical equipment; (iii) the accelerated disbursement of unemployment insurance; and (iv) tax relief and waived social security contributions. The overall fiscal expansion is expected to be significantly higher, reflecting the effect of already announced additional measures (including higher infrastructure investment). The People’s Bank of China (PBC) has further unleashed a swathe of monetary policy support, in addition to the government’s provision of financial relief to affected households, corporates, and regions facing repayment difficulties.

Due to the rapid spread of the virus across Europe, the euro area has released a swathe of fiscal stimulus in a bid to alleviate the economic damage wrought by the virus across the continent. By end-March, fiscally, the EU had implemented a total of c. $315bn/2.3% of EU-27 (those EU countries after the UK left the EU) GDP worth of measures that aim to support public investment or hospitals, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), labour markets, and stressed regions.

Notably, the European Commission also activated the general escape clause in EU fiscal rules, which suspends fiscal adjustment requirements for countries not at their medium-term objective and allows countries to run deficits in excess of 3% of GDP. However, EU member nations continue to disagree over deploying a joint fiscal stimulus. Time will tell if the various stakeholders will deploy the necessary expansionary fiscal policy needed to assist the EU through this period of extreme volatility.

SA was quick to take its cue from other countries that have stringent measures in place to curtail the spread of the virus. The government has declared a national state of disaster and adopted various containment measures, accumulating in a nationwide lockdown from midnight, 26 March until 16 April, with only critical workers, transport services, essential food and medicine production and retail operating. In order to mitigate the economic fallout from such strict containment measures, government will assist companies facing distress through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and special programmes from the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

Funds will be made available to assist SMEs under stress, mainly in the tourism and hospitality sectors. Allocations will also be made to a solidarity fund to help combat the spread of the virus, which will be created with the assistance of private contributions. On the tax front, revenue administration will accelerate reimbursements and tax credits and allow SMEs to defer certain tax liabilities. The authorities have released partial cost estimates for the measures, so far amounting to R12bn (0.2% of GDP). The government is working on additional support measures to be presented to Parliament. Monetary wise, the SARB has cut interest rates and implemented various support measures that essentially amount to a form of quantitative easing (QE).

In comparison, the US has run a disjointed, delayed and, at times, contradictory response to the implementation of containment measures against the outbreak. Under the leadership of President Donald Trump, the federal government has often been at loggerheads with various state leaders and the country’s own medical experts surrounding what is deemed to be the appropriate level of containment response. Economically speaking, the US was more robust than most other DM economies before the crisis and thus has been able to ease policy more. There is, however, a catch-22 to this monetary easing – whatever US interest advantage was in place before the crisis has now been whittled away as the Fed has taken rates back to near zero. As the US is also closer to its Presidential election than most, it is a natural assumption that electoral factors will drive policy response to the pandemic. In particular, the possible rush to get the US economy back to work as recently touted by Trump could easily backfire if it takes the country longer to get on top of the outbreak. Fiscally, the US has released a swathe of measures, including a $2trn stimulus package to soften the blow of the crisis on the economy.

Despite much economic uncertainty, what is clear at least is that safeguarding financial stability requires assertive and well-communicated action. The past weeks have shown how a health crisis, however temporary, can turn into an economic shock where liquidity shortages and market disruptions can intensify and act as a catalyst to a far greater economic downturn. Of course, some of the fiscal and monetary relief tools come with their own set of problems. For example, allowing a broad range of debtors more time to meet their financial obligations can undermine financial soundness later on if it is not correctly aimed at the problem at hand and is time-limited; subsidised credit can be misallocated; and keeping already struggling companies alive could hold back productivity growth later. Evidently, wherever possible, using well-targeted and time-conscious instruments are key.

While there are reassuring signs of economic normalisation in China, significant risks remain. This includes new infections rising again as national and international travel resumes. As more countries face rapidly increasing spread of the virus and global financial markets continue to twirl downwards, consumers and firms may remain wary, depressing global demand for Chinese goods just as the economy is getting back to work. Given the global nature of the COVID-10 outbreak, many of these efforts will be most effective if coordinated internationally.

Since the start of the outbreak, economists and strategists alike are coming out with forecasts for economic growth, earnings, and asset prices. These forecasts tend to range wildly on any of these measures. In reality, all of the measures forecast depend heavily on how long both local economies and by large, the global economy, will stay shut down in response to the pandemic (e.g. estimates range from weeks to months or even quarters). The time that various economies across the globe are ‘re-started’ depends on the dynamic of the virus itself and the choices politicians and society make in the process. Thus, the likely effect of COVID-19 on the global economy – with its countless international linkages and multiplier effects – is impossible to quantify with any degree of certainty.

Nevertheless, in responding to any crisis such as a virus pandemic or similarly, a threat of war, there is a trade-off which society needs to make. At the extremes, society can: 1) underreact – leading to the catastrophic impact of a pandemic or being unprepared for a military aggression: 2) overreact – and in the process cripple the economy/society or provoke an unnecessary war: or 3) decide on an optimal response, that stops the crisis, while incurring calculated damage which is significantly smaller than in the other two extreme outcomes. The foremost risk in both overreacting and underreacting to the current crisis is devastating damage to the economy. Subsequently, the natural question for policymakers across the globe is: How should one come to an optimal response in the case of the current epidemic? One needs to have as much epidemiological data as possible available on the virus itself, real-time dynamic data of its spread, effectiveness of measures already taken, and risks and unintended negative consequences of measures taken. More often than not, the response evolves initially from underreaction, then overreaction and then converges closer to the optimal response required.