The recent rise in Japanese government bond (JGB) yields and yen weakness has reignited concerns about a potential fiscal crisis. In our view, these fears are misplaced, and we do not believe the government will struggle to get financing. Japan’s fiscal position is often judged by the size of its debt alone, but this only provides a partial picture. At first glance, the situation may appear concerning; however, a closer look at the underlying dynamics is more reassuring. On balance, we favour long-dated JGBs and are bullish on the yen.

The recent sell-off in JGBs is not, in our view, a sign of a brewing fiscal crisis. Rather, yields have moved higher as Japan has emerged from years of deflation, and the policy mix is clashing. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is tightening monetary policy just as Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s government shifts towards fiscal expansion. This policy divergence has unsettled markets and raised uncertainty about how far rates may ultimately need to rise (the policy rate is currently at 0.75%). The yen weakness reflects the BoJ’s hesitance to tighten aggressively.

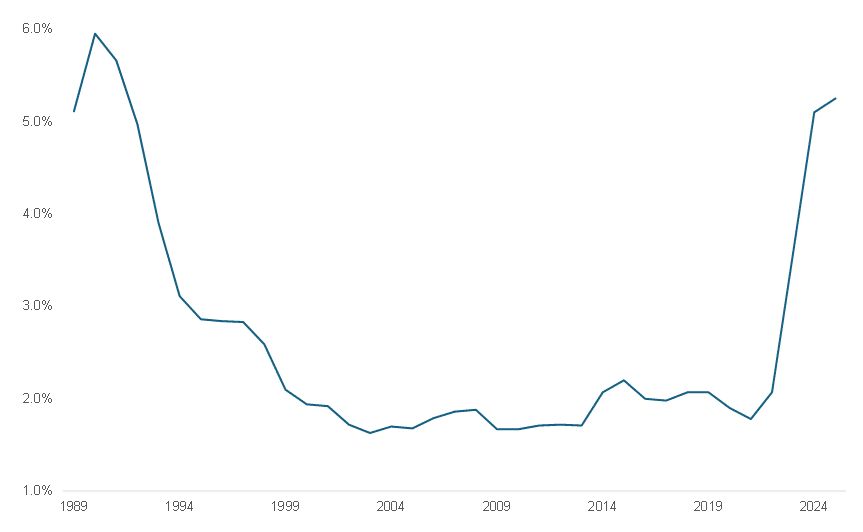

Figure 1: Wage negotiations, YoY change

Source: Anchor Capital, RENGO

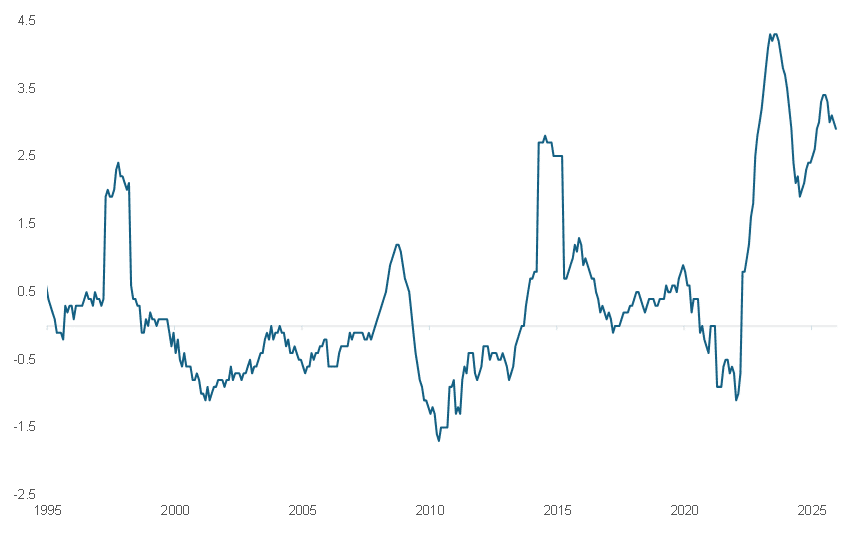

Figure 2: Japan core CPI, YoY % change

Source: Anchor Capital, Thomson Reuters

Strong wage growth suggests that Japan has finally broken out of the deflationary trap that weighed on the economy for decades. Annual wage negotiations have exceeded 5% for two consecutive years, and the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (RENGO), the country’s largest trade union, is targeting another 5% increase this year (Figure 1). Economy-wide wages are rising by around 4% YoY, while core inflation is running at about 3%, well ahead of the BoJ’s 2% target (Figure 2). In the past, Japan has experienced temporary bursts of higher inflation, but these episodes proved short-lived because wage growth remained subdued. This time, however, stronger and more sustained wage gains suggest that inflation could prove more persistent than in previous cycles. We are, however, closely monitoring consumption trends, which are probably influencing the prime minister’s push for easing fiscal policy. Real private consumption as a percentage of GDP is declining.

Takaichi’s decision to call a snap election less than halfway through the legislative term proved highly successful, with the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP) securing 316 of 465 seats and a clear mandate to implement its agenda. She has signalled a shift away from what she sees as an excessively tight fiscal stance, favouring a more proactive approach to supporting growth and boosting household demand. Key proposals include a temporary two-year removal of VAT on food, higher defence spending, and greater investment in strategic sectors such as AI and semiconductors. Early estimates suggest these measures could loosen fiscal policy by around 1.0%–1.5% of GDP

We do not believe this modest easing in fiscal policy is likely to trigger a fiscal crisis. Fiscal sustainability in Japan cannot be assessed in isolation from the private sector balance sheet.

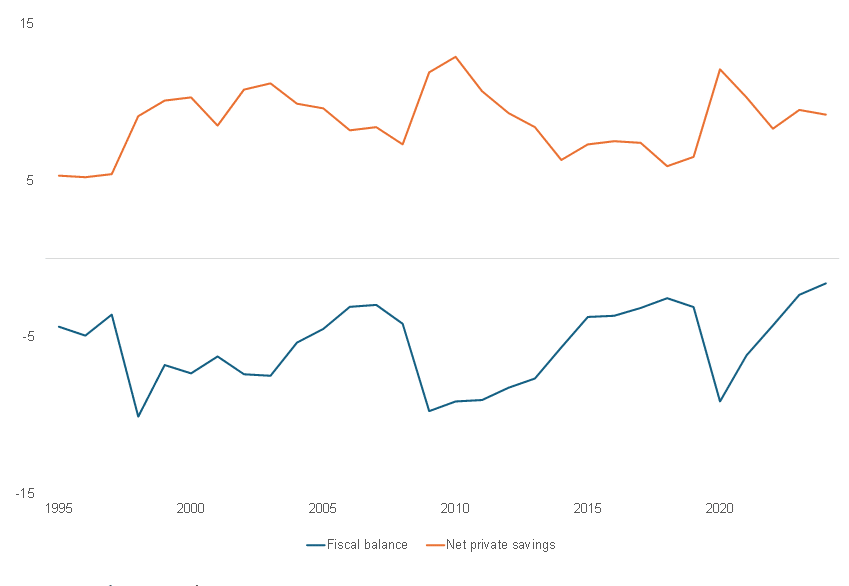

Figure 3: Fiscal balance and net private savings, % of GDP

Source: Anchor Capital, IMF

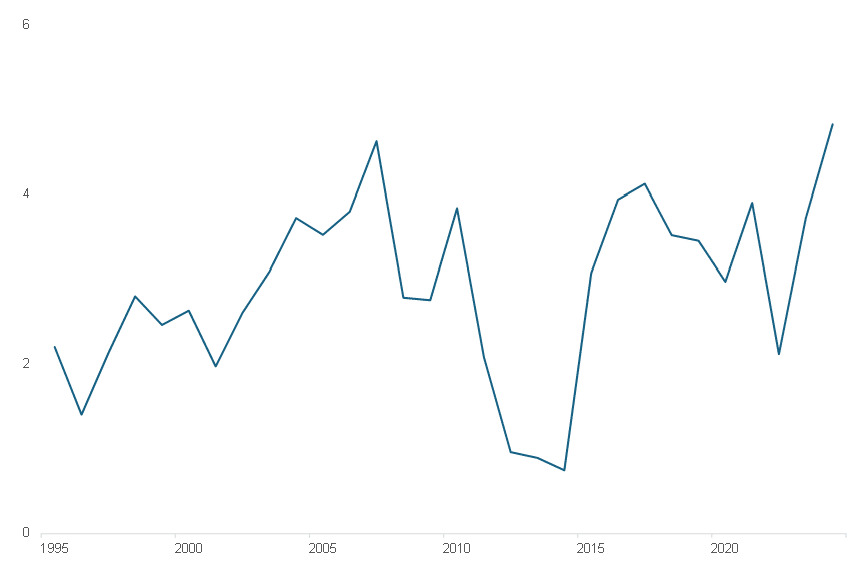

Japan continues to have high levels of domestic private sector savings (Figure 3). The balance sheet recession that followed the collapse of the asset bubble in the early 1990s created a lasting preference among households and companies to save. Corporate deleveraging through the mid-1990s turned firms into net savers, leading to a persistent private-sector surplus. As a result, net private sector savings comfortably exceed the fiscal deficit (Figure 3). In other words, the domestic private sector generates enough savings not only to finance the government’s borrowing but also to invest abroad, including in markets such as the US and Europe. This dynamic is reflected in Japan’s large and persistent current account surplus (Figure 4). As long as these conditions persist, the Japanese government is unlikely to face difficulty securing financing.

Figure 4: Current account balance as % of GDP

Source: Anchor Capital, IMF

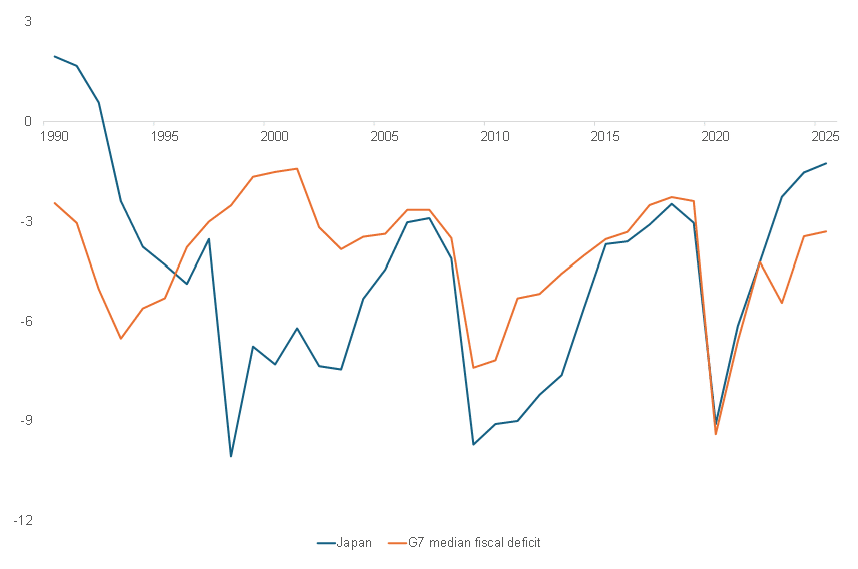

Zooming in on the fiscal position, and starting with the interest burden, Japan’s fiscal deficit is currently narrowing and is projected to narrow further this year (Figure 3). This shows lower funding requirements. Relative to other developed markets, Japan is in a much better position to ease fiscal policy if needed. Its fiscal deficit is smaller than that of many other G7 countries (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Japan fiscal deficit (as a % of GDP) vs the G7

Source: Anchor Capital, IMF

The role of the BoJ is very important when evaluating the interest burden. After years of yield curve control (YCC) and quantitative easing (QE), the BoJ now holds more than half of the government’s outstanding debt. A significant portion of the interest paid (coupon payments) on these bonds held by the BoJ is ultimately returned to the Japanese government each fiscal year. In other words, interest paid on BoJ-held bonds is largely recycled back to the government, materially reducing the government’s effective interest burden, which is even lower than it appears on the surface.

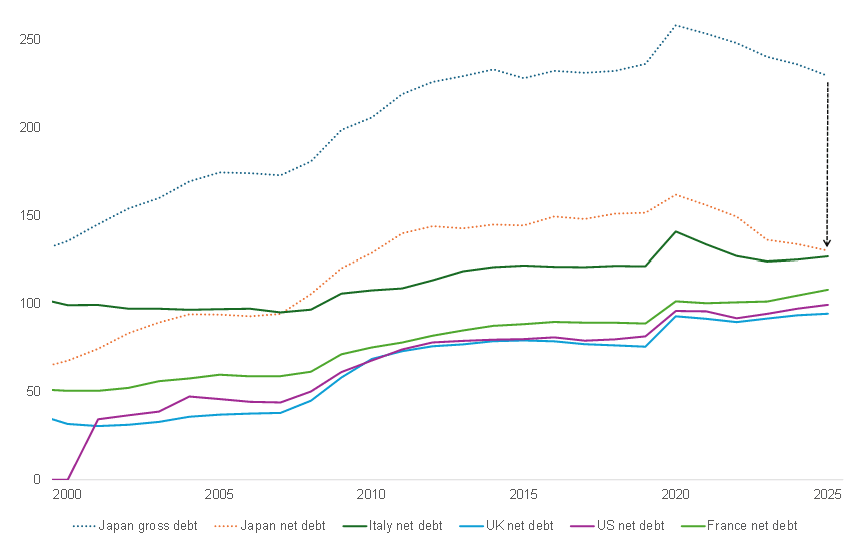

Turning to the debt burden, much like the interest burden, Japan’s debt load is more manageable than headline figures suggest. Before zooming in, it is worth noting that the debt is inflating away. While Japan’s gross public debt remains high at around 230% of GDP, this has declined from roughly 260% five years ago (Figure 6). It is critical to assess a country’s debt net of its financial assets, rather than rely solely on gross figures when evaluating the debt burden.

Japan holds substantial financial assets, including foreign exchange (FX) reserves of c. US$1.4trn, equivalent to roughly 35% of GDP. After accounting for these and other financial assets, Japan’s net debt falls to around 130% of GDP (Figure 6) – comparable to other advanced economies such as Italy, France, the UK, and the US (Figure 6). We draw further comfort from the fact that a significant share of government bonds is also held by the BoJ and other public sector entities, including the government pension fund – the largest in the world -which are unlikely to be forced sellers. Once these holdings are considered, the effective debt burden is even lower than it appears on the surface.

Figure 6: Japan debt burden (as a % of GDP) vs other advanced economies

Source: Anchor Capital, IMF

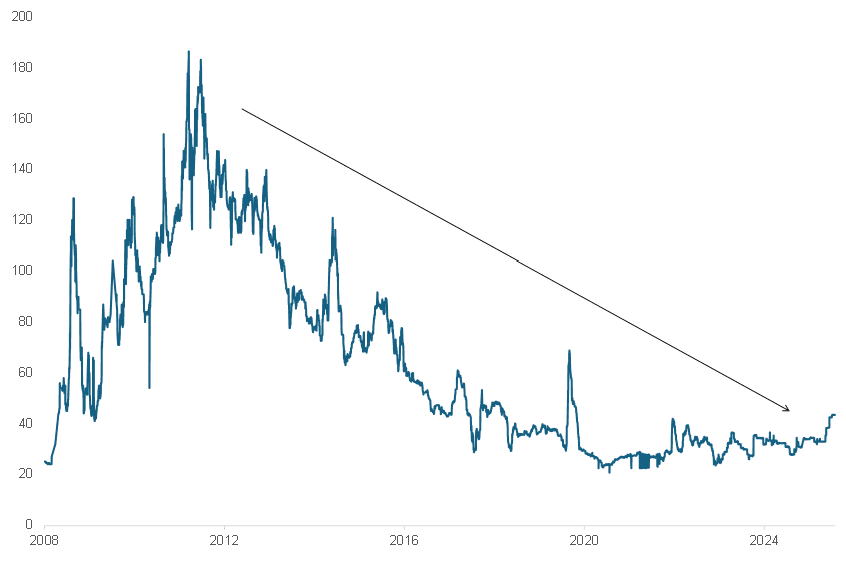

At its core, a modest easing in fiscal policy is unlikely to trigger a debt crisis. Japan’s effective interest burden remains low, and the debt burden is more manageable than headline figures suggest. This combination of low interest burden and a lighter effective debt burden helps keep default risk low. This is reflected in Japan’s tight credit default swap (CDS) spreads—the premium investors pay to insure against a default on Japanese government debt (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Japan 10-year CDS spread, bps

Source: Anchor Capital, Thomson Reuters

If Takaichi follows through with plans to ease fiscal policy, the BoJ may need to normalise policy more quickly. In our view, the BoJ is behind the curve, which has contributed to yen weakness. The neutral policy rate (the level at which the policy rate is neither stimulative nor restrictive) is estimated at 1.0%–2.5%. With the policy rate at 0.75%, the BoJ is 100 bps to the midpoint of the range, suggesting there is still some distance to cover, particularly with inflation around 3%.

Fiscal easing alongside faster monetary tightening would likely reprice front-end JGB yields higher while supporting the back-end yields. This policy mix should also support the yen, which still appears undervalued, especially as yield differentials with the US and the euro area continue to narrow. Against this backdrop, we favour longer-dated JGBs and remain constructive on the yen against both the US dollar and the euro.